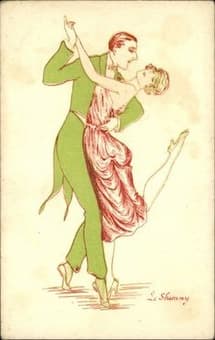

Couple dancing the Shimmy

Ah, Vienna! The city of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and the waltzing Lanner and Strauss families. Even today, Vienna likes to promote itself as the eternally waltzing city. While that may be the case to some extent, in the period between the two great wars of the 20th century, the city was dancing to an entirely different beat.

Julius Bittner

When George Gershwin traveled to Vienna in 1928, the house orchestra at the famous Café Sacher spontaneously played the opening of the Rhapsody in Blue as he entered. Gershwin laughed all the way to the bank, but his musical smorgasbord of combining elements from classical music with jazz influences fuelled a deep infatuation with American popular musical styles on the European musical landscape.

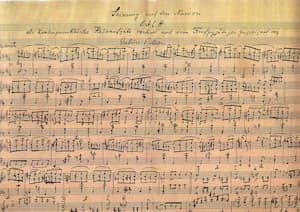

Julius Bittner: Shimmy on the name B.A.C.H

In turn, young composers born around the turn of the century were looking to reinvigorate classical music, and they found inspiration in a series of new dances originating from South and North America. Written for the 50th birthday of David Josef Bach, the music critic for the Viennese Arbeiterzeitung and an ardent jazz enthusiast, Julius Bittner’s Shimmy on the name B.A.C.H quotes the famous motif a total of nine times.

Julius Bittner: Shimmy auf den Namen Bach (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Ernst Krenek

In a public lecture given at the University of Vienna in 1925, Ernst Krenek (1900-1991) wondered what the listening public really wanted to hear. “The answer,” he said, “will perhaps be somewhat frightening; none other than dance music.” Krenek possibly thought it strange that the Viennese public would so enthusiastically take to jazz music. However, entertainment music had always been valued by the Viennese masses, whether it came in the shape of little bands at the cafes and beer gardens, military bands playing under little gazebos, or dance orchestras appearing in small community halls.

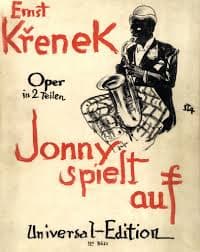

Ernst Krenek: Jonny spielt auf

The first American jazz band was heard in Vienna in 1922, and soon everybody was dancing shimmies, foxtrots, tangos and Charlestons. It is hardly surprising that these new and modern dances would make their way into different musical genres, including comedies, operettas and opera. And Krenek became an overnight sensation with his opera Jonny Strikes Up, which had its debut on 10 February 1927 in Leipzig. Krenek later admitted “when writing the opera, he had only very vague conceptions about real jazz,” but it is nevertheless a contemporary reflection on a new musical freedom, its settings and its symbols.

Ernst Krenek: “Potpourri” aus Jonny spielt auf (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Wilhelm Grosz

These series of new dances became a way to enjoy life, find physical contact and musical entertainment. And they quickly found a market as well, with the music publisher Universal Edition of Vienna launching a distinctive “Moderne Jazzmusik” series. In his African Songs, Wilhelm Grosz (1894–1939) had provided German-speaking audiences with translations of poems by Langston Hughes and Jean Toomer. His “Tanzsketch” Baby in the Bar was written in 1925/26 and premiered in Hanover in 1928. A surrealist pantomime of Freudian depth psychology, the story sees a proletarian woman abandon her newborn infant in an upper-class cocktail lounge. “In a demonstration of infant sexuality, the Baby then proceeds to seduce the customers to the strains of blues, tango, and foxtrot.” At the work’s climax, the hapless headwaiter succumbs to a “shimmy.”

Wilhelm Grosz: Baby in the Bar, Op. 23 (excerpts) (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Bohuslav Martinů

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) always paid close attention to avant-garde cosmopolitan musical developments. He composed in a variety of colorful styles and fluid forms, and Jazz harmonies happily mingle within an intricate network of counterpoint that one sculptor described his compositions “carved out of marble.” Martinů was never comfortable in the highly conservative musical environment of Prague. As such, he packed his bags in 1923 and sought more satisfying artistic pastures in Paris and beyond. A good many of his compositions assimilated these modern dance styles, and we find them not only in single piano pieces but also in his chamber and orchestral music. In the featured selection we find two works inspired by ragtime. The “Foxtrot” and the “One-step” quote from Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer,” respectively. Replacing the Charleston as the latest craze in popular dances, the “Black Bottom” dates from 1927.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Bohuslav Martinů: Foxtrot, H. 126bis (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Bohuslav Martinů: One-step, H. 127bis (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Bohuslav Martinů: Black Bottom, H. 165 (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)