Ludwig van Beethoven, 1814

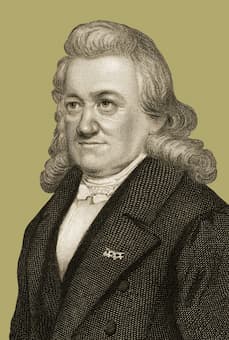

Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto—nicknamed “Emperor” after Beethoven’s death and referring to the work’s majestic character rather than a specific political figure—was conceived during troubled times. Napoleon’s forces had invaded Vienna in 1809, and the subsequent French occupation brought physical and economic chaos. On 26 July 1809 Beethoven wrote to his publisher, “What a destructive, disorderly life I see and hear around me, nothing but drums, cannons and human misery in every form.” Concurrently, his rapidly advancing deafness made public appearances all but impossible. Yet, despite this political and personal turmoil and despair Beethoven was busily working on his 5th piano concerto. His ability to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles through the sheer force of his will produced by far the most symphonic of his concertos, and it represents the summation of Beethoven’s achievements in the concerto genre. When the work premiered in Leipzig on 28 November 1811, Beethoven was substantially deaf and the honor of playing the solo part went to the young church organist Friedrich Schneider. The concerto first sounded in Vienna on 12 February 1812 with Carl Czerny as soloist, and Felix Mendelssohn played the England premiere on 24 June 1829.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73 “Allegro”

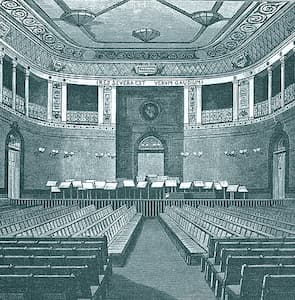

Altes Gewandhaus — Erster Konzertsaal

The music critic for the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung wrote, “There followed Beethoven’s newest concerto for the pianoforte… It was performed beautifully. This is undoubtedly one of the most original and effective of all existing concertos, one of the richest in imagination but also one of the most difficult. Music director Schneider—organist at the University Church in Leipzig, and later organist at St Thomas—played it so masterfully that we could not imagine greater perfection: certainly not in regard to dexterity, clarity, security, and delicacy, but also not in regard to soul and perfect comprehension of the meaning and intent of the composition, and certainly overall, as for every individual passage in particular. As the orchestra also accompanied the work and the soloist just as one might wish, with unmistakable attention and love toward the composer, the very large audience could hardly have failed to be moved to rapture, which they could scarcely satisfy with the customary expressions of gratitude and joy.” The reviewer was clearly delighted with his seventh concert in the Gewandhaus series, conducted by J. P. C. Schulz. Audiences and critics in Vienna were less charitable. The music critic for the newspaper Thalia writes on 19 February 1812.

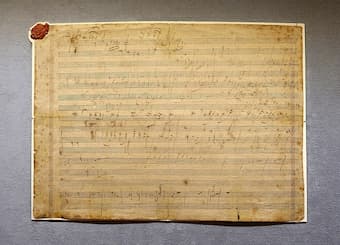

Beethoven’s sketch for the first movement of the Emperor Concerto

“If this piece of music… did not receive the applause that it deserved, the reason lies partly in the subjective character of the composer, partly in the objective attributes of the listeners. Beethoven, full of proud self-reliance, never writes for the masses; he wishes to be understood and felt, and because of the difficulties which he intentionally creates, only connoisseurs are capable of this, and an abundance of them cannot be counted on on such occasions. In the exuberance of his genius, he almost never thinks of the ne quid nimium; he pursues his theme with tireless haste, not infrequently makes digressions which seem baroque, and thus, through exertion, he himself exhausts the eager attention of the weaker musical amateur, who cannot follow his train of thought. The non-connoisseurs, however, are led by the length into chaotic night and become bored.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73 “Adagio” (Hyo Joo Lee, piano; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Douglas Boyd, cond.)

Friedrich Schneider

The Viennese reviewer was seemingly startled not only by the concert’s lengths, but also by its unique features. The opening “Allegro” features a most unusual and extraordinary beginning, as orchestral chords punctuate a fully written-out solo cadenza. The orchestra finally enters with a military theme of harmonic simplicity, contrasted by a secondary thematic idea that transforms and transports its original rhythmic angularity into a distant tonal realm. A blindingly brilliant solo part permeates much of the musical discourse, and Beethoven, assuming total control over every aspect of the composition, provides the soloist with a fully notated cadenza at the end of the movement. Improvisatory and reaching for distant and unexpected keys, the muted “Adagio” creates an irresistible sense of yearning. A devotional orchestral opening is answered by an expressive and highly lyrical theme in the piano, and after a sudden and unexpected harmonic shift, the soloist quietly introduces fragments of the principle theme of the “Rondo” finale. Instead of retaining the character of the main theme throughout, Beethoven consciously subdues this exuberant melody before it blazingly returns in its original form. Adding a touch of suspense, the solo piano and the solo timpani combine in an unlikely duet before Beethoven’s most formidable and compelling concerto come to a rousing close.

Apparently, Beethoven’s “Emperor” was the favorite concerto of Franz Liszt, who performed it on numerous occasions, including at the unveiling of the Beethoven Monument in 1845.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73 “Rondo”

Who are the performers in the 1st movement? The Youth orchestra plays beautifully. The pianist? Ehhh. Thank you,