Cécile Chaminade

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) was the first woman composer ever to be awarded with the legion d‘honneur in 1913. The composer Ambroise Thomas said, “This is not a woman who composes, but a composer who is a woman.” Chaminade was well aware of the social and personal difficulties facing a woman composer, “and she suggested that perseverance and special circumstances were needed to overcome them.” As such, she composed approximately 400 compositions—mostly piano works and melodies—expressly written for publication and sale. “Though the narrower focus may have been due to financial, aesthetic or discriminatory considerations, this music became very popular, especially in England and the USA.” She helped to promote sales through extensive concert tours and found especially fertile grounds in the United States. “Chaminade Clubs” had started to form and her pieces became favorites in piano anthologies of the time. While financially successful, critical evaluation was mixed. “Pieces deemed sweet and charming, especially the lyrical character pieces and songs, were criticized for being too feminine, while works that emphasize thematic development were considered too virile or masculine and hence unsuited to the womanly nature of the composer.”

Cécile Chaminade as sketched by Marguerite Martyn

in St. Louis, November 1908

Her music is described as tuneful and accessible, “with memorable melodies, clear textures and mildly chromatic harmonies.” A good many of her compositions are said to be “well-suited expressively and poetically to the ambience of the salon or the recital hall, the likely sites for such works.” Her 2nd Piano Trio dates from 1887, and although it is a relatively early work, the composition embraces traditional forms while “feeling organically spun end-to-end with some striking and distinctive contrapuntal flair.”

Chaminade was one of the rare female composers who were publicly celebrated in her lifetime, but her reputation sharply declined as the 20th century progressed. Scholars attribute this “partly to the rise of modernism and a general disparagement of late Romantic French music, but it is also due to the socio-aesthetic conditions affecting women and their music.” Catchy melodies, captivating harmonies, and consistently brilliant displays of virtuosity laid the foundation for Chaminade’s unmatched popularity during her lifetime, and fortunately her music is being rediscovered in the 21st century.

Cécile Chaminade: Piano Trio No. 2 in A minor, Op. 34 (Annette Mannheimer, violin; Sara Wijk, cello; Ann-Sofi Klingberg, piano)

Rebecca Clarke

Rebecca Clarke (1886–1979) was born and raised in England, but relocate permanently to the United States after the outbreak of World War II. She was a prominent concert violist both at home and abroad, and highly active in chamber and symphonic ensembles. In fact, she became one of the first female musicians in a fully professional ensemble, when Henry Wood admitted her to the Queen’s Hall orchestra. She had also been the first woman to study composition with Charles Stanford at the Royal College of Music. Clarke achieved fame as a composer with her Viola Sonata and the Piano Trio, and she has been described as “the most distinguished British female composer of the inter-war generation.” However, lack of encouragement and even hostile discouragement made it difficult to have her compositions published. The works published during her lifetime were largely forgotten, and good portion of her music has yet to be published. More recently, the Rebecca Clarke Society was established in 2000 to promote the study and performance of her music.

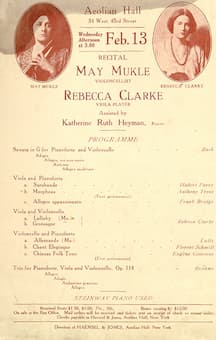

Rebecca Clarke and May Mulke performance program at the Aeolian Hall, 13 Feb, 1918

Morpheus, a work for viola and piano named after the Greek god of sleep and dreams, was premiered in New York in 1918. Clarke was touring with her colleague May Mulke, and the recital at Aeolian Hall actually included two works by Clarke. The first work listed Clarke as composer, but Morpheus was programmed under the male pseudonym “Anthony Trent.” Seemingly, Clarke was self-conscious about her name appearing multiple times on one concert program. She explained, “I thought how silly to have my name on the programme yet again.” Tellingly, critics “paid much more attention to the piece attributed to Mr. Trent.” That’s a shame because Morpheus uniquely “develops a single melody through coloristic devices such as pentatonic glissandos on the piano and artificial harmonics on the violin.”

Rebecca Clarke: Morpheus (Malin Broman, viola; Simon Crawford-Phillips, piano)

Grażyna Bacewicz

The Polish violinist, pianist, and composer Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969) has been described as one of the most “significant voices in European music of the twentieth century.” A graduate of the Warsaw Conservatory, she received a scholarship awarded in honor of Ignacy Paderewski to study in Paris. As such, she took lessons with the famed Nadia Boulanger and the violinist André Touret in1932 and 1933, and returned for lessons with Carl Flesch in 1934. Bacewicz performed as a violin soloist in many European countries, and she was also known for her prowess as a pianist. However, Bacewicz made her mark on 20th-century music as a composer rather than as a performer and teacher. Her compositional development initially focused on clarity, wit and brevity practices by neo-classical streams, while her works from the time of World War II “show a greater muscularity and daring disregard for traditional classical structures.” Her music became increasingly personal, and she used folk materials both directly and indirectly.

Grażyna Bacewicz

Bacewicz was committed to exploring new techniques but never lost sight of her own personal voice. As Lutosławski observed, “To judge her works only in light of the compositional styles and rapidly changing artistic currents of her lifetime does not appear to me to be proper. Like so many other composers of larger compositional forms, she was to a great degree independent from the atmosphere surrounding her. Rather, it was her music that helped to create that atmosphere and could be held up as an example to the younger generation of composers.” She composed her String Quartet No. 3 in Paris while on a concert tour. Lutosławski commented that it “is marked by an exceptional polyphonic skill in addition to its masterly idiomatic writing for string quartet.” Bacewicz’s musical achievements have been widely recognized, and she set a shining example for many women composer who followed in her footsteps.

Grażyna Bacewicz: String Quartet No. 3 (Lutosławski Quartet)

Pauline Viardot-García

Without doubt, the García family of musicians had a tremendous impact on the history of opera and singing in their various countries of residence. Manuel del Pópulo García was a highly esteemed tenor, composer and singing teacher. He was married a number of times, but his famous daughters Maria Malibran and Pauline Viardot were born to his longtime companion Maria Joaquina Sitches, a member of his touring company. At one time or another, the family resided in Naples, London, Paris and New York.

Paul Viardot

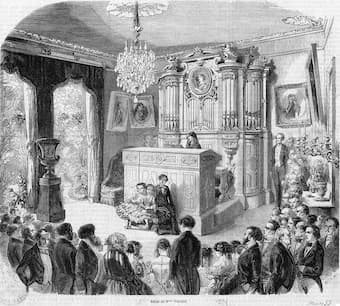

Pauline studied piano and voice with her father, and in the course of time became one of the most important singers and teachers of the 19th century. In addition, she took composition lessons with the famed Czech Antonin Reicha, and she was held in the highest esteem as a pianist. She held artistic salons in Paris and Baden-Baden, and these vibrant cultural and artistic meeting places launched the careers of Camille Saint-Säens, Jules Massenet, Gabriel Fauré, and Charles Gounod. Highly educated, she spoke five languages and counted Clara Schumann, George Sand, Charles Gounod, and Turgenev among her closest circle of friends.

Salon of Pauline Viardot

Viardot did not regard herself as a composer, as her compositions emerged from the pleasure she took in music and drama. Her compositional activity is “strongly marked as her other artistic activities by the principle of aesthetic and cultural transfer: she strove to achieve neither a unified personal style nor a timeless masterpiece. Rather, she advocated a conception of music in which the key element was communication and mediation: communication between amateurs and professionals, between different stylistic orientations and levels, between different musical cultures.” She wrote German songs and ballads, French chansons, romances and mélodies. She worked closely with publishing houses in France, Germany and Russia, and her compositions achieved considerable popularity. Her son Paul was born in 1857 and became a celebrated violinist, conductor and composer. Viardot’s Six Morceaux pour Violon et Piano are dedicated to her son, “and give testimony to the unbelievable technical ease of the composer and her imaginative treatment of style, melody and harmony.”

Pauline Garcia-Viardot: 6 Morceaux (Thomas Albertus Irnberger, violin; Barbara Moser, piano)

Jennifer Higdon © J.D. Scott

Jennifer Higdon is a major figure in contemporary Classical music, and she is one of America’s most acclaimed and most frequently performed living composers. She received the 2010 Pulitzer Prize in Music for her Violin Concerto, and in the same year added a Grammy for her Percussion Concerto. In 2018 she won the Grammy for her Viola Concerto, and she followed that up with a 2020 Grammy for her Harp Concerto. Her music has been hailed as having “the distinction of being at once complex, sophisticated but readily accessible emotionally,” and “traditionally rooted, yet imbued with integrity and freshness.” Higdon composes in a wide range of genres, from orchestral to chamber and wind ensemble, as well as vocal, choral and opera. She receives countless commissions, and is a featured composer at various festivals. Composer-in-Residence with several orchestras, her music receives over 200 performances a year and has been issued on over 60 CDs.

Higdon’s progressive style emerges forcefully in her five-part composition String Poetic. Although the composer did not provide her listeners with a tangible program, she implies that “an echo of today’s world can be heard in the composition.” It has been described as a suite of modern songs without words, and critics discovered a work “marked by rhetorical clarity and dexterous interplay between the two instruments… But where Higdon’s spirits run high, the effects are crisp and venturesome.” Simultaneously committed to musical coherence and thematic development, Higdon creates colorful and expressive music. “In its incorporation of scales that are alien to western classical music and in its use of consecutive fifths, the suite demonstrates many individual and original compositional ideas.” Please join us next time for more chamber music composed by women, including works by Louise Farrenc, Amy Beach, Nadia Boulanger, Phyllis Tate and Liu Zhuang.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Jennifer Higdon: String Poetic (Louise Chisson, violin; Tamara Atschba, piano)