Antonín Dvořák

The Prague-based, Czech language music magazine Dalibor reports on 2 May. “Our nation has received a terrible, terrible blow, Antonín Dvořák is no more. Yesterday, at half past twelve in the afternoon, he died from sudden heart failure, having been confined to his bed for a whole month. Irreplaceable is the loss we now suffer with so premature a demise and, in these first few moments of anguish, we cannot even imagine its impact. With his passing, Czech music has lost everything, which helped it conquer its position abroad over the last thirty years, and the gold throne from which the maestro dominated a world enthralled by the magic of his genius, will remain abandoned and vacant.” In March 1904, Dvořák had attended the premiere of his very last work, the opera Armida. However, things had not gone smoothly as a careless staging of the opera was compounded by the composer’s health problems. Experiencing acute kidney pain, Dvořák was forced to leave the theatre during the performance.

Antonín Dvořák: Armida, Op. 115 (Joanna Borowska, soprano; Pavel Daniluk, bass; George Fortune, vocals; Vratislav Kříž, baritone; Miroslav Podskalský, bass; Wiesław Ochman, tenor; Milan Bürger, bass; Richard Sporka, vocals; Zdeněk Harvánek, vocals; Jan Markvart, vocals; Vladimír Nacházel, vocals; Roman Janál, bass; Monika Brychtová, vocals; Prague Chamber Chorus; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Gerd Albrecht, cond.)

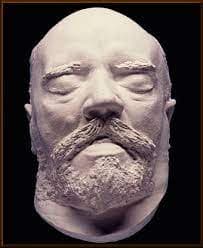

Dvořák’s death mask

Dvořák’s kidney problems were quickly compounded when he experienced a chill followed by influenza. His doctor prescribed plenty of bed rest, and on the morning of 1 May the composer seemed to be feeling better as he wanted to join his family for Sunday lunch. “After having some soup, however, he felt ill and soon lost consciousness. The doctor was summoned immediately, but could only confirm that the composer had died; a stroke was cited as the official cause of death.” It has since been suggested that the cause of death was probably pulmonary embolism, which Dvořák would have suffered after spending nearly five weeks in bed. Dvořák’s last words were hardly profound, as he said, “I feel a bit dizzy, I think I’ll go and lie down.” News of his death soon reached his closest friends and relatives, thus, by the afternoon, various people had arrived at the flat to pay their respects, including the sculptor Josef Maratka, who took the composer’s death mask and created a cast of his right hand.

Antonín Dvořák: “Bouquet of Czech Folksongs,” Op. 41 (The Prague Singers; Stanislav Mistr, cond.)

Dvořák’s funeral procession

A meeting convened at the Old Town Hall in Prague on 3 May to organize Dvořák’s funeral. Representatives from the Prague City Council where joined by the Czech Academy of Sciences and Arts, the Philosophical Faculty of Charles University, the Prague Conservatoire, the Artist association “Umelecka beseda,” and the composer’s family. At the heart of Dvořák’s funeral was a procession that meandered through the streets of the city of Prague. Initially, Dvořák’s coffin was brought from his flat to the church of the Holy Saviour in the morning of 5 May, where the body lay in wake for several hours.

Dvořák’s funeral

According to contemporary reports, thousands of people paid their last respects, and two funeral laments were sung by the Prague-based choral society. The funeral procession got underway at three in the afternoon, headed by members of the “Sokol” movement and followed by students in historical costume. A second group featured various musical delegations and members of a variety of trades and businesses. Then followed representatives of organizations and music companies, “girls dressed in white robes, and a group of priests. Behind them rode a gold funeral carriage bearing the coffin drawn by six horses, with Dvorak’s family behind it.”

Antonín Dvořák: A Hero’s Song (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Dvořák’s tomb

The procession initially headed for the National Theatre, and the theatre orchestra and choir performed excerpts from Dvořák Requiem. The route continued to the church of St Ignatius and down to the Czech Technical University. Finally, the procession arrived at Vysehrad cemetery, and the coffin was placed on the altar of the Slavin tomb. The director of the Prague Conservatoire Karel Knittl gave a memorial speech, and a choir sang a funeral lament. “The coffin was then placed in a temporary grave (Dvořák’s remains were transferred to the family tomb two years later, on the anniversary of the composer’s death).” The grandeur of Dvořák’s funeral might well be compared to official state funerals, “with thousands of people who witnessed the occasion provide proof of the universal recognition of the significance of Dvořák’s work for Czech and world culture.” As a symbol of Czech unity, participation in the funeral process was seen as a manifesto and patriotic gesture in support of Czech independence. Dvořák’s funeral Mass was held on 7 May and featured a performance of Mozart’s Requiem.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: The Devil and Kate, “Act 1”