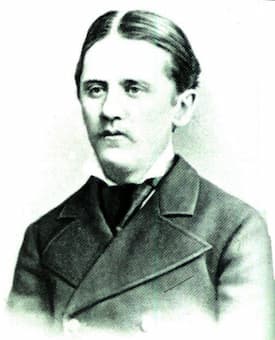

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky arrived in St Petersburg on 22 October 1893 to oversee the first performance of his Sixth Symphony. Tchaikovsky was elatedly optimistic and wrote, “I think it will be successful; it is rare for me to write anything with such love and enthrallment. I can honestly say that never in my life have I been so pleased with myself, so proud, or felt so fortunate to have created something as good as this.” Much of his time was devoted to orchestral rehearsals, and the first public performance under the auspices of the Russian Musical Society took place with Tchaikovsky conducting on 28 October. After the performance, Tchaikovsky reported, “Something strange is happening with this symphony! It’s not that it displeased, but it has caused some bewilderment. So far as I myself am concerned, I’m more proud of it than any of my other works.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 “Pathétique”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Just a couple of days later, after returning late from his favorite restaurant, Tchaikovsky experienced stomach discomfort. His condition worsened overnight, and the composer suffered from constant diarrhea and vomiting, extreme weakness, chest and abdominal pain. Greatly concerned, his brother Modest, summoned the family doctor who immediately diagnosed Asiatic cholera. The doctor believed that Tchaikovsky’s life was in real danger, “as the patient began to experience spasms, his head and extremities turned dark blue, and his temperature fell.” Apparently, he received “injections of musk, camphor and other substances.” In the event, Tchaikovsky’s condition had greatly improved by 3 November, and hot baths were prescribed as a possible follow-up treatment. However, by 4 November his kidneys had stopped to function properly, his diarrhea had become uncontrollable, and his condition critical.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 18 Morceaux, Op. 72 (Mikhail Pletnev, piano)

Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky

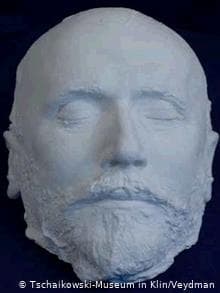

Compiling contemporary eyewitness reports, scholars assert that “throughout the day Tchaikovsky repeatedly lost consciousness and succumbed to delirium; towards the evening his pulse began to weaken and his breathing became inhibited. After ten o’clock in the evening the patient’s state was declared hopeless. Almost without attaining consciousness, as a result of oedema of the lungs and a weakening of cardiac activity, the composer passed away at fifteen minutes after three o’clock on the morning on 6 November according to the Western calendar.” Newspapers printed announcements of Tchaikovsky’s death, and his body lay in state for public viewing. The Petersburg Gazette wrote, “A transparent shroud covered the body up to the neck and only the presence near the head of someone continually touching the lips and the nostrils of the deceased with a bit of light-colored material soaked in carbolic solution reminds one of the terrible illness that struck down the deceased.” Countless visitors offered their final respects, and the composer was buried at the Tikhvin Cemetery of the Saint Aleksandr Nevsky Monastery on 9 November.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 73 (Dmitri Hvorostovsky, baritone; Ivari Ilja, piano)

Tchaikovsky’s death mask

As soon as Tchaikovsky was laid to rest, various theories of what actually killed him began to circulate. His brother Modest wrote that his brother drank unboild water, from which he contracted cholera. It was suggested that Tchaikovsky had imbibed unboild water either at his favorite restaurant or elsewhere, “as his own fateful recklessness during a cholera epidemic was self-evident.” In addition, rumors started to circulate that his doctors had failed to treat him properly.

Tchaikovsky tomb at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery

A different theory emerged by connecting his death to his 6th Symphony. The “Adagio Finale” sounded to many like a premonition of death, and it was suggested that Tchaikovsky had deliberately taken his own life by drinking contaminated water. That theory gained renewed currency in 1980 when a musicologist suggested that “Tchaikovsky died by suicide, carrying out a sentence passed by a court of honour of his classmates at the School of Jurisprudence: Tchaikovsky’s sexual advances to a young man of high birth were about to be made public, and death was nobler than bringing dishonour upon the school.” Exactly what killed the composer might never be known, as the polemics over his death have reached fever pitch in recent years. A scholar writes, “the arguments have reached an impasse, one side supporting a biographer not invariably committed to the truth, the other advocating something preposterous by the mores of the day.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 75

Excellent documentation on the subject of Peter Tchaikovsky. Being my favorite composer I have always wondered about his personal, as well as his musical, life. Many thanks for the enlightenment.