Antoine Galland

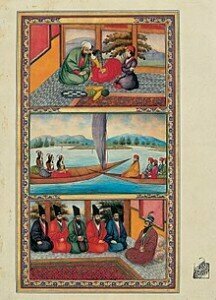

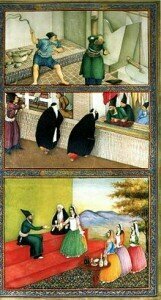

It tells the story of the murderous ruler Shahryar, who finds out that his first wife had been unfaithful, so he decided to marry a new virgin each day, and has them beheaded in the morning. Eventually the vizier, whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees.

It tells the story of the murderous ruler Shahryar, who finds out that his first wife had been unfaithful, so he decided to marry a new virgin each day, and has them beheaded in the morning. Eventually the vizier, whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, Op. 35

Scheherazade is commonly described as “pleasant and polite, wise and witty, well read and well bred. She has perused the books, annals and legends of preceding Kings, and the stories, examples and instances of bygone men and things; indeed it was said that she had collected a thousand books of histories relating to antique races and departed rulers. She had perused the works of the poets and knew them by heart; she had studied philosophy and the sciences, arts and accomplishments.” In the framing tale, Scheherazade volunteers to spend one night with the king, and she begins to tell her first story. The king listens in awe, and as morning dawns, Scheherazade stops in the middle of the story, promising to finish the tale the next night. She finishes the story the following night, but begins a second, even more exciting tale, which she again stops halfway through. At the end of 1,001 night, and 1,000 stories, Scheherazade has no more tales to tell. However, the king has now fallen in love with her, and makes her his queen.

Scheherazade is commonly described as “pleasant and polite, wise and witty, well read and well bred. She has perused the books, annals and legends of preceding Kings, and the stories, examples and instances of bygone men and things; indeed it was said that she had collected a thousand books of histories relating to antique races and departed rulers. She had perused the works of the poets and knew them by heart; she had studied philosophy and the sciences, arts and accomplishments.” In the framing tale, Scheherazade volunteers to spend one night with the king, and she begins to tell her first story. The king listens in awe, and as morning dawns, Scheherazade stops in the middle of the story, promising to finish the tale the next night. She finishes the story the following night, but begins a second, even more exciting tale, which she again stops halfway through. At the end of 1,001 night, and 1,000 stories, Scheherazade has no more tales to tell. However, the king has now fallen in love with her, and makes her his queen. Jozef Kapustka: Lullaby for Little Scheherazade

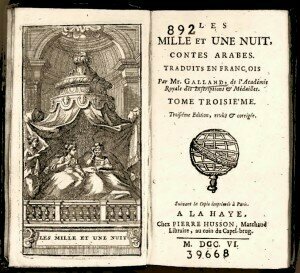

The French orientalist and archaeologist Antoine Galland (1646-1715), most famously, made the first European translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” titled “Les mille et une nuits.” His version of the tales appeared in twelve volumes between 1704 and 1717, and exerted significant influence on European literature and music. This collection included stories that were not in the original Arabic manuscript, including the popular “Aladdin’s Lamp,” “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” and “The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor,” among others.

The French orientalist and archaeologist Antoine Galland (1646-1715), most famously, made the first European translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” titled “Les mille et une nuits.” His version of the tales appeared in twelve volumes between 1704 and 1717, and exerted significant influence on European literature and music. This collection included stories that were not in the original Arabic manuscript, including the popular “Aladdin’s Lamp,” “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” and “The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor,” among others.

Fazil Say: Violin Concerto, “1001 Nights in the Harem”

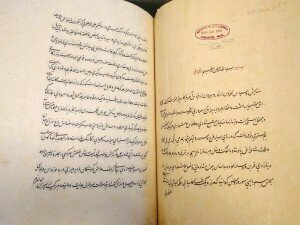

Persian Manuscript of 1001 Nights

Carl Maria von Weber: Abu Hassan, “Overture”