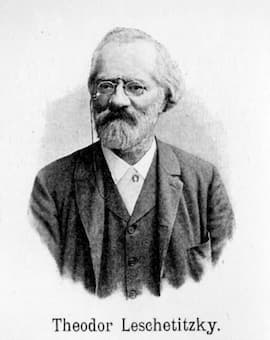

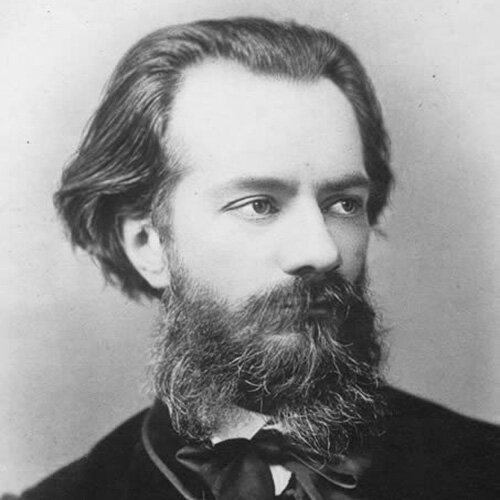

Theodor Leschetizky, 1911

Theodor Leschetizky’s career as a pedagogue spanned the better part of 75 years. In all, in excess of 1,200 students are known to have studied with him. The sheer number of students is of course striking, but more impressive is the quality of artistry demonstrated by his students. Leschetizky and his assistants did not produce countless carbon copies, but taught a group of exceptional artists with completely different approaches to pianism. They decisively influenced pianism throughout the twentieth century, and they will continue to inspire countless generations of new and aspiring pianists in the 21st century as well. Leschetizky was keenly aware of his influence and significance as a pedagogue, as he once remarked, “People forget the artists who have only played, but pupils carry on the teacher’s memory.” It would be impossible to pay tribute to each great pianist who emerged from the Leschetizky studio; as such, let’s focus on a few representative pianists who carried on the Leschetizky legacy.

Theodor Leschetizky: Souvenirs d’Italie, Op. 39, No. 1 Barcarola (Venice) (Theodor Leschetizky, piano)

Artur Schnabel, 1906

We certainly must count Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) amongst the most influential pianist and pedagogues in the 20th century. He had moved to Vienna with his family at a young age and became a Leschetizky student. Schnabel, contrary to the fashion of his time, abhorred empty displays of bravura and virtuosity. He always was an introvert, looking for an intellectual approach to music. Leschetizky instinctively understood the depth of Schnabel’s character by telling his young charge, “you will never be a pianist; you are a musician.” Instead of assigning him the huge romantic warhorses, the focus turned to Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven. It is hardly surprising that Schnabel became one of the premier interpreters of Beethoven, and he was the first artist in the history of modern technology to record the complete Beethoven sonatas. When asked about the impact of his teacher, Schnabel responded, “I am unable to say, to estimate, or to appreciate what I learned from Leschetizky. He succeeded in releasing the vitality and sense of beauty a student had in his nature, and would not tolerate any deviation from what he felt to be truthfulness of expression. All this devotion, seriousness, care, and honesty are compatible with a virtuoso.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 30, Op. 109 (Artur Schnabel, piano)

Ignace Paderewski

In his day, the name Ignace Paderewski (1860-1941) became synonymous with the highest level of piano virtuosity. He crossed the Atlantic more than thirty times, and played more than 1,500 concerts in the US alone. A contemporary critic wrote, “Each recital was a spiritual happening! He excelled in the art of producing beautiful and varied tone colors never before dreamt of in a piano—from the lightest and most sparkling to the most violent extremes, which sounded almost orchestral.” Paderewski joined the Leschetizky studio at the ripe age of 24, initially studying with the master for two years. He subsequently undertook another course of study, but that second period of instruction was interrupted by concert engagements in the United States. Paderewski and Leschetizky remained close friends, and Paderewski generous underwrote scholarships for talented but financially disadvantaged Leschetizky students. He would also contribute a chapter to Malwine Bree’s handbook on the Leschetizky method. “Paderewski was arguably the most sought after pianist in the world of classical music, his playing characterized by a warm vibrant tone and an engaging use of rubato.” With a charming personality, attractive countenance, and a tireless constitution, he travelled the world and eventually became the prime minister and foreign minister of Poland, representing his native country at the Paris Peace Conference.

Frédéric Chopin: Polonaise No. 3, Op. 40, No. 1 “Military” (Ignace Paderewski, piano)

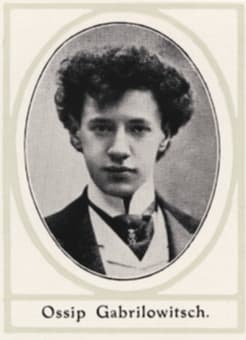

Ossip Gabrilowitsch, 1894

Ossip Gabrilowitsch (1878-1936) started his education at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. He studied piano and composition with such illustrious artists as Anton Rubinstein, Anatoly Lyadov, Alexander Glazunov, and Nikolai Medtner. Immediately after his graduation in 1894, Gabrilowitsch moved to Vienna and studied piano with Leschetizky for two years. Leschetizky considered Gabrilowitsch as one of the greatest representations of his teaching, and he also greatly valued him as a composer. Remembering his time with Leschetizky, Gabrilowitsch wrote, “What Leschetizky was concerned about was the meaning of a composition as a whole, its poetic message and musical construction, then the beauty of tone with which it could be expressed…”

Ossip Gabrilowitsch: Theme and Variation for Piano, Op. 4 (Tobias Bigger, piano)

Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler

Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler (1863-1927) was Leschetizky’s first American student. At the age of 11, she played for Annette Essipova, who had been a Leschetizky student and also his wife. She immediately recommended that Fannie travel to Vienna and study with Leschetizky at the Vienna Conservatory. Fannie arrived in 1879 and “Leschetizky complimented her precise and powerful playing, even calling her an electric wonder.” Zeisler returned to the United States and President Taft called her “America’s greatest pianist.” Her fame as a concert pianist also translated into Zeisler becoming one of the most coveted piano teachers. In following Leschetizky’s example, she emphasized the uniqueness of each student. She offered piano lessons exclusively in her home, with as many as 30 students attending at the same time. Each student received individual instruction during the class while the others observed and learned from the lessons.

Moritz Moszkowski: Liebeswalzer, “Frühling,” Op. 57, No. 5 (Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler, piano)

Mieczyslaw Horszowski, 1902

Mieczyslaw Horszowski (1892-1993) was only seven years of age when he began his studies with Leschetizky. His fellow students had great affection for his “quick ability to assimilate every concept or idea that Leschetizky put into his mind.” Ethel Newcomb wrote, “Horszowski ran home as soon as his mind grasped one fundamental of technique or tone, and incorporated it into every piece that he knew, turning it over in his philosophical little great brain until every possibility was grasped.” Horszowski remembered that Leschetizky “emphasized curved finger tips and a low wrist, as well as assigning certain etudes, Czerny’s etudes Op. 299 and Op. 740, as a means by which the mechanism can be kept loose and flexible.” Horszowski excelled in performances of Bach, Mozart, Chopin, Beethoven, and Brahms, and he was eagerly engaged as a chamber musician. He was the longest surviving Leschetizky student, playing his last recital in 1991.

Johannes Brahms: Violin Sonata No. 1, Op. 78 (Joseph Szigeti, violin; Mieczyslaw Horszowski, piano)

Mark Hambourg

Mark Hambourg’s (1879-1960) studied with Leschetizky for four years. When Annette Hullah first heard him perform, she wrote, “Now began the really exciting part of the evening, for it was little Mark Hambourg’s turn…Mark excelled himself and put everyone else in the shade. There seems to be nothing he cannot do, and his electricity is absolutely phenomenal… Professor turned round to us and murmured, he has a future—he can play.” Hambourg remembers, “Of course, it was from that great teacher, Leschetizky, that I learned most everything, not only pertaining to piano playing, but in regard to every aspect of how to live. As for a pianoforte lesson with him, it was a life experience, if one was capable of understanding what he wanted; and he had a wonderful way of explaining every detail with the utmost precision and care. He was not only marvelous at developing facility and brilliance of execution in his pupils, but also focused his teaching enormously on the quality of sound produced. Everything had to be beautiful and polished with him, and alive with the right kind of expression and feeling. He never allowed anything to pass his judgment that was dull, monotonous, or harsh in tone production…”

Mark Hambourg: Variations on the theme of the 24th Solo Violin Caprice by Paganini (Tobias Bigger, piano)

Alexander Brailowsky

Ukrainian by birth, Alexander Brailowsky (1896-1976) commenced his studies at the Kiev Conservatory before studying with Leschetizky. He was the first pianist to “perform Chopin’s entire repertoire in public concert,” and he probably best “represented Leschetizky’s philosophy of music and life.” He wrote, “genuine lasting success at the keyboard is not nearly so much a matter of fingers as it is of a highly trained intelligence, broad human experience, deep emotions, world sympathy, love for the beautiful, and the culture that comes with being highly educated…The virtuoso becomes the property of his art and of his public. He is a missionary of the musical gospel. He must consecrate himself to all that is fine and lofty and beautiful in life. These things Leschetizky transmuted into musical interpretations.”

Frédéric Chopin: Piano Sonata No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 58 (Alexander Brailowsky, piano)

Benno Moiseiwitsch

Benno Moiseiwitsch (1890-1963) was one of the best Leschetizky students, and one of the great pianists of the 20th century. He first took piano lessons at the age of 7 at the Imperial School of Music in Odessa, and only two years later won the Anton Rubinstein Prize. He joined his older brother John in London, but was told at the Royal Academy of Music that they could not teach him anything. As such, Benno and his brother travelled to Vienna to play for Leschetizky, who initially rejected him as a student. Apparently, Benno was told to “exercise more control and return in a few months.” When Benno returned, he was accepted and studied with Leschetizky for a number of years. Moiseiwitsch had infallible technique and stage persona, and “his musical phrasing possessed an inherent flexibility, supplemented by a seemingly infinite variety of tonal variations.” Rachmaninoff himself is known to have greatly admired Moiseiwitsch’s interpretations of his works.

Robert Schumann: Carnaval, Op. 9 (Benno Moiseiwitsch, piano)

Ignaz Friedman

Ignaz Friedman (1882-1948) initially learned his pianistic craft in Kraków, and by 1900 he took composition lessons from Hugo Riemann at the Leipzig Conservatory. At the age of 19, Friedman went to Vienna for lessons with Leschetizky. As with Benno Moiseiwitsch, Leschetizky was initially not enthusiastic. Leschetizky was clearly not enthused by supremely talented but over-confident youngsters. Eventually, however, he took the young Friedman under his wing and after three years of study he became one of Leschetizky’s teaching assistant. Scholars have suggested that Friedmann is “perhaps the greatest example of Leschetizky’s teaching on tonal production; he possessed a warm, golden tone that was the envy of many pianists of his time.” Friedman explained, “In all of his teaching, Leschetizky paid more attention to tone than to technic, quite the opposite to the opinion generally held. He would often shout at me in the course of a lesson ‘tone, tone, tone! Always more TONE!’” As with countless Leschetizky students, Friedman evolved into a highly respected teacher, passing on the legacy of his teacher to future generations.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies, S244/R106: No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor (Ignaz Friedman, piano)

My great Uncle, Waddington Cooke

He studied at the School he became famous in England as a pianist and composer.

He played for Queen Victoria at some time.

What about Franz Schmidt and Ernst von Dohnányi?

My piano teacher Robert Gregory was taught in Vienna by Leschetizky. He was a wonderful teacher, taught by Carl Czerny, who was taught by Beethoven and passed down the Leschetizky Method. I have a copy of the book.

My grandfather, Emil Friedberger 1879-1963 studied with Leschetitzky in Vienna at the conservatory and I also have his pages of notes of the method with pages of exercises . Woukd love to speak with you about your copy of the method . [email protected]. 954-648-9255

My grandfather , Emil Friedberger studied at the Vienna conservatory with Julius Epstein and then with Leschetitzky . He knew Mahler and Brahms and in fact recalled having played a 8 hand arrangement , for Mahler , of one of his symphonies. With him at the piano were prof epstein and Heinrich schenker ! He left behind many well notated scores of the great works of Brahms, Beethoven , Chopin and Schumann that he had studied and performed many times during his long career as performer and teacher

I know that my teacher Linda Friedland (nee Rosenblum) studied with Emil Friedberger…would love to know more and also see the line of succession from Beethoven