Amarillis crowning Mirtillo by Jacques Loo

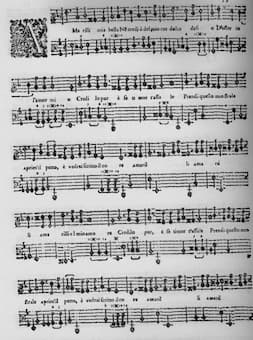

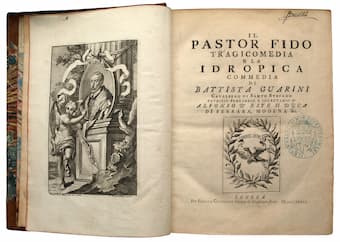

Giovanni Guarini started work on his pastoral tragicomedy “Il pastor fido” (The Faithful Shepherd) around 1580. It took him a good four years before he was able to finish the five-act, 39-scene pastoral drama. Guarini circulated the play among literary circles for criticism and quickly came under fire for not adhering to the Aristotelian rules of dramatic structure. Guarini wrote a polemic defense of tragicomedy, believing that “the proper aim of the modern playwright was not the purgation of the tragic emotions of the ancients—pity and terror—but rather the banishment of melancholy. This mixed genre combined and moderated traits from both tragedy and comedy and the final outcome was comic.” Guarini first published “Il pastor fido” in Venice in 1590, and by 1602 it had gone through an astonishing 20 Italian editions. During the 1590’s, at the height of pastoral vogue, more than 550 madrigals by 125 composers had found inspiration in that particular play.

Luca Marenzio: “Cruda Amarilli” (La Pedrina; Francesco Saverio Pedrini, cond.)

Il Pastor Fido Act IV

There is plenty of tension between moral authority and sensual desire in the play, and drawing on both tragic and comic elements, the plot is considerably complex. Montano, the chief priest of Arcadia plans to marry his son Silvio to Amarilli in order to lift an ancient curse. The gods of Arcadia demand the sacrifice of a virgin every year, and the curse can only be lifted when a young man and young woman of godly descent, are wed. It’s not all that easy, however, because Silvio is much more interested in hunting than in love, and Amarilli is secretly loved by the foreign shepherd Mirtillo. One strain of this double plot follows Silvio, who is pursued by the nymph Dorinda. She tries everything in her power to attract Silvio, but he is simply not interested. One day, she follows him on a hunt disguised as a shepherd wearing wolfs skin clothes. When she lays down to rest, Silvio mistakes her for a wolf and shoots her with an arrow. Having seriously wounded Dorinda, Silvio finally becomes away of pity and of love.

Benedetto Pallavicino: “Cruda Amerilli” (Daltrocanto; Dario Tabbia, cond.)

Giulio Caccini’s Amarilli mia bella

The love between Amarilli and Mirtillo has to remain secret, as she is well aware of her responsibility of having to marry Silvio. She publically spurns Mirtillo’s advances, but reveals in her famous soliloquy that she is secretly in love with him. The wicked nymph Corisca overhears this heart-felt confession of love, and she is rather indignant. In fact, Corisca is also in love with Mirtillo and plans to seduce him. To complicate matters even further, Corisca is loved by the shepherd Coridon, a lusty satyr, and the old man Satiro. When she rejects her suitors, Satiro swears revenge. Knowing Amarilli’s secret, Corisca now sees a chance to eliminate her rival. She gains Amarilli’s trust, and tells her that Silvio is in love with the nymph Lisetta, and that they will secretly meet in a cave.

Giulio Caccini: “Amarilli mia bella” (Kei Fukui, tenor; Anthonello)

Salamone Rossi

Amarilli rushes to the cave hoping to catch the couple together, as she will thus be able to escape marriage to Silvio. In the meantime, Corisca tells Mirtillo that Amarilli will secretly be meeting a shepherd in the same cave. Mirtillo is outraged and is ready to confront Amarilli and her lover. He plans to kill them both, and then to kill himself. When Satiro sees Mirtillo entering the cave, he wrongly concludes that Mirtillo is going to meet Corisca. He blocks the cave with a giant rock, and runs off to fetch the priests. Things, however, don’t unfold as planned since it is actually Mirtillo trapped in the cave with Amarilli. The priest Montano, Silvio’s father, discovers them and he condemns Amarilli to die as a sacrifice to the gods.

Salamone Rossi: “O Mirtillo, Mirtillo” (Ut Musica Poesis Ensemble; Stefano Bozolo, cond.)

Arcadia by Markó Károly

Mirtillo demands to be sacrificed instead, as he plans to take Amarilli’s place. However, it is discovered at the very last second that Mirtillo is really Montano’s long-lost son, so now Amarilli and Mirtillo can be married and still fulfill the demands of the oracle. It’s time for a double wedding, as Silvio also marries the healed Dorinda. In the end, Corisca is converted from the evil ways by the sight of the happiness of the lovers. The characters in the play are from various ranks of society, ranging from the noble lovers to the spiteful satyr. Guarini includes several comic moments, highlighting the escapism of the genre. He skillfully takes the audience to a point where they fear for a tragic ending, but at the last instance provides a happy end. The pastoral setting greatly enhances a sense of escape, as the action takes place away from a courtly setting and is placed in an idealized land of Arcadia. This sense of exile permeates much of the pastoral literature in the Italian Renaissance, and in this “Garden of Eden,” happiness can only be glimpsed from the outside.

Claudio Monteverdi: “O Mirtillo, Mirtillo anima mia, SV 95” (Consort of Musicke; Anthony Rooley, cond.)

Guarini’s Il Pastor Fido

Guarini’s texts are “dramatically and rhetorically sophisticated, making frequent use of word pairs and double meanings; they also engage frankly with themes of love, eroticism, and the complex emotions that accompany them. In the play, “Cruda Amarilli” are the first words heard from Mirtillo, a shepherd foreign to Arcadia. Mirtillo believes his love is unrequited and his opening monologue expresses the conflict over loving Amarilli and the pain of her rejection.

Cruda Amarilli, che col nome ancora,

D’amar, ahi lasso! amaramente insegni;

Amarilli, del candido ligustro

Più candida e più bella,

Ma de l’aspido sordo

E più sorda e più fera e più fugace;

Poi ché col dir t’offendo,

I’ mi morrò tacendo.

Cruel Amaryllis, who with your name

to love, alas, bitterly you teach;

Amaryllis, more than the white privet

pure, and more beautiful,

but than the deaf asp,

both deafer and fiercer and more elusive;

since in speaking I offend you,

I shall die in silence.

Claudio Monteverdi: “Cruda Amarilli, che col nome ancora” (Rossana Bertini, soprano; Claudio Cavina, alto; Sandro Naglia, tenor; Giuseppe Maletto, tenor; Daniele Carnovich, bass; Concerto Italiano; Rinaldo Alessandrini, cond.)

Claudio Monteverdi

It immediately becomes clear that Mirtillo believes Amarilli’s love to be beautiful but also fierce and fleeting. Scholars have argued that the first two line of the poem point to a double meaning in the name Amarillis, “since in Italian the word ‘amar’ serves as the root for both love and bitterness.” The poem appears to present a number of challenges in terms of musical settings. “There are no words that allow for obvious word painting, and a composer would need to deal with expressing the textual meaning for words like ‘deaf,’ and ‘silence’ in a medium of sound production.” The famed setting of Claudio Monteverdi pays special attention to the correlation between dissonance treatment and specific words. In short, the meaning of words set to music should be more important than beauty of traditional counterpoint. This new concept was termed “seconda partica,” and asserted that the “text should be the mistress of the music, not the slave of it.”

Sigismondo D’India: “Crud’Amarilli, che col nom’ancora” (Ensemble Arte Musica; Francesco Cera, cond.)

Sigismondo D’India

Since duality and emotional conflict were major themes in Italian madrigal texts, Monteverdi’s pattern of modal cadences makes clear references to the text. He also places great emphasis on declamation, incorporates surprising harmonic effects and makes use of frequent unprepared dissonances. Sigismondo D’India, on the other hand, uses a different expressive strategy. His setting, from the first book of madrigals in 1607 “can be read as taking place outside the action of Guarini’s play. The setting resides on a different rhetorical plane and perceives Amarilli not as a duality but as ambiguous.” As I mentioned earlier, madrigal settings number in the hundreds, but only two scenes from the play were set to music in their entirety. Yet, Guarini’s tragicomedy influenced the style and content of opera and cantata until the time of Metastasio and Handel.

George Frideric Handel: Il Pastor fido (Paul Esswood, counter-tenor; Katalin Farkas, soprano; Marta Lukin, mezzo-soprano; Gabor Kallay, tenor; Maria Flohr, mezzo-soprano; Jozsef Gregor, bass; Savaria Vocal Ensemble; Savaria Capella; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

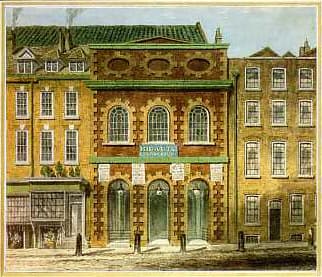

King’s Theatre, Haymarket

Speaking of Handel, once George Frideric had honed his compositional craft in Italy, he settled in London. In 1711 he first brought Italian opera to the London stage with his opera Rinaldo. It proofed a tremendous success, and he followed it up with the simple pastoral tale “Il Pastor Fido” to a libretto by Giacomo Rossi based on Guarini’s original. Handel had hoped that Guarini’s famous play would find a receptive audience. In the event, the opera did not do well, with the historian and critic Charles Burney writing, “the whole is inferior in solidity and invention to almost all his other dramatic productions, yet there are in it many proofs of genius and abilities which must strike every real judge of the art, who is acquainted with the state of dramatic Music at the time it was composed.” Handel did revise the work twenty years later and the revival was much more successful.

Nicolas Chédeville (Antonio Vivaldi): Flute Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Op. 13 “Il pastor fido” (Roberto Fabbriciani, flute; Carlo Denti, viola da gamba; Robert Kohnen, harpsichord)

Nicolas Chédeville

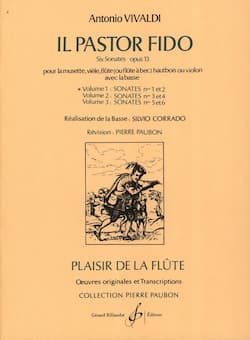

“The Faithful Shepherd” also made an appearance in a collection of six sonatas originally attributed to Antonio Vivaldi. However, the work was actually composed by the French musette player and maker, Nicolas Chédeville. To stimulate sales for his musettes—a double-reed baroque instrument belonging to the bagpipe family—Chédeville entered into a secret publishing agreement with the firm of Jean-Noël Marchand. This agreement stipulated that Marchand would publish the Chédeville compositions under the name of Antonio Vivaldi, thereby enhancing the marketability of the collection. Chédeville covered the cost of publication—it eventually reached its intended wealthy amateur-musician market in 1737—and in return he received all profits from sales.

Vivaldi’s Il Pastor Fido

Guarini was born into a prominent family of humanist scholar, but his “ugly and ambitious character made life somewhat difficult.” He constantly squabbled with patrons and employers, and the only one of his eight children with whom he wasn’t in constant and deep conflict died tragically. Anna was a celebrated singer, and she was brutally murdered by a jealous husband under accusations of adultery. Guarini spent his final restless and gloomy years immersed in nasty legal, employment and family battles, but his dramatic and lyric genius decidedly captured the European imagination.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Claudio Monteverdi: “Ah, dolente partita” (Delitiæ Musicæ; Marco Longhini, cond.)