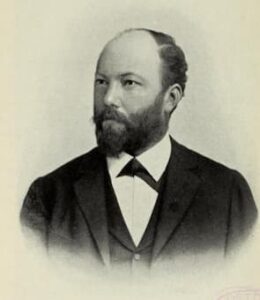

Antonín Dvořák

With his Cello Concerto in B minor, Op.104, Antonín Dvořák created one of the all-time greatest works in the genre. Yet curiously, Dvořák had written in 1865, “The cello is a beautiful instrument, but its place is in the orchestra and in chamber music. As a solo instrument it isn’t much good… it whinges up above, and grumbles down below. I have written a cello concerto, but am sorry to this day that I did so, and I never intend to write another.”

Hanuš Wihan

This curious comment actually refers to a Cello Concerto in A major that Dvořák wrote during the early stages of his career. Inspired by his love for Josefina Cermakova and writing for his close friend Ludevít Peer, who also played in the Provisional Theatre orchestra, the work was left un-orchestrated and merely existed in piano score. It was only at the relentless insistence of his close personal friend, the famed cellist Hanuš Wihan, that Dvořák once again approached a cello concerto almost 30 years later. Dvořák was in his third term as the Director of the National Conservatory in New York when he set to work on 8 November 1894. He informed his friend Alois Gobel, writing, “I’ve just finished the first movement of a concerto for cello! Don’t be surprised; I was surprised myself, and I still wonder why I chose to embark upon something like that.”

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 “Allegro”

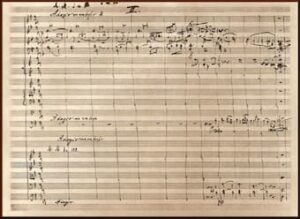

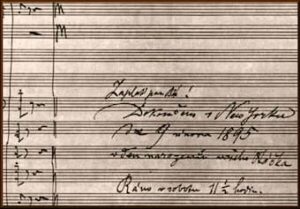

Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor manuscript

It has been suggested that a key impulse which “led to Dvořák’s decision to choose this genre was his experience of the premiere of Cello Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 30, by American composer and cellist Victor Herbert, held in New York on 9 March 1894.” Herbert was Dvořák’s colleague from the National Conservatory, where he taught the cello, and he was also principle cellist with the New York Philharmonic Society. Dvořák attended the premiere and he was much impressed by the instrumentation “especially at one point in the work, in the free movement, where Herbert used three trombones—but so shrewdly that they didn’t stifle the solo cello, and the instrument clearly projected through them.”

Dvořák worked on his concerto for three months and completed the work on 9 February 1895. It is dedicated to his friend Hanuš Wihan, a colleague from the Prague Conservatoire. Composer and performer met at Luzany castle in September 1895 and played through the entire concerto. Wihan proposed several minor changes to the solo part, most of them were accepted by Dvořák. Wihan, however, was still not entirely satisfied and attempted to make various improvements, including the addition of two cadenzas.

Dvořák worked on his concerto for three months and completed the work on 9 February 1895. It is dedicated to his friend Hanuš Wihan, a colleague from the Prague Conservatoire. Composer and performer met at Luzany castle in September 1895 and played through the entire concerto. Wihan proposed several minor changes to the solo part, most of them were accepted by Dvořák. Wihan, however, was still not entirely satisfied and attempted to make various improvements, including the addition of two cadenzas.

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 “Adagio ma non troppo” (Heinrich Schiff, cello; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

Dvořák would have none of it and wrote to his publisher Simrock, “I must insist that my work be published just as I have written it. I give you my work only if you promise me that no one—not even my esteemed friend Wihan—shall make any alteration in it without my knowledge and permission, also that there be no cadenza such as Wihan has made in the last movement. In short, it has to remain the way I have felt it and thought it out… The finale ends gradually in a diminuendo, like a slow exhalation—with reminiscences from the first and second movements—the solo fades away to pp, then there is a crescendo, and the last measures are taken up by the orchestra, ending stormily. That is my idea and I cannot abandon it.”

Dvořák would have none of it and wrote to his publisher Simrock, “I must insist that my work be published just as I have written it. I give you my work only if you promise me that no one—not even my esteemed friend Wihan—shall make any alteration in it without my knowledge and permission, also that there be no cadenza such as Wihan has made in the last movement. In short, it has to remain the way I have felt it and thought it out… The finale ends gradually in a diminuendo, like a slow exhalation—with reminiscences from the first and second movements—the solo fades away to pp, then there is a crescendo, and the last measures are taken up by the orchestra, ending stormily. That is my idea and I cannot abandon it.”

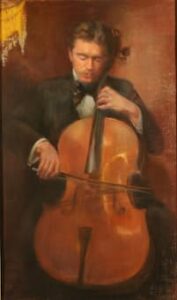

Leo Stern

Although Dvořák had rejected most of Wihan’s suggested changes, Dvořák still very much wanted Wihan to premiere the work publicly and had promised him that role, but it was not to be. The Secretary of the London Philharmonic Society Francesco Berger, wrote Dvořák in November 1895 and invited him to conduct a concert of some of his works in London. Dvořák happily agreed and proposed to conduct the premiere of his Cello Concerto with Wihan as soloist. Berger had his sights set on 19 March 1896, but that date was not convenient for Wihan, as it clashed with concert dates for the Bohemian Quartet, to which Wihan was already contracted.

This is where things get interesting, because the Philharmonic Society insisted on the date and hired the English cellist Leo Stern without consulting Dvořák. The composer was not amused, and at first refused to come to the concert. This turned out to be a major embarrassment for Berger, as the concert had already been advertised. In the end, Wihan released Dvořák from his promise, and the work premiered on 19 March 1896 in London, with Leo Stern as the soloist. A critic wrote, “In wealth and beauty of thematic material, as well as in the unusual interest of the development of the first movement, the new concerto yields to none of the composer’s recent works; all three movements are richly melodious, the just balance is maintained between the orchestra and the solo instruments, and the passages written for display are admirably devised… Mr. Leo Stern played the solo part with good taste, musical expression, and faultless technical skill, and the work was received with much enthusiasm.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 “Finale-Allegro moderato”