Franz von Lenbach: Pope Leo XIII

Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904) was one of the most accomplished portrait artists in German art of the 19th century. As one of the leading exponents of 19th century realism in Germany, he was the best-known and highest-paid portrait painter of his day. His clients included royalty, popes, cardinals, nobles, military leaders, artists and businessmen.

Franz von Lenbach: Otto von Bismarck

We find portraits of Emperor Wilhelm I, Otto von Bismarck, whom he painted about 80 times, William Gladstone, Pope Leo XIII, Emperor Franz-Joseph I, Princess Clementine of Coburg among countless others. His true-to-life paintings display a great virtuosity of technique, and his work attracted significant interest in the world of music. After all, he painted powerful and famous portraits of Richard Wagner, Franz Liszt, Johann Strauss, Edvard Grieg, and Clara Schumann.

Clara Schumann: Piano Trio in G-minor, Op. 17

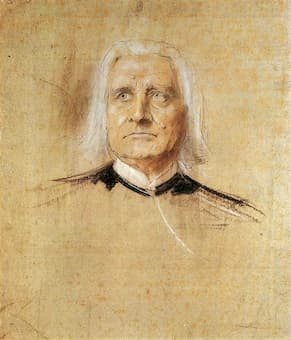

Franz von Lenbach: Franz Liszt

Lenbach was born on 13 December 1836 in Schrobenhausen and initially trained in his father’s workshop to become a stonemason. He worked as an apprentice in the Munich workshop of sculptor Anselm Sickinger, and overcoming opposition from his father, he studied for two semesters at the Augsburg University of Applied Sciences. After entering the Munich Academy of Fine Arts in 1854, Lenbach became a student of the eminent history painter Karl Piloty. Lenbach produced his first important works, and his initial exhibition in 1858 sold a number of works.

Franz von Lenbach: Franz Liszt (1884)

He also won a travel scholarship, which allowed him to accompany Piloty to Rome. He produced countless landscape pencil drawings, which he subsequently uses as the basis for oil paintings. Upon his return to Munich, Lenbach was offered the post of professor at the newly established Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School. He held that position for only two years, because Baron Friedrich von Schack commissioned him to copy a number of masterpieces in some of the best art museums in Europe. Between 1863 and 1868 Lenbach visited Italy and Spain copying the Old Masters.

Richard Wagner: “Prelude to Act 1” of Die Meistersinger

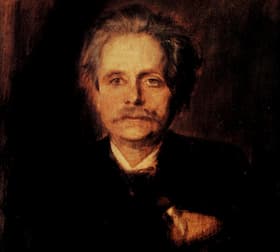

Franz von Lenbach: Richard Wagner

During a visit to Tangiers in 1868 Lenbach painted his last landscapes, and he subsequently devoted himself exclusively to portraiture. One of his early clients was none other than Richard Wagner. Scholars have suggested that in the late 1870s, “Lenbach rethought the concept of portraiture, reviewed his past practices, and created a new method of portrait painting that led to some of his most interesting works in this genre.” Although he had asked clients to pose for preliminary drawings or oil sketches, he did not complete his portraits with the sitter posing in the studio.

Franz von Lenbach: Richard Wagner

He reasoned “all too often sitters fell into stereotypical poses, and that it was impossible to bring out the character of a sitter frozen in a single pose for an entire sitting.” Lenbach had the ability to keenly observe and analyze anatomical forms. He told a biographer, “Even then I noticed that I had uncommonly little imagination and could remember only one thing: the organic logic of nature, if I may be allowed to put it that way. I could see, for instance, how a specific person’s ear emerged out of his head and once I had seen that, it stuck with me as an organic inevitability and it appeared before my eyes whenever I thought of it.”

Edvard Grieg: Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 (Dmitry Sitkovetsky, violin; Bella Davidovich, piano)

Franz von Lenbach: Edvard Grieg

A scholar writes, “Lenbach’s interest went beyond merely copying the head in all its structural and surface details; he wished to capture a characteristic expression of the sitter.” In order to achieve this goal, Lenbach eliminated the atelier pose “in favor of the artist’s observation of the model seated informally and even moving slightly around the studio… Photography began to play a major role.” Lenbach regularly hired professional photographers, and he described his new method as follows.

Franz von Lenbach: Clara Schumann (1878)

“Once I have drawn the figure from life (and I always do that first) and I have had the movement photographed, it becomes a matter of fleshing it out with the help of photography and the imagination.”

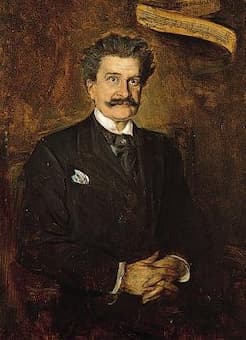

Franz von Lenbach: Johann Strauss

It has been suggested “what distinguished Lenbach’s method was not the production of portraits with the aid of sketches and photographs but his use of photographs of movement and his decision to ‘flesh out’ these photographs rather than slavishly copy them.” Pope Leo XIII might actually have inspired this new technique, since the Holy See had no time to sit for the portrait. Lenbach visited Egypt in 1875/76, and eventually he was made a Knight of the Bavarian Crown. In a good many of his portraits Lenbach claimed the artist’s independence from aristocratic culture, and in his composers portraits he had the uncanny ability to see well beyond the anatomical surfaces.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Valse oublieé No. 1