John Henry: Symphony in Red

The internationally renowned sculptor John Henry has produced a substantial number of monumental and large-scaled works across the United States, Europe, and Asia. His sculptures resemble huge welded steel drawings, “arranging linear and rectilinear elements that appear to defy gravity and float.” It has been suggested that his sculptures “capture a moment of arrested motion where flying and tumbling elements are frozen.” His sculptures are placed in museums, and public institutions. However, they have also become part of city landscapes, as with his “Symphony in Red,” placed at the intersection of an important transport hub in Hanover, Germany.

John Henry: Symphony in Red

Five lanes of traffic come together at the “Königsworther Platz,” creating a complex and dynamic environment. The sculpture reflects the complexity of the location, and despite its monumentality, it projects simple elegance and an unexpected sense of immediacy and lightness. We don’t know what specific symphony John Henry had in mind, but Mahler’s monumental, all-encompassing, and universal 3rd symphony seems a perfect fit.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3, “IV-VI” (Waltraud Meier, mezzo-soprano; Eton College Boys’ Choir; London Philharmonic Choir; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Klaus Tennstedt, cond.)

Marc Chagall, c.1920 by Pierre Choumoff

Marc Chagall (1887-1985) was an exceptional Jewish artist associated with several major artistic styles. He created works in a wide range of artistic formats, including painting, drawings, book illustrations, stained glass, stage sets, ceramics, tapestries and fine art prints. His works are considered “not only the dream of one people but of all humanity.” Pablo Picasso wrote in 1954, “Chagall is the only painter who understands what colour really is.” Chagall has always maintained that “Colour is everything, colour is vibration like music, and everything is vibration.”

Marc Chagall: Daphnis and Chloe in the Cave of the Nymphs

From the very beginning, music was at the heart of Chagall’s art, and the violin was an important symbol in the cultural and religious setting of his childhood. Above all, he loved the works of Bach and Mozart. His collaborations through classical music are legendary, as he painted the ceiling of the Paris Opera House and the famous Met Lincoln Center panels. He also created the scenery and costumes for the NYC Firebird, and for Ravel’s “Daphnis and Chloe.”

Marc Chagall: Philetas’s Orchard, from Daphnis and Chloe

That romantic Greek fable and Ravel’s music served as the inspiration for 42 coloured lithographs. His illustrations are vibrant and luminous, “infused with dazzling Mediterranean colour and light, conveying both the innocence and passion of first love. The characters float in pastoral scenes filled with flowers, animals and mythological figures, on a background of meadows, mountains, and seas, in perfect harmony with nature.”

Ravel/Chagall: Daphnis et Chloe (Excerpts)

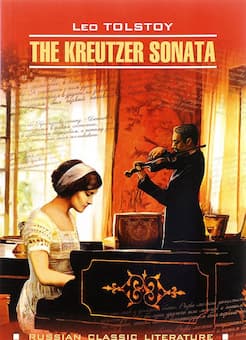

Leo Tolstoy: The Kreutzer Sonata

The outstanding Russian novelist and writer Leo Tolstoy published his novella titled “The Kreutzer Sonata” in 1889. As is well known, the title makes reference to Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9, Op. 47. It is a composition of intense emotions, and it served Tolstoy as the rousing backdrop for his narrative. The main character falls in love and marries the woman of his desire. As they get settled into marital routine, and after having a number of children together, the wife falls in love with a violinist. They fell in love performing the “Kreutzer Sonata” together, and when the husband returns early from a trip, he finds the violinist and his wife together. He kills his wife with a knife, but the violinist escapes. In the end, the husband is acquitted of murder and endlessly rides the trains seeking forgiveness. Tolstoy’s novella was quickly condemned as the work of “a sexual moral pervert,” and censored in Russia. Tolstoy was severely criticized for “disliking being a man, and pitying humanity because it is human.” Less charitable voices decried that “animal excesses and swinish connections are not the fundamental basis for the relations between the sexes.” Leoš Janačék, in turn published his first string quartet under the subtitle “The Kreutzer Sonata.” According to the composer “the music mirrors the psychological drama of love, jealousy and murder detailed in the literary work.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9, Op. 47 “Kreutzer”

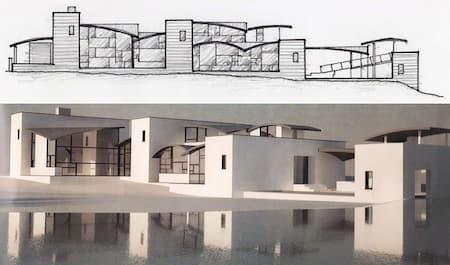

Steven Holl: Stretto House

In the city of Dallas, Texas, clients with an extraordinary art collection approached American architect Steven Holl for a house design. The architect visited the proposed site, and he found a landscape with a flowing river feeding three independent ponds. Holl started to search for a musical composition that was structured like the water flowing on the site. In the end he was told about the musical process called “stretto,” where musical phrases overlap one another.

For there, it wasn’t long before he found the music of Béla Bartók, and specifically his “Music for strings, percussions and celesta” written in 1936. The composition is divided into four parts and Bartók’s work constantly overlaps heavy percussion with light string instruments. For Holl, “powerful flows of rhythmical divisions and irregular tensions made time seem to stand still or to rush forward with irresistible momentum.”

For there, it wasn’t long before he found the music of Béla Bartók, and specifically his “Music for strings, percussions and celesta” written in 1936. The composition is divided into four parts and Bartók’s work constantly overlaps heavy percussion with light string instruments. For Holl, “powerful flows of rhythmical divisions and irregular tensions made time seem to stand still or to rush forward with irresistible momentum.”

It took Holl six month to design the “Stretto House” eventually built with traditional materials. The house encompasses four sections, each divided into two units; the first is rectangular heavy masonry, and the second is constructed of light curvilinear metal. The interplay between heavy straight lines and light curves is reversed in the guesthouse analogous to the inversions of subjects in Bartók’s music. Critic have suggested, the “Stretto House” appeals to the senses and plays upon artistic perception, analogous to Bartók’s composition.”

It took Holl six month to design the “Stretto House” eventually built with traditional materials. The house encompasses four sections, each divided into two units; the first is rectangular heavy masonry, and the second is constructed of light curvilinear metal. The interplay between heavy straight lines and light curves is reversed in the guesthouse analogous to the inversions of subjects in Bartók’s music. Critic have suggested, the “Stretto House” appeals to the senses and plays upon artistic perception, analogous to Bartók’s composition.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Béla Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (Cleveland Orchestra; Christoph von Dohnányi, cond.)