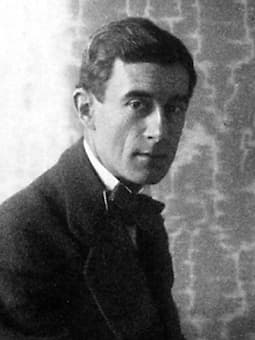

Maurice Ravel at the piano, 1912

On 21 September 1927, Anton Webern penned an extended letter to Maurice Ravel. “Although we have never met, I write on behalf of my mentor Arnold Schoenberg to express his thanks for all your efforts to facilitate his upcoming appearance in Paris. Without your advocacy of his work to the Société Musicale Indépendante, it is doubtful that Schoenberg’s works would have been heard in France for quite some time.”

Webern continued, “I confess immediately, however, that I also write on my own behalf. Like Schoenberg, I too desire most ardently to align myself with the Société Musicale Indépendante, and I write in humility to request the honor of a premiere with your society. I have dreamt of partaking in a musical program under SMI leadership ever since I attended two SMI concerts in December 1915 during my first trip to Paris… Thanks to your vision, the Société Musicale Indépendante exists to combat musical censorship, permitting voices and styles to be heard that would otherwise be stifled by Vincent d’Indy’s exclusive and demanding aesthetic requirements.” Ravel, in fact, had been a founding member of the Société Musicale Indépendante in 1910, with the aim of supporting contemporary musical creations, freeing it from restrictions linked to the forms, genres and styles of programmed works.

Webern continued, “I confess immediately, however, that I also write on my own behalf. Like Schoenberg, I too desire most ardently to align myself with the Société Musicale Indépendante, and I write in humility to request the honor of a premiere with your society. I have dreamt of partaking in a musical program under SMI leadership ever since I attended two SMI concerts in December 1915 during my first trip to Paris… Thanks to your vision, the Société Musicale Indépendante exists to combat musical censorship, permitting voices and styles to be heard that would otherwise be stifled by Vincent d’Indy’s exclusive and demanding aesthetic requirements.” Ravel, in fact, had been a founding member of the Société Musicale Indépendante in 1910, with the aim of supporting contemporary musical creations, freeing it from restrictions linked to the forms, genres and styles of programmed works.

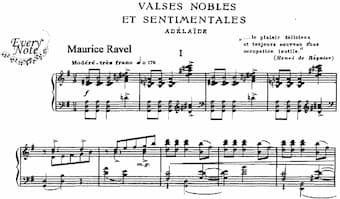

Maurice Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales (Original Version)

Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales

On 8 May 1911, the Society held an anonymous concert with the audience tasked to guess the composer of each piece. The idea of presenting works anonymously had been hatched by Ravel, as he writes, “On the initial performance of a new musical composition, the first impression of the public is generally one of reaction to the more superficial elements of its music, that is to say, to its external manifestations rather than to its inner content. The listener is impressed by some unimportant peculiarity in the medium of expression, and yet the idiom of expression, even if considered in its completeness, is only the means and not the end in itself, and often it is not until years after, when the means of expression have finally surrendered all their secrets, that the real inner emotion of the music becomes apparent to the listener.” The French composer, pianist, and conductor Louis Aubert, a fellow student at the Conservatoire and lifelong friend of Ravel sat down at the piano and began to play. Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales was the fourth work on the program, and when “the voting results were made public, it became clear that the sophisticated, avant-garde audience was unable to distinguish Debussy from Léo Sachs, or Ravel from Lucien Wurmser. Although a slight majority correctly identified Ravel as the author, many credited the work to Erik Satie or Zoltán Kodály.”

Maurice Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales (arr. J. Heifetz for violin and piano)

Adelaide, 1912

As Ravel wrote in a short autobiographical sketch, “The title Valses nobles et sentimentales sufficiently indicates my intention of composing a series of waltzes in imitation of Schubert. Here we have a markedly clearer kind of writing, which crystallizes the harmony and sharpens the profile of the music.” When this suite of waltzes, consisting of seven distinct waltzes followed by an eighth in the form of an epilogue was published in 1911 it carried a quotation by Henri de Régnier: “…le plaisir délicieux et toujours nouveau d’une occupation inutile” (the delicious and forever-new pleasure of a useless occupation). A scholar writes, “The highly polished surface that is so easy to listen to reveals a complex and highly organized musical structure underneath. It was always Ravel’s intention to be complex, but not complicated, and to value technical perfection balanced by charm and sincerity.”

In 1912, Ravel produced an orchestral transcription of his Valses nobles et sentimentales for a performance as a ballet. Ravel actually wrote his own scenario, which takes place in Paris around 1820. The scene takes place at the home of the courtesan Adelaide, with a window looking out onto a garden. It tells the story of Adelaide and her rival suitors, Lorédan and the Duke. The various emotions of love, hope, and rejection are symbolized by the flowers, which the dancers exchange throughout the ballet. Titled “Adélaïde, ou le langage des fleurs” the ballet was first performed on 22 April 1912.

In 1912, Ravel produced an orchestral transcription of his Valses nobles et sentimentales for a performance as a ballet. Ravel actually wrote his own scenario, which takes place in Paris around 1820. The scene takes place at the home of the courtesan Adelaide, with a window looking out onto a garden. It tells the story of Adelaide and her rival suitors, Lorédan and the Duke. The various emotions of love, hope, and rejection are symbolized by the flowers, which the dancers exchange throughout the ballet. Titled “Adélaïde, ou le langage des fleurs” the ballet was first performed on 22 April 1912.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales (Version for Orchestra)