“Work like a slave; command like a king; create like a god”

Constantin Brâncuși

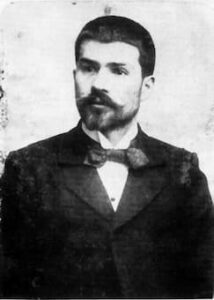

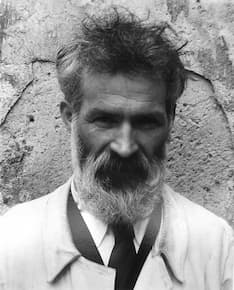

The majority of photographs taken of French-Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957) show a kind of Grizzly Adams, a man with unkempt hair, long beard, a deeply lined face and clothes that are reminiscent of a vagrant. He almost looks like a caricature, but underneath that rugged exterior we find the father of Modernist abstract sculpture. In fact, “he pioneered the technical and aesthetic concerns that have shaped the way we understand abstract sculpture today.

You see, in 1927, a customs official famously refused to recognize “Bird in Space” as a work of art, “and instead tried to impose the 40 percent customs duty typically applied to things like kitchen utensils.” Sculptures, according to U.S. tax laws at the time were “defined as reproductions by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form.”

You see, in 1927, a customs official famously refused to recognize “Bird in Space” as a work of art, “and instead tried to impose the 40 percent customs duty typically applied to things like kitchen utensils.” Sculptures, according to U.S. tax laws at the time were “defined as reproductions by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form.”

Brâncuși and Rochet & Erik Satie playing golf

Brâncuși went on to launch a formal legal complaint, which eventually led to a completely new definition of art. The ruling judge wrote, “There has been developing a so-called new school of art, whose exponents attempt to portray abstract ideas rather than intimate natural objects. Whether or not we are in sympathy with these newer ideas…we think the facts of their existence and their influence upon the art worlds as recognized by the courts must be considered.”

Erik Satie: Gymnopédie No.1

Brâncuși: Bird in Space

In essence, the judge ruled, “whether or not a viewer can get behind Brâncuși’s version of reality or representation, the artist opens up a dialogue that multiple subjective viewpoints exist and are worth our consideration.” To be sure, Brâncuși radically simplified figurative forms, composing works in bronze, marble, stone, and wood. “His elegant geometric volumes reexamine representation, often employing ovoid and elliptical shapes to evoke movement, repose, or spiritual reflection.” As he once declared, “what my work is aiming at is, above all, realism. I pursue the inner, hidden reality, the very essence of objects in their own intrinsic fundamental nature; this is my only deep preoccupation.”

Brâncuși: Fish

Brâncuși was born to a peasant family in the Romanian countryside, about 50 miles from the modern Serbian border. An area richly steeped in folk art, he was herding sheep at the age of seven and he “grew up distinctly outside of the traditional Western European narrative.” He was an outsider from the very beginning, and he would eventually break with the academic tradition to radically shape non-representational modernism. He ran away from home multiple times and made his way to the city of Craiova, working odd jobs but eventually taking woodworking classes.

George Enescu: Romanian Rhapsody No. 2, Op. 11

Brâncuși: The Kiss

According to an unsubstantiated anecdote, Brâncuși created a violin by hand with materials he found around his workplace at the age of 18. Apparently, an industrial patron was much impressed and funded Brâncuși’s education at the National School of Fine Arts in Bucharest. He graduated with honors and made his way—there are some reports that he walked almost 2,000 kilometers—to reach Paris in 1904. He quickly became immersed in avant-garde circles in Paris, maintained friendships with Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Erik Satie, and Marcel Duchamp.

Significantly, he became an assistant in the studio of famed Auguste Rodin. Yet within a short period of time, Brâncuși left to establish his own studio. In fact, “Brâncuși took the search for the spirit of his subjects in a completely different direction, rejecting realistic form altogether in search of an abstracted form that could communicate what he called the inner hidden reality; to reveal essence rather than merely copy outward appearance.”

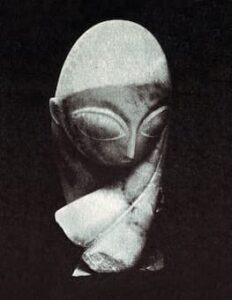

His decision to create non-representational sculpture was a deliberate artistic choice. Brâncuși never made casts, but shaped every sculpture individually. A model sitting from him in 1912 recalled, “Each time he began and finished a new bust in clay it was beautiful and had a wonderful likeliness, and each time he only laughed and threw it back into the boxful of clay. The finished sculpture, instead, was a curious sort of portrait: a large ovoid with disembodied arms and otherworldly, resting eyelids, just scarcely echoing the basic features of a woman’s head.”

Béla Bartók: Allegro barbaro (György Sándor, piano)

Brâncuși: Portrait of Mlle. Pogany

Brâncuși’s works quickly became popular in France and the United States, and he was exhibited at the first exhibition in the U.S. of modern art, the Armory Show in 1913. “At the left hand, a critic wrote, is a much-discussed portrait bust of Mlle. Pogany, a dancer. This freak sculpture resembles nothing so much as an egg and has excited much derision and laughter.” The phallic appearance of the large, gleaming bronze piece named Princess X caused a scandal in the early 1920s.

Brâncuși was commissioned to build a meditation temple for the Maharajah of Indore in 1933, and he finished the World War I monument in Târgu-Jiu in 1938. As his fame grew, Brâncuși withdrew and in the remaining 19 years of his life he created fewer than 15 pieces, mostly reworking earlier themes. In 1955, Life magazine reported, “Wearing white pajamas and a yellow gnome-like cap, Brâncuși today hobbles about his studio tenderly caring for and communing with the silent host of fish, birds, heads, and endless columns which he created.”

Brâncuși: Princess X

Brâncuși died on 16 March in Paris, and he never saw the beauty of sculpture as lying in the recreation of the physical form, but rather in the revealing of something previously invisible. As he famously wrote, “There are idiots who define my work as abstract; yet what they call abstract is what is most realistic. What is real is not the appearance, but the idea, the essence of things.” And we do know that music represented Brâncuși’s secret passion. “The music of Wagner sounded barbarian, that of Beethoven too dramatic, whereas Mozart he deemed gentle and sweet,” he explained. And he compared J. S. Bach with a “lion stepping majestically in the desert.” And György Ligeti named his etude “Infinite Column” after the Târgu-Jiu sculpture of the same name.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

György Ligeti: Etudes, Book 2, No. 14 “Coloana infinita” (Idil Biret, piano)