Robert Schumann, 1850

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) suffered from various mental illnesses from an early age. Counselors and historian suggest that his diagnosis was dementia praecox, an illness soon renamed schizophrenia. Beginning in 1849, Schumann began to suffer from auditory hallucinations, and he heard music constantly playing in his head. In addition, he was afflicted by visual hallucinations, and typically saw angelic beings or scenes. Schumann even claimed to have composed works that were played to him by angels. Eventually, he started to see demons and told his wife Clara that he was worried about hurting her.

Friedrich Hebbel

The onset of these serious symptoms coincided with one of the most intensely creative period in his life. Faced with a growing shadow of insanity and death, Schumann collected the last of his creative energies and composed works of unimagined poetic depth. Setting four duets to poems by Rückert, Kerner, Goethe, and Hebbel in his Op. 78, Schumann masterfully develops a distinct sense of the dramatic. In Hebbel’s “Lullaby for a sick child,” the heightened sense of emotionality and physically felt helplessness directly informs the musical setting.

Robert Schumann: 4 Duette, Op. 78 – No. 4 Wiegenlied (Mitsuko Shirai, soprano; Josef Protschka, tenor; Norman Shetler, piano)

Peter Cornelius

Christian Friedrich Hebbel solemnly declared, “All art is based in deepest earnest.” The composer Peter Cornelius (1824-1874) wasn’t entirely convinced and wrote, “My art sets out to be cheerful, simple, exhilarating sensation, based on the popular idiom, rooted in convention, not in vain, sensual love that is concerned only with the egocentric that denies God.” Only a few of his song settings were published during his lifetime, but that was clearly not a judgment on their quality, “as the high ambitions with which these unpublished songs were imbued would have hindered a ready sale. High ambitions seemingly played a subordinate role in his delightful setting of Hebbel’s poem “To a sleeping child.”

When, my little one, I stand before you,

When I see you smile in your dream,

When you glow so wonderfully,

Then, I wonder with sweet dismay:

If I were allowed to look into your dreams,

Would everything, be so clear to me?

The world is still a mystery to you,

You have yet enjoyed no desire,

No, only joy is what you feel.

How do you dream so sweetly then,

If not still you in that place,

From where you came, so suddenly?

Peter Cornelius: 6 Lieder, Op. 5 – No. 2 Auf ein schlummerndes Kind (Markus Schäfer, tenor; Matthias Veit, piano)

Alban Berg © Max Fenichel

The early songs by Alban Berg (1885-1935) take their stylistic bearings from a variety of sources. Between 1901 and 1902, his songs show the influence of Schubert, Schumann, Wagner and Mahler. Subsequently, Berg experimented with chromaticism and enharmonic procedures in the manner of Richard Strauss and Hugo Wolf. Beginning in 1904, however, Berg adopted a new approach to his compositions that added “consistency of the piano part and the handling of his thematic material with more counterpoint and rhythmic variation.” The influence of Johannes Brahms is ever-present, but with his Four Songs Op. 2, Berg gradually transcended tonality. Already the first song, on a text by Hebbel from his collection of poems entitled “Moments of Life,” reveals a wider concept of tonality.

To sleep, to sleep, nothing but to sleep!

No awaking, no dream!

Of those sorrows that I suffered,

hardly the faintest recollection.

So that I, when the fullness of life

reverberates into my rest,

I will only cover myself even more deeply,

and more tightly close my eyes!

Alban Berg: 4 Lieder, Op. 2, No. 1 Schlafen, schlafen, nichts als schlafen (Mitsuko Shirai, mezzo-soprano; Hartmut Höll, piano)

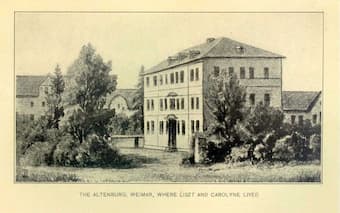

Altenburg, Weimar

Although world-famous pianist Franz Liszt and the son of a bricklayer Friedrich Hebbel had comparatively little in common, they still were friends from about 1858 until 1861. Liszt had set up residence in the Villa Altenburg and Hebbel, who had achieved fame for his tragedies of common life, was overseeing the premiere of his “Nibelungen Trilogy” at the Weimar theatre. Their unlikely friendship found a fruitful dialogue between literature and music in the short poem “Flower and Fragrance.”

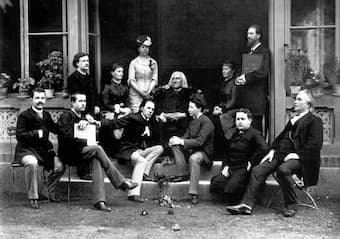

Liszt and his students

If, in sacred spring,

Some fragrances moves you deeply,

Don’t look for the flower

From which the breath emanated.

Fragrance intimates eternity,

Life whose limits can’t be surveyed;

The flower just reminds us of

How quickly it will fade.

Liszt produced two different musical versions, but both emphasize the contrast between body and soul. In literature as in music, fragrance becomes the sound that slowly fades into eternity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Blume und Duft, S324/616 (Mitsuko Shirai, mezzo-soprano; Hartmut Höll, piano)