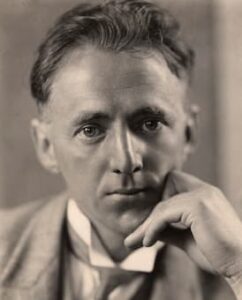

Arnold Bax

With a title that sounds rather like a children’s story, The Happy Forest by Arnold Bax (1883-1953) sprang from a prose poem by the British theatrical writer Herbert Farjeon. This appeared in the quarterly magazine Orpheus, which was edited by Clifford Bax, Arnold’s younger brother.

Clifford Bax, incidentally, was an important spark for other musical pieces: he was the one to suggest to Gustav Holst the subject of The Planets, for example.

Herbert Farjeon (University of Bristol Theatre Collection)

Very much in an idyllic style, Farjeon’s prose poem evokes the rustic world of galant shepherds and satyrs. Bax’ work was first written as a piano piece in 1914 and then was orchestrated in 1921. Bax’ biographer notes the dates of the two versions – and the fact that the first world war came between them. If the piano piece was just a setting of the poem’s ideas, the orchestral work was an image of a truly lost world.

Clifford Bax (1922) (London: National Portrait Gallery)

The evocation of an Arcadian pastoral world opens with our storyteller lying ‘…in a green place of the forest …’. He sees, but they don’t see him, two shepherds who ‘…spoke in rhyme like poets…’ competing in verse to praise their beloveds. It’s a scene straight out of Virgil. They are joined by a young satyr who dances with all the joy of spring in his step (‘kicking his legs in such infectious mirth that I was constrained to stuff my mouth with grass, least they should hear…’). A new arrival, a third shepherd, awards the victor’s garland to one of the competitors and plays his pipe. The shepherds, the satyr and our poet stay there all day; as the moon rises, the shepherds are all seen far on the rim of the hill, led by the satyr, still dancing.

Jean Raoux (1677-1734), La Danse (1728)

Farjeon could be writing a scene to match Mallarmé and his faun that Debussy used as inspiration for his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894). This satyr, however, has shepherd friends and that addition brings the story closer to us than the mythic being in Mallarmé’s poem.

The Happy Forest, along with his tone poems The Garden of Fand, November Woods, and Tintagel, established Bax as a British composer. The rhythms are light and dance-like, with skillful use of the percussion section (tambourine and xylophone) to help evoke the movement of the shepherds and the satyr. In the middle (3:30), Bax lets loose his romantic side, giving us a section where the strings are given the freedom with a theme of power and love. As the shepherds declaim their poetry to their beloveds, Bax imbues the strings with a loving melody, underscored with comments (could that be the satyr’s cynicism?) in the winds. At the end, they all dance off into the moonlight.

Arnold Bax: The Happy Forest (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; David Lloyd-Jones, cond.)

Jacob Jordaens: A Satyr (ca. 1630) (Rijksmuseum)

Bax doesn’t give us the story line for line – he was known, as one writer said, for keeping ‘all his programs veiled behind a late-Romantic haze.’ We know his inspiration and at the same time, we are free to make up our own story to Bax’ ever-shifting soundscape. He gives us the natural landscape but peoples it with creatures of long-past history and then leaves us free to fill in the details.

There’s no recording of the piano version but the orchestral version is one that most critics agree represents the world of the past, the world before the war. The piano piece is dedicated to Farjeon and the orchestral version to Eugene Goossens, who conducted the premiere in July 1923.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter