Johann Sebastian Bach: Magnificat in E-flat Major, BWV 243a

The Church of St. Nicholas in Leipzig, 1749

The church of St. Nicholas in Leipzig is named after the patron of travelers and merchants. Construction began around 1165, and originally the church featured twin towers. It was extended and enlarged in the early 16th century, and the Baroque main tower was added in 1730. Only 7 years earlier, on 30 May 1723, Johann Sebastian Bach began his duties in Leipzig. Although St. Nicholas was regarded as Leipzig’s main parish church, it had its own organist, but no cantor. Bach was employed as cantor of the neighboring St. Thomas and director of music in Leipzig. As such, he was responsible for the church music at St. Thomas and St. Nicholas, as well as the church of St. Matthäi and St. Peter. Over the years, St. Nicholas witnessed the premieres of a number of Bach compositions, including the St. John Passion in 1724 and the Christmas Oratorio in 1734/35. On 25 December 1723 Bach premiered his Magnificat in E-flat Major, BWV 243a—his musical setting of the Latin text of Mary’s canticle from the Gospel of Luke—with the insertion of four seasonal movements.

Magnificat

“Magnificat,” is the hymn of praise by Mary, the mother of Jesus, found in the Gospel of Luke. It is also called the “Canticle of Mary,” and in the scripture the hymn is found after the “jubilant meeting of Mary, pregnant with Jesus, and her relative Elizabeth, pregnant with St. John the Baptist.” The Magnificat was incorporated into the liturgical services of the Western churches at vespers, and of the Eastern Orthodox churches at the morning services. The name derives from the words of the first line in Latin, “Magnificat anima mea Dominum,” or “My soul magnifies the Lord.” The Magnificat was a regular part of Sunday services in Leipzig. On ordinary Sundays it was sung in German, but for the high holidays of Christmas, Easter and Pentecost, and on the three Marian feats of Annunciation, Visitations and Purification, it was sung in Latin.

Magnificat anima mea Dominum;

et exultavit spiritus meus in Deo salutari meo,

quia respexit humilitatem ancillae suae; ecce enim

ex hoc beatam me dicent omnes generations.

Quia fecit mihi magna qui potens est,

et sanctum nomen eius,

et misericordia eius in progenies timentibus eum.

Fecit potentiam in brachio suo;

dispersit superbos mente cordis sui.

Deposuit potentes de sede, et exaltavit humiles.

Esurientes implevit bonis, et divites dimisit inanes.

Suscepit Israhel, puerum suum, memorari misericordiae suae.

Sicut locutus est ad patres nostros,

Abraham et semini eius in saecula.

Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto,

sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper:

et in Saecula saeculorum. Amen.

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord,

my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for He has looked with favor on His humble servant.

From this day all generations will call me blessed,

the Almighty has done great things for me,

and holy is His Name.

He has mercy on those who fear Him

in every generation.

He has shown the strength of his arm,

He has scattered the proud in their conceit.

He has cast down the mighty from their thrones,

and has lifted up the humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things,

and the rich He has sent away empty.

He has come to the help of His servant Israel

for He has remembered his promise of mercy,

the promise He made to our fathers,

to Abraham and his children for ever.

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit,

as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever.

Amen, Alleluia.

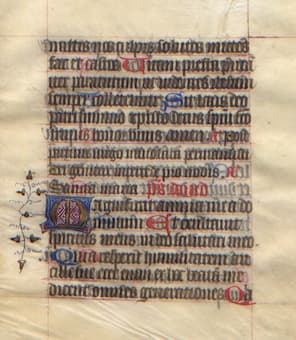

“The Magnificat” from a 15th Century Book of Hours

Bach did compose the Magnificat in 1723, his first year as Thomaskantor in Leipzig. Bach clearly understood from an earlier visit to Leipzig in 1714, that compared to Lutheran practices elsewhere, church services in town relied on an uncharacteristic large amount of Latin. As such, it was his first work on a Latin text and his first five-part choral setting in Leipzig. As is well known that Bach had a rather difficult time securing the position as Thomaskantor. Initially, the city council offered the position to Georg Friedrich Telemann, who withdrew his nomination. Next in line was Christoph Graupner, who composed a Magnificat as his audition piece, and he got the job. However, his employer refused to release Graupner from his services, and Bach was finally given the position. There can be no doubt that Bach pulled out all the stops in his setting of the Magnificat in order to impress his new employers.

Recently, scholars have been debating whether the work might have received its first performance at the Feast of the Visitation on 2 July 1723, “just five weeks after Bach took up the Leipzig post.” While this supposition cannot be entirely discounted, we are pretty certain that the Magnificat with the four Christmas interpolations—songs of praise related to Christmas, partly in German, partly in Latin—sounded in a vespers service on 25 December 1723 at St. Nikolai.

The Church of St. Nicholas in Leipzig

Bach structured the text in eleven movements for the canticle, and concluded with a doxology movement. For the most part, each verse of the canticle is assigned to one movement, and the four Christmas hymn movements are placed after the second, fifth, seventh and ninth movement of the Magnificat text. Choral movements are evenly distributed, and obbligato instruments, strings or continuo accompany movements for one to three solo voices. Contrary to typical cantatas on Baroque poetry, the Magnificat does not contain da capo arias.

The opening movement chorus is introduced by a brilliant, fanfare-like ritornello. Once the chorus enters, the music provides an image of all humanity raising their voices in praise. The word “Magnificat” dominates the entire movement, and the orchestra concludes the movement with a shortened version of the opening ritornello. This most vivid choral opening is followed by the soprano aria “Et exultavit spiritus meus” representing a personal celebration. “The voice and instrument share the musical material in a “contemplative duet,” that has been likened to an “internalized dialogue.”

The surviving autograph score now calls for the insertion of the first Christmas interpolation. Apparently, inserting four hymns in the Magnificat for the Christmas vespers had a long tradition in Leipzig. “From heaven on high I come” is the first stanza of a hymn by Martin Luther, and it paraphrases the Annunciation to the shepherds. Bach sets the text as an a-capella motet, with the soprano voices singing the chorale tune in long notes.

Domenico Ghirlandaio: Visitation

“Quia respexit humiltatem” is scored for soprano and obbligato oboe. A leading conductor writes, “humility is a downward gesture, and so everything takes a long, s-shaped movement downwards, with just a little rise at the end. The use of limited resources of one wind instrument provides this movement with decidedly subservient feel.” This internalized dialogue bursts into the choral “Omnes generations.” This is a typical crowd movement we know from Bach’s Passions, with the fugue following the stretto principle from the very beginning.

“Quia fecit mihi magna” is a bass aria accompanied only by the continuo. God’s might is presented in the bass voice, and the ritornello of a downward leap and downward scale is repeated throughout the movement. The second Christmas interpolation “Rejoice and celebrate” is set for pairs of voices in parallel motion and supported by an independent basso continuo. Violins softly undulate in “Et misericordia a progenie in progenies,” to introduce a tender duet between alto and tenor. This movement has been compared to the pastoral sinfonia at the beginning of Part II of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, “creating a romantic, soft-edged, almost comforting sound… full of pathos with the divine quality of mercy expressed in beatific parallel thirds of the violins in the ritornello.”

The fugue in “Fecit potentiam” represents a highly graphic and dramatic portrayal of the words “he has scattered,” clothed in wonderful harmonies. Supposedly, the trumpets “play their highest available notes as an image of “rich people’s hearts, who have been misled by worldly promises.” The third Christmas interpolation “Glory to God in the highest” sets a text from the Christmas story in chordal fashion.

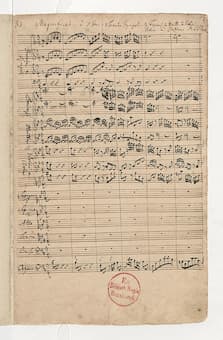

J. S. Bach, autograph of the Magnificat in D Major, BWV 243. First page of the first movement “Coro”

The powerful aria “Deposuit potentes” (He has brought down the powerful) is scored for tenor accompanied by only the violin and continuo. Accompanied by two recorders, which may symbolize the need of the hungry, “Esurentes implevit bonis” is followed by the fourth Christmas interpolation “Virga Jesse floruit.” This duet for soprano and bass appears incomplete in the original manuscript, but since Bach used the music again for a Christmas cantata two years later, the missing parts could be reconstructed.

Scored for the unusual combination of the three highest voices, violins and violas in unison and trumpet, “He has helped his servant Israel” the cantus firmus is played by the trumpet, and the “unison strings symbolizes the divine quality of mercy.” The second musical idea is a disjunct theme, with Bach repeating the figure by the falling interval of a fourth on each syllable, possibly interpreting this motif as a symbol of the cross.

Written in stile antico, the strict fugue in “Sicut locutus est ad patres nostros” alludes to Bach’s musical forefathers, “with four measures followed by four measures, with each voice coming in predictably and on time, all according to the rulebook, unimaginative and extremely dull.” The movement ends with a more homophonic section in which the bass has the theme once more, while the soprano sings long suspended notes covering almost an octave.

The Magnificat concludes with the doxology performed by the ensemble in two parts. The first part addressed the Trinity, with the “Gloria” sounded three times. The second part, “Sicut erat in principio” repeats material from the beginning of the work but shortened, as a frame. Some ten years later, and possibly written for the Visitation service in 1733, Bach produced a new version of the Magnificat. This version, which has gained greater popularity, is transposed to D major. However, several elements of the early version were lost in the process of re-writing. “Recorders, rather than the transverse flutes of the later version, accompany the ‘Esurientes’; a trumpet, rather than oboe, played the tonus peregrinus melody of the ‘Suscepit Israel’, and, at certain points in the earlier version, the harmonies are rather more pungent (e.g. the fermata chord just before the end of the chorus ‘Omnes generationes’).”

“The difference in key also affects the layout of the string parts, in particular; this is most noticeable in the ‘Deposuit potentes’, where the opening scale is an octave lower in the violins and the open G string (the key note for this aria), the lowest note of the violin, is suitably employed. The triplet passages that appear three times between the block chord passages of the ‘Gloria’ were originally written without the sustained continuo notes that Bach added to the later version. These latter undoubtedly make the passages easier to sing, but the early version is arguably more exciting in the way that the vocalists are encouraged to direct their lines towards the next tutti passages.” It was not uncommon for Bach to recast or update his compositions, but whatever version of the Magnificat you prefer, “the extraordinary impact of Bach’s great choral works derives essentially from his remarkable ability to balance, yet at the same time to exploit to the full, the spiritual and dramatic elements of the text.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter