Berndardo Strozzi: Claudio Monteverdi (ca. 1630)

Losing a parent, spouse, child, sibling or a very dear friend is one of life’s most difficult experiences. Although we all are aware of the transitory nature of life, we can never be fully prepared for death. And in times of COVID-19, mourning the death of a loved one is even made more difficult. Unable to conduct a traditional funeral or service, and being potentially quarantined alone at home, can make the process of grieving even more trying. There is no right or wrong way to grieve, and composers throughout the ages have found solace in the process of composition.

Monteverdi: Scherzi musicali

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) met and subsequently wed the professional singer Claudia Cattaneo in 1599. Claudia bore three children, but by 1607 she had fallen gravely ill. Despite the best medical treatment at hand, she passed away on 10 September of that year. Monteverdi was devastated and lamented “the loss of a woman so rare and gifted with such virtue.” Left alone with two underage children, Monteverdi became depressed and prone to illness. However, in his Scherzi musicali (Musical Jokes) of 1607 he therapeutically elected to musically focus on some bright moments from the past, including a beautiful bridesmaid.

Claudio Monteverdi: Scherzi musicali, SV 230-245: Damigella, SV 235 (arr. for vocal ensemble and chamber ensemble) (Philippe Jaroussky, counter-tenor; Núria Rial, soprano; Jan van Elsacker, tenor; Cyril Auvity, tenor; Nicolas Achten, baritone; João Fernandes, bass; L’Arpeggiata; Christina Pluhar, cond.)

Anselm Feuerbach: Battle of the Amazons

The painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880) created a number of stunning landscapes, yet his principal interest lay in the idealistic depiction of classical scenes. Spending a good portion of his life in Italy, he was greatly influenced by the painters of the Italian Renaissance. Johannes Brahms was introduced to Feuerbach in 1865, and his enthusiasm for his paintings is well documented. Feuerbach had been offered to join the Viennese Academy, and hoped to impress his audience with two monumental paintings, “Plato’s Symposium,” and “The Battle of the Amazons.”

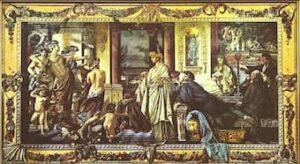

Anselm Feuerbach: Plato´s Symposium

Brahms cautioned him to not set his expectations too high, and Feuerbach was somewhat offended. When Feuerbach’s paintings were exhibited in Vienna in 1874, they met with the hostile reception predicted by Brahms. Brahms continued to hold Feuerbach’s painting in high regard, but by 1876 the relationship had definitely cooled. Brahms writes, “I have been ready to forgive much to Feuerbach, whose art, which has been misunderstood for so long and so widely, I esteem most highly. But I find his utter indifference toward all and sundry quite intolerable. I see him almost daily, and regretfully, content myself with greeting him.” The news of Feuerbach’s death four years later, however, profoundly affected Brahms, and led him to set Schiller’s poem Nänie in memory of his former friend. Not unlike his Requiem, written a decade early, Nänie sounds a similar approach of consolation for those who mourn death.

Johannes Brahms: Nanie, Op. 82 (San Francisco Symphony Chorus; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Herbert Blomstedt, cond.)

Olga Janáčková, 1892

In 1900, Olga Janáčková had fallen in love with the son of her mother’s former piano teacher. When her father Leoš Janáček heard of the impending romance, he strictly forbad her to ever see the young man again. Olga was only 15, and eventually she broke off the relationship, with the young man threatening to shoot her during his next visit. The Janáček family was alarmed, and quickly dispatched their daughter to St. Petersburg. At the end of April Olga fell ill with typhoid fever, and although she made a partial recovery, she relapsed in June. The Janáčeks immediately left for St. Petersburg and her mother Zdenka remained with Olga.

Olga Janáčková, 1900

Leoš turned to his duties in Brno, but wrote to Olga several times a day. After several weeks Olga was finally allowed to return to Moravia, but her condition deteriorated alarmingly during the journey home. Her heart had become weaker, her liver and kidneys were both affected, and she had another attack of rheumatoid arthritis. She continued to suffer and by February 1901, Olga had become delirious. She died on 26 February, with the entire household kneeling by her bedside. Deeply affected by her death, the family friend Marfa Nikolajeva Veverica wrote verses, which the composer immediately set to music. It is a dialogue between tenor and the mixed chorus meditating on death, and evoking the “beautiful face of the girl who lies asleep for all eternity.”

Leoš Janáček: Elegy on the Death of my Daughter Olga (Thomas Walker, tenor; Cappella Amsterdam; Daniel Reuss, cond.)

The Bach Family © Oxford Bach Soloists

It has been said that Johann Sebastian Bach had two constant companions throughout his life: Music and Death! Joy and sorrow were everyday occurrences in the household of the Bach family. All too frequently, his family life was overshadowed by tragedy as only ten of his 20 children survived into adulthood. The stark facts of his immediate experiences of death, shocking as they are when compared with modern western expectations, would not have been exceptional in late seventeenth-century Germany. As an orthodox Lutheran, Bach would have accepted that faith alone prepared the way for salvation. He might actually been aware of Martin Moller’s Manual on Preparing for Death, which talks of the blessed death, “To die blessedly means to end one’s life in the correct and true faith, to commend one’s soul to the Lord Jesus Christ, and with a heartfelt desire for external blessedness, to go to sleep gently and pass on over.” Music, for Bach, was a fundamental tool of religion and essential to this religious life. And undoubtedly, his prevailing and comforting attitudes towards death and mourning inevitably surface in his compositions.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

J.S. Bach: Klagt, Kinder, klagt es aller Welt, BWV 244a (Sabine Devieilhe, soprano; Damien Guillon, alto; Thomas Hobbs, tenor; Christian Immler, bass; Pygmalion; Raphaël Pichon, cond.)