There never was, and never will be, a defining boundary between music and the other arts. The arts are constantly engaged in a process of circular cross-fertilization that continuously shape and refine artistic practices, visual expressions and sonic experiences. We generally think of musical settings inspired by poetry, paintings and sculpture. However, music has just as frequently provided the initial impulse. As the painter Wassily Kandinsky famously put it, “Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, and the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.”

Max Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie

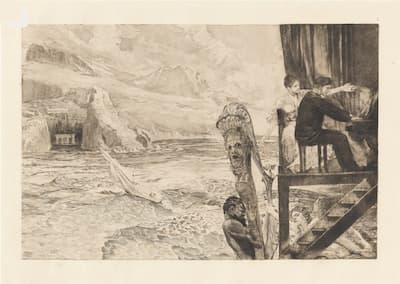

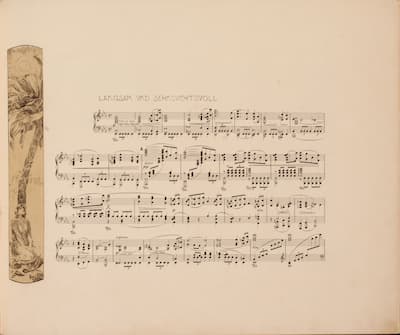

Let us explore some of these vibrations in the soul, starting with the Max Klinger’s “Brahms Fantasy Opus XII”. This cycle of 41 engravings, etching and lithographs is based on the music of Johannes Brahms. The graphic images appear in dialogue with musical scores for five songs and the “Schicksalslied” (Song of Destiny) Op. 54 for chorus and orchestra by Johannes Brahms.

Max Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie: Song of Destiny

The graphic images are not illustrations; they are, as the title indicates, independent fantasies on the music and texts. This unique work of “visual music” extends the impression made by two-dimensional images into acoustical space. Brahms himself commented to Klinger, “I see the music, together with the words, and your splendid engravings carry me away. Beholding them, it is as if the music resounds farther into the infinite and everything expresses what I wanted to say more clearly than would be possible in music, and yet still in a manner full of mystery and foreboding. I must conclude that all art is the same and speaks the same language.”

Johannes Brahms: Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny), Op. 54

Walt Whitman

The American poet Walt Whitman strongly rebelled against such aristocratic forms of entertainment as opera. “He believed America should develop it’s own kind of music, and should not by any means subscribe to such un-American and meaningless drivel.” He strongly believed that Italian opera was too artificial and complicated, and he penned scathing editorial reviews to that effect. But all this changed when he suddenly found himself under the spell of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti.

Walt Whitman: Song of Myself

Opera, in the end, was so important to Whitman that he claimed, “it was essential to conceiving and writing his enormous poetry collection Leaves of Grass,” which contains hundreds of musical terms, as well as the names of composers and performers. A scholar suggested, “as Whitman experienced opera, he had a distinctly erotic response to it. The power of the voice penetrated the ears of the listener and in that way became a transporting experience.” The poet started to view opera as a way to bridge social gaps and bring people together on a subconsciously experienced level of beauty. As he wrote in his expansive poem “Song of Myself.”

I hear the train’d soprano (what work with hers is this?)

The orchestra whirls me wider than Uranus flies,

It wrenches such ardors from me I did not know I possess’d them.

Gaetano Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor, “Eccola”

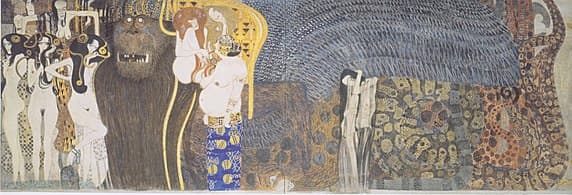

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) started his artistic career as a successful painter of architectural decorations, but his paintings with its primary focus on the female body, were criticized as pornographic. Together with a group of like-minded artists, Klimt founded the Austrian Association of Visual Artists Secession. The goals of the group were to “provide exhibitions for unconventional young artists, to bring the works of the best foreign artists to Vienna, and to publish its own magazine to showcase the work of members.” Between 1898 and 1905, the association organized 23 groundbreaking exhibitions at the Secession building, with the 14th Secession exhibition dedicated to the 75th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven’s death.

The stated aim of the exhibition was to reunite individual artistic genres—architecture, painting, sculpture and music—through a common theme. As such, Klimt painted a 34-meter long wall cycle Beethoven Frieze as an example of the interplay of interior decoration and mural art. The inspiration, however, came from music. Specifically, it came from Beethoven’s 9th symphony in the arrangement by Richard Wagner.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 “Molto vivace” (arr. Richard Wagner) (Yoshie Hida, soprano; Yuko Anazawa, alto; Makoto Sakurada, tenor; Chiyuki Urano, baritone; Noriko Ogawa, piano; Bach Collegium Japan Chorus; Masaaki Suzuki, cond.)

Virginia Woolf on Time Magazine Cover, 1929

The English modernist author Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) is widely considered one of the most important 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the “use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.” The connections between her literary innovations and the works of contemporary composer had been noted early on, but scholars only “began to explore her extraordinary experimental uses of narrative perspective, repetition and variation derived from her close study of particular musical works and specific musical forms” later. As a young woman, Woolf attended operas and concerts several times a week, and she received a basic music education. She was a most attentive listener, and she loved the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Wagner. However, she also delighted in the music of Arnold Schoenberg and other avant-garde composers.

Virginia Woolf by Roger Fry, 1917

Her novels are “significantly shaped by her enduring, passionate love of music, and social attitudes towards music also inform her critiques of women’s unequal access to music education.” Woolf drew direct inspiration from the Ballets Russes repertory, especially “Les Noces.” The rhythm and organization of her material, and her ideas about kinetic momentum were decisively shaped by her ballet experiences. “Music provided Woolf with a vocabulary to imagine and describe her creative practice and formal innovations.” As she famously wrote, “it’s odd, for I’m not regularly musical but I always think of my books as music before I write them.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: Les Noces (Excerpt)