Maurice Ravel, 1925

In the early morning hours of 28 December 1937, Maurice Ravel lapsed into a coma and died aged 62. The composer had entered a clinic on rue Boileau in Paris for neurological tests. In the event, exploratory brain surgery—apparently without adequate anesthetic—was performed on 20 December 1937. The neurosurgeon Clovis Vincent “exposed the right frontal bone flap revealing a slack brain without actual softening in the area displays. An attempt was made to inflate the right lateral ventricle with 20cc saline solution, but it did not succeed despite repeated attempts. No tumor was found and no biopsy was taken.” Ravel briefly regained a minimal level of consciousness, “but unable to swallow or take nourishment he lapsed into a coma and died.” Ravel had been troubled by persistent health problems for some time, suffering from insomnia, extensive bouts of depression and difficulties with coordination. Ravel’s brother Edouard began to suspect a neurological cause and even feared that Maurice might have a hidden tumor.

Maurice Ravel: Concerto for Piano left Hand

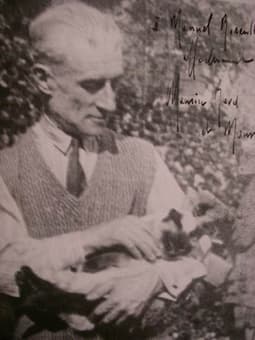

Ravel and his cat

By 1927, Ravel’s health had significantly deteriorated and his symptoms grew more alarming. He started to have difficulties speaking and could no longer completely rely on his motor skills. He would grasp the fork by the wrong end, and was unable to sign his name. Rather alarmingly, he also had difficulties playing the piano. While he could still hear and compose music in his head, he lost the ability to write it down. “My mind is full of ideas,” he reported, “but when I want to write them down, they vanish.” In 1932, Ravel was injured in a taxi accident. He lost a couple of teeth and suffered a mild concussion, and possibly experienced whiplash. After receiving acupuncture treatment and hypnosis, Ravel seemingly recovered from his injuries. However, it has been suggested that the accident exacerbated an already existing brain disease, or alternately, cause more neurological damage than was at first suspected. He did accept a commission to write music for a film about Don Quixote, but it took him the better part of a year to finish the three songs of Don Quichotte à Dulcinée. It was to be his last completed work.

Maurice Ravel: Don Quichotte à Dulcinée

Ravel on his deathbed © Lebrecht Music & Arts

Ravel had always been a strong swimmer, but during an early summer holiday in St. Jean-de-Luz in 1933, he found himself in mortal danger. Unable to coordinate his movements he had to be rescued from the water. By 1934 his health had deteriorated further, and it took him an entire week to write a letter of condolence to a friend on the loss of his mother. It has been reported that he had to frequently consult the dictionary to remind himself how the letters of the alphabet looked. His housekeeper used to pin his address inside his coat when Ravel went out to dinner. On one occasion, Ravel supervised a recording of his string quartet. He sat in the control room and offered various suggestions and corrections. After each movement had been recorded, he was apparently asked if he wanted to listen through it again, but he declined. In that way, the recording session was completed in record time. At the end of that session, Ravel turned to the producer and said, “That was really very good. Remind me of the composer’s name.” On a different occasion, Ravel went to a concert featuring his piano works. He rather enjoyed the performance, and when the hall turned to acclaim him, “he thought they were addressing the Italian colleague at his side, and so joined in their applause.” It was becoming patently clear to everybody involved that things could not continue in this way, and Ravel was placed in the clinic on rue Boileau.

Maurice Ravel: String Quartet in F Major

Ravel’s grave

Scholars are still hotly debating the exact cause of Ravel’s death, and whether his neurological problems had a direct impact on his compositions. One train of thought suggests that Ravel might have suffered from a degenerative disease of the brain called “Pick’s Disease,” a rare neurodegenerative disease that causes progressive destruction of nerve cells in the brain. Others believe that Ravel’s illness belonged to a group of cerebral atrophies accompanied by ventricular enlargement. This has led to speculation that Ravel had undergone a procedure called “pneumoencephalography,” which drains the cerebrospinal fluid from around the brain and replaces it with oxygen or helium to allow the structure of the brain to be imaged on X-ray film. Since no radiologic films or reports have been discovered, it is still unclear whether Ravel had undergone this procedure. At any rate, there is a growing body of literature attempting to discover signs of Ravel’s neurological decline in his later compositions. It is believed that Boléro might be read as “a pure form of musical obsession… and that it mirrors the symptoms of the underlying neurological disease; a beautiful symptom of a terrible disease.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: Boléro