Peter Paul Rubens: Prometheus Bound

Prometheus, so it is told in Greek mythology, gave humanity the gift of fire. That creative spark gave humankind the ability to run its own affairs, and it awoke a consciousness that once only belonged to the gods. Human were now in charge of their own destinies, relying on courage, cunning, ambition, speed and strength to perform incredible deeds, battle fierce monsters and establish great cultures that changed and shaped the world. This success story doesn’t end well for Prometheus, however. Since he stole the divine fire from the heavens and passed it on to mere mortals, almighty Zeus and his sister-wife Hera devised a most cruel and terrible punishment. Prometheus is shackled to the side of a mountain, and a giant bird of prey rips open his side and feasts on his liver. Since Prometheus is immortal, his liver regenerates overnight. As such, he has to endure this horrible torment every day for eternity. This story of creation originally told by the ancient Greeks sets in motion a vast body of myths that extensively influenced nearly all aspects of Western civilization, including culture, arts, literature, religious and political considerations, and of course music. In this little series we shall explore the musical side of Greek mythology, and in the process we might just discover a contemporary significance and relevance in these themes.

Ludwig van Beethoven: The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43 (Melbourne Symphony Orchestra; Michael Halász, cond.)

Annibale Carracci: The Choice of Hercules

Heracles was the son of the god Zeus and the mortal woman Alcmene. We also know him under the name Hercules, the Roman equivalent of the Greek hero. At any rate, Hercules is rightfully famous for his powerful strength. According to the story, Zeus’ sister-wife Hera wasn’t particularly happy that her husband had fathered yet another child out of wedlock, and she decided to place a poisonous snake in Hercules’ crib during the night. To everybody’s surprise, a giggling baby Hercules throttled the snake with his bare hands. He subsequently goes on to perform a great many adventures, known as the “Twelve Labours.” But growing up with mortals as a teenager, Hercules was not a particularly happy boy. One day he went on an errand for his stepfather and came to a fork in the road. One road was hilly and rough with blue skies ahead, while the other was broad and smooth but covered in mist. While he contemplated which road to take, two beautiful women came towards him on the different roads. Now the lad was truly confused and asked the first woman, “What is your name?” “Some call me Labor,” she answered, “but others know me as Virtue.” He then turned to the other woman and asked her name. “Some call me Pleasure,” she said with a seductive smile, “but I choose to be known as the Joyous and Happy One.” So Hercules had to make a choice, and after some deliberation exclaimed, “Virtue, I will take thee as my guide!” And thus he put his hand into that of Virtue, and they walked down the hilly and rough road towards the blue skies.

George Frideric Handel: The Choice of Hercules, HWV 69 (Heather Harper, soprano; Helen Watts, mezzo-soprano; James Bowman, counter-tenor; Robert Tear, tenor; King’s College Choir, Cambridge; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Philip Ledger, cond.)

Carle van Loo: Perseus and Andromeda

Perseus is one of the greatest heroes of Greek Mythology. He is the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Danae, and he is best known for slaying Medusa. She was a monster described as a winged human female with living venomous snakes in place of hair, and those who gazed upon her face would instantly turn to stone. Well, Perseus had none of it and simply chopped off her head by looking at Medusa’s reflection in a mirror. On his journey home he passed the kingdom of Ethiopia, and came upon the beautiful and helpless maiden Andromeda chained to the rocks waiting to be devoured by a sea monster. Andromeda was the daughter of King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia, and one day Cassiopeia bragged that her daughter was more beautiful than the sea nymphs. Poseidon, the god of the sea became furious at such a boastful statement and unleashed the sea monster Cetus. In the end, it was suggested that the only way to appease Poseidon was to sacrifice Andromeda. When Perseus found her helplessly on the rocky shore he immediately fell in love and quickly killed the monster Cetus. After some tribulations, Perseus married Andromeda, and their children founded the Persian nation and people. Zeus was very pleased, and together with Cassiopeia and Cepheus, they were taken up into the heavens as constellations.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 4 (The Rescuing of Andromeda by Perseus) (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Kehr, cond.)

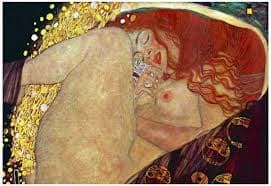

Gustav Klimt: Danaë

By now you can easily tell that all-mighty Zeus did not take his wedding vows entirely serious. In his long amorous career the King of the Gods had transformed himself into all kinds of exotic entities in his pursuit of desirable females, and occasionally males. But in his seduction of Danae he had to be especially inventive. You see, Danae was the daughter of Acrisius, mighty ruler of one of the most important Greek City-States. Because Acrisius had not produced a male heir, he consulted the Oracle of Delphi who bluntly told him that, “he would have no son, but that his grandson would kill him.” King Acrisius was predictably mortified, and he locked his only daughter Danae into a sealed bronze chamber to keep all invaders at bay. But the good king had not reckoned with the cunning of lusty and all-seeing Zeus, who saw the girl and fell in love with her. In the end, Zeus took the form of a shower of golden rain and seduced Danae. We don’t know whether Danae enjoyed the experience, but she did become pregnant and in due time gave birth to a mortal boy by the name of Perseus.

Richard Strauss: Die Liebe der Danae, Op. 83 (Excerpts) (Júlia Várady, soprano; Bamberg Symphony Orchestra; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, cond.)

Frederick Sandys: Medea

Medea was the daughter of King Aeetes of Colchis, and she fell in love with Jason when he sought to claim the Golden Fleece from her father. Of course, the union was arranged by the gods, with Eros freely distributing his love arrows. In order to claim the Golden Fleece, Jason and the Argonauts had to complete a number of tasks. Medea, now deeply in love agrees to help Jason under the condition that he take her with him. The first task was to yoke two fire-breathing oxen and plow a field. Ahead of time, Medea gives Jason an ointment that protects him from the fire of the bulls. For his second task, Jason had to take dragon teeth and sow them in the field he had ploughed. As soon as the teeth touch the soil, an entire army of warriors emerged. But Medea had forewarned Jason, and he threw a rock amidst the army. Since nobody could figure out who had thrown the rock, they started fighting and killing each other. The third and final task was to kill the guardian dragon of the Golden Fleece. No problem, as Medea provides some sleeping herbs and the dragon falls fast asleep. As they sail away with the fleece, the King furiously pursues them. But Medea knows exactly what to do. She kills her brother Absyrtus, dismembers him and throws his body parts into the sea. Their father has to stop and gather all the pieces to give his son a proper burial, allowing Medea and Jason to get away: what a charming story.

Luigi Cherubini: Medea (Maria Callas, soprano; Fedora Barbieri, mezzo-soprano; Giuseppe Modesti, bass-baritone; Gino Penno, tenor; Maria Luisa Nache, soprano; Angela Vercelli, soprano; Maria Amadini, contralto; Enrico Campi, bass; Milan La Scala Chorus; Milan La Scala Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

Titian: Bacchus and Ariadne

The mythical king Theseus was the founder-hero of Athens. Like many other heroes, he had to battle and overcame a number of powerful foes and monsters. And one such monster was kept captive in the great labyrinth constructed by Daedalus, the father of Icarus. I’ve already told you about the Minotaur, who had to be fed seven young Athenian men and seven young Athenian women every nine years, otherwise King Minos would completely destroy the city of Athens. Theseus volunteers to be a sacrifice, and he traveled to the island of Crete where he meets Ariadne, the clever but somewhat naïve daughter of King Minos. When Ariadne first lays eyes on the hero, she immediately falls in love and offers to help him slay the monster. Ariadne gives him a ball of red thread to mark his path in the labyrinth, and Theseus is successful in killing the Minotaur. However, Theseus had absolutely no intention of marrying Ariadne. They do sail for Athens, but during a brief layover on the island of Naxos, he sails away without her while she is sleeping on the beach. Not very heroic, if you ask me. At any rate, Ariadne is sitting utterly distraught on the beach when Bacchus, the god of wine, and his drunken followers spot her. Bacchus is instantly intoxicated, and Ariadne returns his affection. Now there is a happy ending, isn’t it?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Albert Roussel: Bacchus et Ariane, Op. 43, Suite No. 2 (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Stéphane Denève, cond.)