Water Mill

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) took up the story of the beautiful miller’s daughter in 1823 using selections from a longer poem published in 1820 by his friend Wilhelm Müller. Müller’s original poem is made up of some 25 separate poems, only 20 of which were set by Schubert. In the prologue to the poem, the poet apologizes for his work, calling it a ‘monodrama.’ There’s only one character as ‘a river does not actually count as a character’.

Schubert picks up the tale in the 2nd poem, ‘Wandering,’ where we meet our hero, described in the prologue as a ‘young, blond miller’s lad.’ He’s wandering the countryside in spring as a journeyman miller, looking for a position after having completed his training.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 1. Das Wandern (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

Flowers along a brook

What we get from this setting is the essential simplicity of our unnamed hero. The piano takes on the role of the river, the water, the wheel, the mill stones, and, finally the weight of his responsibility as he must stop wandering and buckle down to work. All of the elements of his new job are in the piano part.

The next songs are all to the brook, and in song 4, he offers thanks to the brook for bringing him to the mill, and, more importantly, to the miller’s daughter. Now the music slows and we see the less-impetuous side of our hero – he’s seen her! His work will bring him all he wants in life, including her.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 4. Danksagung an den Bach (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

Now, of course, he has to try to move the very elements to get her attention, but he’s still seen as just one of the boys who work for her father. Even without any encouragement from her, he’s now asking the flowers, the stars, and finally the brook if she loves him. No answer. Next, he wants to tell the world of his love, but not her, because she should be able to read from his eyes.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 7. Ungeduld (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

Ah, then we find he’s made himself a bit too obnoxious – when she meets him in the morning, she avoids his gaze, avoids his presence, and he is left bewildered. So, he will leave invisible notes for her- flowers under her window that will convey his love, being the visible forget-me-nots of his desire. He meets her down by the brook where they sit and watch the water together before she leaves him with the words “Rain is coming. Bye! I’m going home.” And with those words, he knows that she is his.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 11. Mein! (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

The brook

And now we know we are in his world of self-deception and illusion. She’s done nothing to encourage his attentions, which she probably gets every time there’s a new boy at the mill, except to be polite and he’s taken that as the key to her heart.

Now come two songs to his lute, one describing how he’s wound a green ribbon around the lute, but can’t pick the lute up because he’s so full of longing, he can’t move past his love pain to create new songs. Then he chooses to send her the green ribbon from its lute so that it won’t fade but will show her how ‘their’ love is evergreen. When she wears it, he will know his love is returned.

Next, the rival turns up. And worse, he’s not another miller so that our hero can compete with him fairly, he’s a hunter! The miller thinks he’s too noisy, with his gun, his horn, his hounds and will frighten away the ‘gentle doe’ he loves. Our miller is frantic with worry.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 14. Der Jäger (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

He’s lost – she’s been at the gate looking for the hunter, not down by the brook with the miller. He complains to the brook. His beloved green is now the symbol of death for the miller – the green of the weeping willows, the green of a concealing thicket – because he’s hunting Death.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 16. Die liebe farbe (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

As our miller turns away from life – symbolized by the fact that all green is anathema to him and has become a hated colour – even the flowers that brought him such joy are now faded and wilting. The seasons change and the flowers die, and with them, his message of love to her, but they will return in the spring to reproach her.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 18. Trockne Blumen (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

Now the miller turns back to his one friend who has been with him since the start of his journey in springtime, the brook. But what is he asking his friend to do for him – not to take him away from this hated place to a new mill, but to take him away entirely. They tell each other fantasies – when a true heart dies the lilies wither, the moon and angels are filled with tears, The brook tell him of impossibilities – a new love means a new star, flowers bloom and never wither, and angels appear on earth every morning.

Finally, he dies in the stream and the brook becomes his belated defender from the eyes of the hunter and the faithless miller’s daughter. The brook sings a lullaby as he takes the miller to his final sleep.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25, D. 795 – No. 20. Das Baches Wiegenlied (Andrè Schuen, baritone; Daniel Heide, piano)

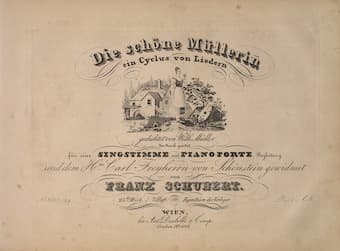

Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin Diabelli Edition

This is the full Romantic life in a song cycle – emotions are on edge, reactions are outsized, and refusal of love can only mean that the lover dies. In Müller’s original, the poet of the prologue returns in an epilogue, following what he calls the brook’s ‘funeral speech’ with his own call to memory – if you want to dream an easy dream, then dream of the mill and the water, but a long night will mean you dream of the miller and asks that you give him love for his suffering.

In giving this a modern reading, we can reexamine the miller as an incel, desiring but unable to find a willing partner. We also can look at this from the woman’s point of view. No mention is made of her desires except to belittle them. How can she want a hunter when there’s this nice miller right here? Why should she want to get away from the incessant sound of the mill to the quiet of the forest where the hunter lives? Why indeed?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Last time I listened to “Die Schoene Muellerin” was about forty years ago. The experience was so painful, I never listened to it again. Except just now–the hauntingly lovely “Song of the Brook.” And, reading your synopsis, I suppose you could say: that brook was the poor guy’s evil genius. Luring him on to the lovely young woman–luring him on to inevitable heartbreak–luring him on (finally) to take his own life. I cannot but think of this as a massive, irreparable failure on the young man’s part. How can death possibly heal the wounds of life? We simply carry them on into the grave. Like wretched Queen Dido in Virgil. “Vixi et quem dederat cursum fortuna peregi.” “I have lived and finished the course given me by chance.” Well–an unforgettable masterpiece nonetheless. Thank you.

Thank you for this essay which I found very helpful in understanding this overheated tale, whose music is so good.

By chance, have you a text copy of the epilogue either German, or in English translation? I have recited the prologue in an early recital I performed at Stanford University in the mid 70s, but have not read the epilogue!

Thanks

The Epilogue in German and the other verses that Schubert didn’t set can be found here:

Epilogue: https://www.lieder.net/lieder/get_text.html?TextId=12665

The whole poem and who set which verse: https://www.lieder.net/lieder/show_poems_in_group.html?CID=1176

According to the LiederNet Archive, no composer they know of has set the Epilogue.

Müller’s poem comes from a collection entitled Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten (Poems from the papers left behind by a traveling French horn player), published in two volumes, 1821–1824.