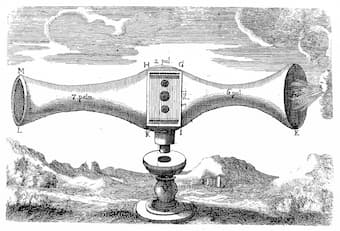

Kircher: Phonuriga nova: Aeolian harp

Sound comes from something vibrating, be it your vocal chords or your guitar strings. What, though, if you want to have sound without using your body? This is where the wind harp comes in.

Set in the outdoors where the winds will set the strings in motion, these wind harps, sometimes called Aeolian harps, from the name for the Greek god of wind, Aeolus, play the air that activates.

The first Aeolian harp we have recorded was written about by the German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in 1650, and this illustration of one appeared in his Phonurgia Nova of 1673. He’s made a complex machine that takes the wind in on the right and drives it across the strings in the middle and the sound emerges on the left.

Eventually, it was found that you didn’t need to have such a complex set up – simply setting some strings in tension against the wind would make them sound.

Aeolian harp in San Francisco

Aeolian harp in Brittany, France

Gurr Aeolian Harp

This Aeolian harp, built by University of South Carolina professor Henry Gurr, was part of an experiment that found out some fundamental properties of wind harps: because the wind, striking the strings, plays all the overtones, they cannot be tuned to be harmonious, because as you go up the overtone series, notes become dissonant with each other, and no matter what tuning you use on the harp, all harps sound the same.

In the overtone series, you start with a fundamental tone (we’ll pick C), the next tone is an octave up (C, the next a fifth (G), the next a perfect fourth (C), the next a major third (E), the next a minor third (G), and so on – Bb, D, E, F, G, Ab, Bb, B-natural, C. Once we get to Bb, we’re going to start to have dissonance against the C. F to B-natural is another dissonance. So, as the overtones accumulate, dissonance increases.

Tornado Memorial in City Park, Eldorado, KS (2008) (Harmony Wind Harps)

A commercial maker of wind harps has his wind harp sculptures as elements in a variety of outdoor spaces including private landscapes and gardens, at hospitals and hospice centers, memorial sites, and so on. This one is set up in Kansas at a Tornado Memorial.

In 1851, we have in the journal of American author Henry David Thoreau:

As I went under the new telegraph wire, I heard it vibrating like a harp high overhead. It was as the sound of a far-off glorious life, a supernal life, which came down to us, and vibrated the lattice-work of this life of ours. … [and later] the wind, which was conveying a message to me from heaven, dropped it on the wire of the telegraph which it vibrated as it passed.

But, this is just sound, not music. It makes something invisible audible.

John Luther Adams in Mexico (photo by Cynthia Adams)

In his new album, Arctic Dreams, American composer John Luther Adams took the sound of wind harps he’d heard on the Arctic tundra and transformed the wind sound into music. By adding vocals and strings and then using electronic delay, he brought the aethereal sound of the wind harps into human range.

The first part sets the scene – an empty landscape with the wind making sound against the wind harp. The low D of the double bass sets the pitch and then he uses the first 7 odd-numbered harmonics above that D.

John Luther Adams: Arctic Dreams – The Place Where You Go to Listen (Synergy Vocals, Robin Lorentz, violin; Ron Lawrence, viola; Michael Finckel, cello; Robert Black, double bass)

When the winds get more active, the music reflects that activity.

John Luther Adams: Arctic Dreams – The Circle of Winds (Synergy Vocals, Robin Lorentz, violin; Ron Lawrence, viola; Michael Finckel, cello; Robert Black, double bass)

The digital delays used in the production have the effect of turning the 4 singers and 4 instrumentalists into a virtual choir and orchestral of 32 voices, with the delay creating a canonic texture. The singers either sing textless vowels or are reciting what he calls ‘Arctic Litanies,’ made up ‘of the names of Arctic places, plants, birds, weather, and seasons, in the languages of the Iñupiat and Gwich’in peoples of Alaska.’

John Luther Adams: Arctic Dreams – One That Stays All Winter (Synergy Vocals, Robin Lorentz, violin; Ron Lawrence, viola; Michael Finckel, cello; Robert Black, double bass)

The music is strikingly effective and evokes much more than the sound of the wind. We can hear the birds, the snow, the infinite horizon in the distance and even the sound of the sky above.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter