Vladimir Horowitz, 1931

From his earliest days, the legendary pianist Vladimir Horowitz wanted to be a composer/performer in the great tradition of Franz Liszt and Sergei Rachmaninoff. In fact, despite his early successes as a pianist, Horowitz always claimed “he wanted to be a foremost composer and undertook a career as a pianist only to help his family, who had lost their possessions in the Russian Revolution.” Horowitz did voice frustration late in life, after having enjoyed a brilliant career as a pianist, that he hadn’t dedicated more of his time to composing. Dreaming of becoming a composer in his teenage years, Horowitz wrote several compositions in the 1920s not only for the piano, but also now lost scores for violin, cello and voice. Original compositions aside, Horowitz also began to fashion marvelous transcriptions “combining artistic fantasy with compelling virtuosity.” Up until the late 1980s, there was no printed music available, that is, until pianist Valery Kuleshov decided to write them down by ear and he performed them in the 1987 Busoni Piano Competition.

Felix Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “Wedding March and Dance” (arr. V. Horowitz) (Valery Kuleshov, piano)

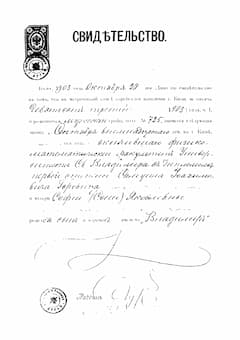

Vladimir Horowitz Birth certificate

After hearing a recording of these performances, Vladimir Horowitz wrote to Kuleshov, “I have listened to your performances, taped at the Busoni Piano Competition 1987: Liszt-Hungarian Rhapsody No. 19 and Mendelssohn –Wedding March. I was not only delighted by your fantastic performances, but I congratulate you on your keen ear and great patience that were required to write out, note by note, the scores of these unpublished transcriptions, by listening to my recordings.” According to his colleagues, Mendelssohn’s Wedding March and Variations was “one of his absolute favorite transcriptions.” It was fashioned in 1946 and based on Mendelssohn’s Wedding March and Liszt’s subsequent paraphrase of the work. Horowitz abbreviated Liszt’s adaptation by removing the “Dance of Elves,” thus restoring the original structure of Mendelssohn’s march. “Horowitz introduced new and spicy harmonies, to which he later became very attached, into this brilliant and sparkling piece.”

Vladimir Horowitz: Etude-fantaise in E-flat Major, Op. 4 “Les Vagues” (Valery Kuleshov, piano)

All surviving original composition crafted by Horowitz originated during his student years in Russia. We have unsubstantiated reports that Horowitz composed furiously between 1911 and 1919, but very few of his efforts seem to have survived. Horowitz did keep some of these manuscripts from his early compositions in his private collection, and when he was asked in an interview toward the end of his life whether he would like to have them published he quickly replied “No…They are too modest.” After his death, his wife Wanda Toscanini ensured that the works remained unpublished. Horowitz dedicated his Étude-fantaisie in E flat major, Op. 4, “Les vagues” to his piano teacher S. Tarnowsky, with whom he studied at the Kiev Conservatory from 1914 to 1919. “Purely romantic and a little bit naïve, this piece shows the musical influence of Rachmaninoff’s Moment Musicaux in C major.

All surviving original composition crafted by Horowitz originated during his student years in Russia. We have unsubstantiated reports that Horowitz composed furiously between 1911 and 1919, but very few of his efforts seem to have survived. Horowitz did keep some of these manuscripts from his early compositions in his private collection, and when he was asked in an interview toward the end of his life whether he would like to have them published he quickly replied “No…They are too modest.” After his death, his wife Wanda Toscanini ensured that the works remained unpublished. Horowitz dedicated his Étude-fantaisie in E flat major, Op. 4, “Les vagues” to his piano teacher S. Tarnowsky, with whom he studied at the Kiev Conservatory from 1914 to 1919. “Purely romantic and a little bit naïve, this piece shows the musical influence of Rachmaninoff’s Moment Musicaux in C major.

Vladimir Horowitz: Waltz in F minor

© Sony Music Photo Archives

Located squarely in the melancholy style of the very early works of Scriabin and Rachmaninoff, the Waltz in F minor by Vladimir Horowitz was composed in the 1920s. An elegant salon dance, it does contain mazurka elements in its rhythmic structure. When Horowitz first visited the United States, he wasted no time and made a piano roll for Welte & Son. That piano roll featured his “Danse Excentrique” originally known as “Moment exotique.” Horowitz had composed this witty piece for the birthday party of his brother when he was only eighteen years of age. Horowitz would subsequently record a slightly different version of this colorful little morceau for RCA in 1930. There has been some question if Horowitz perhaps composed this little gem together with a friend, as the original RCA Victor release is labeled “Demeny/Horowitz: Danse Excentrique.” Demeny, as far as we know, has never been identified. Sergei Rachmaninoff seemed to have had a special fondness for this particular piece, and an anecdote tells that he stopped George Gerswhin playing the piano at a party and commanded to Horowitz, “to sit down and play your Dance.”

Vladimir Horowitz: Danse Excentrique

© Bain Collection

Of all the Horowitz transcriptions, the “Variations on a Theme from Carmen” is the only one to remain in his repertoire throughout his career. He played them from his earliest concerts in the 1920s all the way through to his golden jubilee season in 1978, over fifty years later. The origin of the work can be found in the collaboration between Nathan Milstein and Horowitz in the 1920s. They frequently performed the Carmen Variations for violin and piano as arranged by Sarasate, based on the theme of the gypsy song and dance from the second act of Bizet’s opera. Apparently, Horowitz became bored with playing the simply accompaniment and decided to create his own variations inspired by Moszkowski’s transcription. In 1923, Horowitz wrote his first version of Carmen, “a sparkling mixture of Bizet, Moszkowski, Sarasate, and Horowitz with the virtuosity and impetuosity that only he could produce.” For Horowitz, the “Carmen Variations” has always been a virtuoso showpiece, but as the years progressed, the variations became more sophisticated. In fact, there are five main versions and a couple auxiliary forms of the piece. Horowitz made the last recording of the Carmen Variations in February 1978 at a televised White House concert celebrating the 50th anniversary of his American debut. Horowitz was clearly proud of his achievement, as he slipped in a couple of bars of his Carmen Variations during the 1985 filming “The Last Romantic.”

Vladimir Horowitz: Variations on a Theme from Bizet’s Carmen

Danse Macabre by Camille Saint-Saëns started out as an art song for voice and piano with a text by the poet Henri Cazalis in 1872. Two years later, the composer expanded the work into a tone poem for orchestra, with the vocal line taken by the solo violin. Franz Liszt, a close friend of Saint-Saëns, went to work shortly after the premiere and produced a hauntingly difficult piano transcription. At the beginning of his performing career, Vladimir Horowitz would frequently perform that particular Liszt transcription. However, in 1941 he produced his own, devilishly difficult version. From the twelve strokes at midnight emerges an awful whirl. Skeletons rattle against tombstones and the lyrical melody is set against glittering passagework. “Horowitz uses a wide spectrum of pianistic techniques, creative pedaling, and his habitually huge dynamic contrasts.” Horowitz played this transcription during a single concert season, and when asked why he did not play it more, he answered, “Too much macabre!”

Franz Liszt: Danse macabre (arr. Horowitz)

The pianist Jan Holcman was looking to write down a Horowitz work, and when Horowitz heard about the attempt, he wasn’t pleased at all. In fact, he sent his lawyer to Holcman and offered him exactly 34 Dollars if he never published or showed the manuscript to anyone. If he did, according to this anecdote, Horowitz would use his legal right to sue Holcman. Apparently the pianist did not take Horowitz’s offer or threat seriously, and I still don’t know what piece this anecdote actually refers to. It probably wasn’t the 1947 Horowitz transcription from Mussorgsky’s vocal cycle Sunless. Horowitz did not actually change the music, but reconstructed the piece by combining the vocal and piano parts of the score. He did, however, change the color palette by guiding the melody through different registers and doubling the melody in octaves.

Modest Mussorgsky: “By the Water” (arr. Horowitz) (Valery Kuleshov, piano)

For many years, Vladimir Horowitz was not allowed to leave the stage without performing a number of encores. He generally played his Carmen Variations or his transcription of John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever. Horowitz looked upon the process of transcription as the “musical equivalent of the translation of a text from one language to another.” And in the explosively virtuosic Stars & Stripes, Horowitz “shows himself capable of both recreating and producing any kind of sound on the piano with a glowing conviction.” This particular showpiece was composed to celebrate the end of World War II, and the fact that Horowitz had become a citizen of the United States. From the very beginning, audiences were over the moon and they started calling Horowitz the “one-man band.” The original compositions and transcriptions by Vladimir Horowitz pay homage to the pianist’s technical ease, power, wide color palette, singing tone and astute musicianship. “What made Horowitz great,” according to his former manager Peter Gelb, “was the spontaneity of his performances, which far outshone the meticulously edited recordings… The Horowitz mystique and charisma inevitably turned the hall into an intimate space.” Horowitz was capable of “producing extraordinary differences in interpretation to the same repertoire, yet he suffered through extended periods of self-doubt.” As a showman he was quiet and undemonstrative at the keyboard, and in his compositions and transcriptions we “find a serious, intelligent musician who combined mind and instinct wonderfully well.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Sousa: The Stars and Stripes Forever (arr. Horowitz)

Amazing maestro of pianoforte.He is unsurpassed ..marvellous to hear this today.