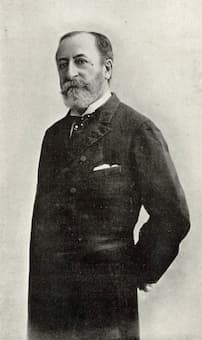

Saint-Saëns

“The Carnival of Animals,” also known as “Le Carnaval des Animaux,” is one of Camille Saint-Saëns’ most famous works. It’s hardly surprising, as bees, bears, birds, cows and all manner of creatures spring to life in the ultimate musical animal kingdom. Surprisingly, that delightful work first premiered on 26 February 1922, 36 years after its creation. You see, in 1886, Saint-Saëns was recovering from a demanding concert tour in a small Austrian village. Feeling inspired, the composer set to work on his famous “Organ Symphony,” but in his leisure time he concocted a plan to write a suite of fourteen movements that humorously depict various animal friends for his students back home.

Title Page of “The Swan”

On 9 February 1886 he wrote to his publishers Durand in Paris that he was composing a work for the coming Shrove Tuesday, and confessing that he knew he should be working on his Third Symphony, but that this work was “such fun.” He had apparently intended to write the work for his students at the École Niedermeyer de Paris, and it was first performed at a private concert given by the cellist Charles Lebouc on 3 March 1886.

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals “The Swan”

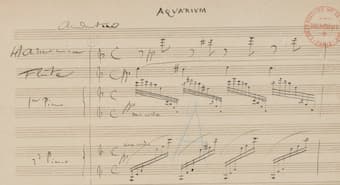

Original manuscript score of “Aquarium”

A critic and eyewitness reports, “Monsieur Lebouc managed to assemble a definitive line-up of eminent performers: Messieurs Saint-Saëns, Diémer, Taffanel, Turban, Maurin, Prioré, de Bailly and Tourcy who, after a very interesting program, took part in the first performance of a very witty fantasy burlesque, composed for this concert by Saint-Saëns and entitled the Carnival of the Animals. This zoological fantasy was received with great enthusiasm.” Only a couple of days later, a second performance was given at Émile Lemoine’s chamber music society La Trompette, followed by another at the home of Pauline Viardot with an audience including Franz Liszt, a friend of the composer, who had expressed a wish to hear the work. There were other performances, typically for the French mid-Lent festival of Mi-Carême. All those performances were semi-private, except for one at the Société des instruments à vent in April 1892, and “often took place with the musicians wearing masks of the heads of the various animals they represented.”

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals – IV. Tortoises – V. The Elephant – VI. Kangaroos (Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; Georges Prêtre, cond.)

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals – VII. Aquarium (Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; Georges Prêtre, cond.)

Score of the “Kangaroos”

Despite its overwhelming success, Saint-Saëns was concerned that his whimsical animal miniatures, full of delightful jokes, might hamper his public image of being a matured and serious composer. He was adamant that the work would not be published in his lifetime, and initially only allowed “The Swan” to be published in 1887. For that occasion, Saint-Saëns fashioned an arrangement for cello and solo piano relying on his original score for two pianos. In fact Saint-Saëns specified in his will that the work should only be published after his death. As such, it was first printed by Durand in Paris in April 1922 and rapturously received. The newspaper “Le Figaro” reported, “We cannot describe the cries of admiring joy let loose by an enthusiastic public. In the immense oeuvre of Camille Saint-Saëns, The Carnival of the Animals is certainly one of his magnificent masterpieces. From the first note to the last it is an uninterrupted outpouring of a spirit of the highest and noblest comedy. In every bar, at every point, there are unexpected and irresistible finds. Themes, whimsical ideas, instrumentation compete with buffoonery, grace and science. … When he likes to joke, the master never forgets that he is the master.”

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals – VIII. People with Long Ears – IX. The Cuckoo in the Depths of the Woods (Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; Georges Prêtre, cond.)

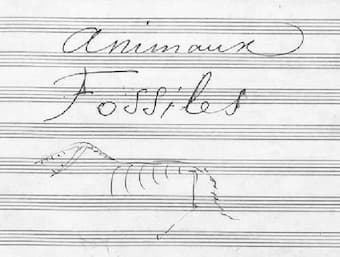

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals – XI. Pianists – XII. Fossils (Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; Georges Prêtre, cond.)

Title page of manuscript of “Fossils”, no. 12 in The Carnival of the Animals

His first version was written for only 11 players, and it included two pianos and a few orchestral instruments, while the final version consists of 14 movements forming a suite, and utilizes two pianos, a xylophone, strings, glass harmonica, clarinet, and flute. In today’s performances, the glockenspiel is frequently substituted for the glass harmonica. Saint-Saëns exploited the sounds of the instruments to perfection, most effectively painting the picture of the animals. The xylophone resembles the clattering of fossil bones, the double bass poses as an elephant, and the violin is clucking like a hen laying an egg. However, The Carnival of Animals not merely provides musical descriptions of the animal kingdom, it also parodies famous composers. We find thematic material originating in Felix Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hector Berlioz’s “Dance of the Sylphs” from his The Damnation of Faust, and even Jacque Offenbach’s famous “Can-Can” from the operetta Orpheus in the Underworld. Saint-Saëns even parodies himself by including an excerpt from his “Danse macabre.” In the immense oeuvre of Camille Saint-Saëns, it represents one of his most creative and delightful journeys into the imagination, and his animal miniatures have rightfully become favorites with audiences worldwide.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals

Carnival of the Animals….my everlasting love!

Carnival of the animals superb rendition the swan, thank you.