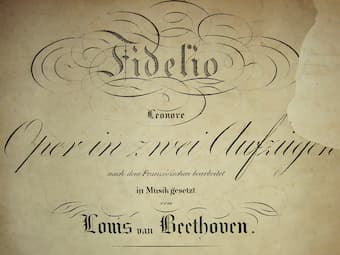

Beethoven: Fidelio

As you can tell from the title, Beethoven’s only opera Fidelio was a long time in the making. In fact, the process of composition and revision took nearly 10 years, from the first failure in 1805 to the premiere of the final version on 23 May 1814. Originally it was titled “Leonore, oder Der Triumph der ehelichen Liebe” (Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love), and based on an actual incident from the French Revolution. A woman dressed as a man was hired as a prison warden and managed to free her incarcerated husband. The origin of Fidelio actually dates from 1803, when the librettist and impresario Emanuel Schikaneder—the producer of Mozart’s “Magic Flute,” worked out a contract with Beethoven to write an opera. Schikaneder first provided him with a libretto titled “Vestas Feuer,” but after composing music for it for about a month, Beethoven abandoned the project when the libretto for “Fidelio” became available. Beethoven quickly reused some of the music, and the first version, with the libretto adapted by Joseph Sonnleithner, premiered on 20 November 1805 at the Theater an der Wien.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Fidelio, Leonore’s aria “Abscheulicher, komm Hoffnung”

Beethoven in 1814

That particular performance wasn’t a resounding success, and it was suggested that Beethoven shorten the opera into two acts and compose a new overture. Talking about overtures, Beethoven really had a difficult time producing an appropriate overture and ultimately produced four versions. We believe that Beethoven used his “Leonora No. 2” during the 1805 performance. In 1806, Beethoven shortened his opera and composed an entirely new overture, known as “Leonora No. 3.” A further reworking of the opera anticipated the name “Fidelio,” and Beethoven’s third new overture is usually referred to as “Leonora No. 1.” Finally the opera “Fidelio,” together with yet another newly composed overture bearing the same name, emerged in 1814. Beethoven always thought of his overtures as functioning within a ceremonial or dramatic frame. And even though he had three leftover Leonora Overtures, he never thought them suitable as independent concert pieces. Nevertheless, it was the fully developed symphonic character of “Leonora No. 3,” alongside the overtures to Collin’s “Coriolan” and Goethe’s “Egmont,” that musically and aesthetically foreshadowed the emergence of the stand-alone Symphonic poem.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 2, Op. 72a (Cleveland Orchestra; George Szell, cond.)

Theater an der Wien

Beethoven revised his opera yet again in 1814, with additions to the libretto fashioned by Georg Friedrich Treitschke. The opening scene actually has a backstory. When the Spanish nobleman Florestan exposes crimes committed by the rival nobleman Pizarro, he is secretly imprisoned. Pizarro also spreads false rumors that Florestan has died, but his wife Leonore is unconvinced. The prison warden Rocco has a daughter, Marzelline, and an assistant Jaquino, who is in love with Marzelline. Leonore, meanwhile, gains employment working for Rocco. As the boy Fidelio, she earns the favor of her employer, Rocco, and also the affections of his daughter Marzelline, much to Jaquino’s chagrin. Pizarro is worried about an inspection by the king’s minister, Don Fernando who suspects the sinister governor of abusing his power. He then orders Rocco to kill Florestan, but Rocco refuses. Leonore convinces Rocco to let her accompany him to the dungeon, and he agrees. When Pizarro goes down to the cell to kill Florestan, Leonore reveals herself, steps in and threatens the tyrant. Meanwhile the good minister Fernando arrives, saves Florestan, chastises Pizzaro and frees the prisoners who, in a splendid finale scene, sing a joyful hymn with the people.

Final Chorus from Fidelio

Fidelio’s playbill for the premiere

Finally, the opera was staged under the title “Fidelio,” and at the premier of this final version at the Kärntnertortheater, a young Franz Schubert was in the audience. Interestingly, Johann Michael Vogl, who later became known for his collaborations with Schubert, took the role of Pizarro on that day. This version of the opera was a great success, and Fidelio has been part of the operatic repertory ever since.

Kärntnertortheater

Beethoven found the difficulties of composing and producing an opera so unpleasant that he never again attempted to compose another. As he wrote in a letter to Treitschke, “I assure you, dear Treitschke, that this opera will win me a martyr’s crown. You have by your co-operation saved what is best from the shipwreck. For all this I shall be eternally grateful to you.” The subjects of liberty, faithfulness, idealism and justice strongly resonated with European audiences after the end of World War II and the fall of Nazism. The conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler said in 1948, “The conjugal love of Leonore appears, to the modern individual armed with realism and psychology, irremediably abstract and theoretical…. Now that political events in Germany have restored to the concepts of human dignity and liberty their original significance, this is the opera, which, thanks to the music of Beethoven, gives us comfort and courage….”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Beethoven: Fidelio, Fidelio’s aria “Gott! Welch Dunkel hier”