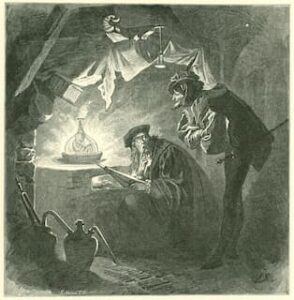

Anton Kaulbach: Faust und Mephisto

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) always envisioned a national German opera that presented a complete union of text and music with a plot based upon a supernatural and mythical German legend. As he confessed to a friend in 1842, “Do you know my daily prayer as an artist? It is German opera.” Schumann’s principle aim was to raise dramatic music to the high standards of the German literary culture, and he originally contemplated an opera based on Goethe’s Faust. Daunted by the expansiveness of the subject he eventually shaped the narrative in the manner of a secular oratorio.

Faust I, first edition, 1808

For Schumann, “there was only one way of doing justice to Faust, and that meant to select only a few intense and symbolic moments to be set to music.” By omitting vital parts of the Faust legend and setting only selected scenes to music Schumann assumed that his audience would be familiar with the Goethe text. However, Schumann himself was intimidated by the idea of setting Goethe’s text to music, as he wrote to Franz Brendel, “what is the point of writing music to poetry that’s so perfect.” In addition, looking to depict the psychological emotions of various characters in dramatic situations required a multitude of soloists, orchestra, and choir, and Schumann clearly understood that he was facing a rather difficult task.

Robert Schumann: Scenes from Goethe’s Faust – Overture (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

Goethe’s Faust

In a letter to Felix Mendelssohn from 24 September 1845, he writes, “The scene from Faust lies in my desk drawer; I am really anxious to take another look at it. What gave me the courage to tackle the subject in the first place was the moving, sublime poetry of the conclusion. I don’t know whether I’ll ever publish it.” At this time, Schumann believed that he had completed the Faust project, when in fact he had only scored the third section of the work, Faust’s Transfiguration. Over the next nine years, Schumann added and extended his composition, adding the famous “Chorus Mysticus” in 1847. He appended the first section, including the “Garden Scene” and “Scene in the Cathedral” in 1849, and “Faust’s Death,” representing part of the second scene, was added in 1850. Finally, he added the overture in 1853. The partly finished work was performed as part of the centennial celebrations of Goethe’s birth in 1849 in Dresden, Weimar and Leipzig. The work was well received, and Schumann commented, “What gave me the greatest pleasure was to hear from many people that the music had made the meaning of Goethe’s text clear to them for the first time.”

Robert Schumann: Scenes from Goethe’s Faust – Part II: VI. Fausts Tod (Alastair Miles, bass; Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Netherlands Radio Choir; Netherlands Children’s Choir; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

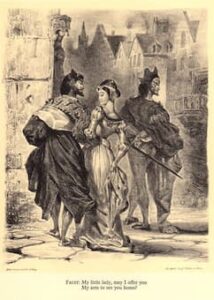

Faust and Gretchen in the Garden

Schumann sadly died in 1856, and he was never able to hear a performance of the full work. The completed Scenes from Goethe’s Faust received its premiere in Cologne, under the direction of Schumann’s close friend Ferdinand Hiller on 13 January 1862. “It is this version that we know today, with all its revision and additions, its disjointed narrative flow, and its moments of intense beauty and power.” Schumann’s music suggests the struggle between good and evil at the heart of Goethe’s work, as well as Faust’s tumultuous search for enlightenment and peace.

Delacroix: Illustrations for Goethe’s Faust

In the first part, a tense and tempestuous overture is followed by an operatic love duet and passionate aria depicting the story of Gretchen’s seduction, ending with the “Church Scene.” The second part presents the contrast between Faust’s enjoyments of the beauties of nature set against his philosophical struggles of finding meaning upon hearing of the creation of a new and everlasting world. Schumann’s highly Romantic music immerges us into the world of the supernatural, as this part ends with Faust’s death. The final scene, Faust’s transfiguration, contains some of “Schumann’s most effective choral writing,” as the work draws to an unsettled conclusion in the “Chorus Mysticus.” Schumann’s Scenes from Faust is once again considered to be among his most moving works. “It stands at the pinnacle of his Romantic concern with extra-musical, and especially the literary potential of musical expression.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Robert Schumann: Scenes from Goethe’s Faust – Part III. VII. Fausts Verklarung: Dir, der Unberuhrbaren (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Mojca Erdmann, soprano; Elisabeth von Magnus, alto; Christiane Iven, mezzo-soprano; Birgit Remmert, alto; Netherlands Radio Choir; Netherlands Children’s Choir; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)