© Vox Media

For musicians, trading off stories about conductors is the water-cooler-iest form of water cooler gossip. Tales of incompetence abound, and those who are lucky enough to gain approval are spoken of with respect and appreciation.

To an audience, conducting seems to be mostly hand-waving (amongst other things: if you’ve ever been unlucky enough to get caught in the crossfire of a conductor’s gyrating hips, you’ll know what I’m talking about) – but beyond the physical gestures (whatever they may be), every conductor has their own unique style, made up of many things beside their baton technique. What makes a good or bad conductor in the eyes of a musician depends on almost as many things as there are musicians on stage.

We’ve already seen that the basics of conducting involve simple beat patterns that are universally understood by musicians. However, in developing their own ‘personal styles’, some conductors start to take liberties with these patterns, and in the quest for expressive meaning, sometimes end up (now, how do I say this politely), erm, straying quite far from the norm?

It’s totally fine to deviate from a simple beat pattern if what you communicate is still clear and understandable. We all know the old adage: learn the rules first, then break them. It takes a conductor of great skill to do their own thing and still remain intelligible. Sometimes the conductor is up on the podium throwing some shapes that probably look wonderful to the audience behind them, but make no sense whatsoever to the musicians on stage. It then becomes a case of ‘heads down’, using only our ears to stay together and only looking up at crucial moments.

As you can imagine, it’s not exactly fulfilling to play music with an attitude that amounts to little more than damage limitation. We want to have the freedom to be creative, but also need support in the right places, and if it sounds like a tricky balance, that’s because it is. Conducting is a little like chess, or Tetris, or being in at the right time for a home delivery: easy to understand, difficult to master. It is precisely because it is all about knowing when to step in and when to stand back that makes conducting such a challenge: go too heavy and the musicians feel straightjacketed; not enough support and the performance risks falling to pieces.

Dvořák: Symphony No. 8 – Anna-Maria Helsing – Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Anna-Maria Helsing, a conductor of great skill, keeps the pulse going while showing a whole range of expressive emotion in the opening of Dvořák’s 8th Symphony.

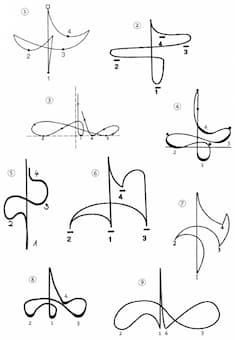

A selection of beat patterns from different conductors

© Morten Schuldt-Jensen/Signata

It’s a fine line to tread, and only a handful do it successfully. Of course, every musician has their preference when it comes down to the details (and I can only speak from my opinion), but by and large, it’s easy to tell when you’re being supported as opposed to controlled. A big contributor to this is the attitude of the conductor in rehearsal – how a conductor rehearses can have a big impact on how the orchestra plays.

Orchestras spend much more of their time rehearsing than performing, and it is during this time that the relationship between the group and its director grows. It’s like any other business setting: if your boss is badly prepared, does not listen, is authoritative, defensive and power hungry, you are hardly going to want to do a good job. On the other hand, if you feel supported, listened to, encouraged and valued, then you naturally try harder, often without even realising.

I’d like to emphasise at this point that orchestras never try to deliberately play badly if they’re having a hard time with the conductor. We are all there to play music and try our best to create something special, and if we don’t get a lot of support from the podium, that’s just life. With a bad conductor, the base line will still be an enjoyable performance – it’s just that the best conductors take it to the next level. Audiences ideally shouldn’t notice the nuances of conductor-orchestra relationships – it’s our job to bring music to you, not to highlight a difficult working environment.

Candide – What the orchestra sees or “The dancing conductor”

One of my personal favourites – the dancing conductor. Not generally recommended unless you have the complete trust of the orchestra!

Very few conductors are so incompetent that the performance will literally fall apart at their hands – orchestras have plenty of tricks up their sleeves to keep the show going – but the nature of conducting goes so far beyond the simple waving of hands. Look at the faces of the musicians on stage next time you go to see a concert. Are they always looking up from their music? Does their playing have a special energy? Are they moving together, glancing across their sections, catching someone’s eye and sharing a quick smile? If so, they may be in the hands of a good conductor – no hip thrusting in sight…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Look Ma No Hands! Leonard Bernstein at his best…

Bernstein deviating from a beat pattern by, erm, not using his arms at all.