How the artistic camaraderie between Braque and Picasso inspired classical composers

Georges Braque

Born 140 years ago in Argenteuil, Val-d’Oise, Georges Braque (1882-1963) played a decisive role in the revolutionary art movement of Cubism. Guided from a young age toward creative painting techniques, he initially made his most notable contributions in his alliance with Fauvism. After meeting Pablo Picasso, he developed a Cubist style. “While their paintings shared many similarities in palette, style and subject matter, Braque stated that unlike Picasso, his work was devoid of iconological commentary, and was concerned purely with pictorial space and composition.”

Braque: Femme a la Guitare

(Woman with a Guitar)

Throughout his life, Braque focused on still life and means of viewing objects from various perspectives through color, line, and texture. Always aiming for balance and harmony in his composition, Braque and Picasso invented a pasted paper collage technique in 1912. Braque expanded on this technique by incorporating advertisements into his canvases, “essentially foreshadowing modern art movements concerned with critiquing media.” Achieving great levels of dimension in his painting by blending pigments with sand and copying wood grain and marble, many depictions “are so abstract that they border on becoming patterns that express an essence of the objects viewed rather than direct representations.”

Francis Poulenc: Le travail du peintre – No. 3 “Georges Braque” (Matthias Veit, baritone/piano)

Braque: Maisons et arbre (Houses at l’Estaque)

Braque grew up in Le Havre and initially trained to become a decorative painter like his father and grandfather. In addition, he studied artistic painting in evening classes at the École Supérieure des Arts in Le Havre and was awarded a certificate in 1902. In 1899, at age seventeen, Braque moved from Argenteuil into Paris, accompanied by friends Othon Friesz and Raoul Dufy. He met Marie Laurencin and Francis Picabia at the Académie Humbert and his earliest paintings adopted a Fauvist style. Together with Henri Matisse and André Derain, Braque used brilliant colors to represent emotional response, and his paintings were successfully exhibited at the Salon des Independants in 1906. Braque met Pablo Picasso in 1907, and the two artists forged an intimate friendship and artistic camaraderie. His close association with Picasso is reflected in his new interest in geometry and simultaneous perspective. “We would get together every single day,” Braque said, “to discuss and assay the ideas that were forming, as well as to compare our respective works.” While Gauguin, African masks and Iberian sculpture influenced Picasso, Braque looked to develop Cézanne’s ideas of multiple perspectives. “A comparison of the works of Picasso and Braque during 1908 reveals that the effect of his encounter with Picasso was more to accelerate and intensify Braque’s exploration of Cézanne’s ideas, rather than to divert his thinking in any essential way.”

Erik Satie: Le piège de Méduse “7 Monkey Dances” (Dario Muller, piano)

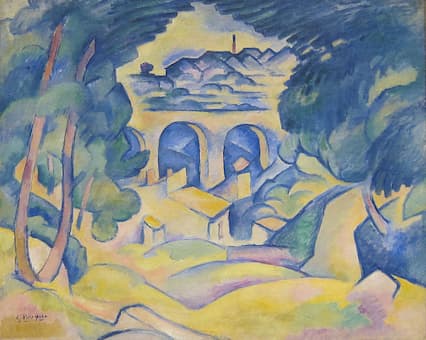

Braque: Le Viaduc à L’Estaque, (The Viaduct at L’Estaque)

An art critic explained “Picasso celebrated animation, while Braque celebrates contemplation.” In the event, the invention of Cubism was a joint effort between Picasso and Braque, the style’s main innovators. Braque and Picasso worked in tandem until Braque returned from war in 1914. While Picasso began to paint figuratively in a style known as “Interwar Classicism,” Braque continued on his own. However, he continued to remain influenced by Picasso’s work, especially in regards to papier collés, a collage technique pioneered by both artists using only pasted paper. Braque’s collages featured geometric shapes interrupted by musical instruments, grapes, or furniture. “These were so three-dimensional that they are considered important in the development of Cubist sculpture.” Braque resumed painting in late 1916, and he moderated the harsh abstraction of cubism believing “that an artist experienced beauty in terms of volume, line, mass, and through that beauty he interprets his subjective impression.”

Igor Stravinsky: Piano Rag

Braque: La Mandore (Mandora)

Braque was most interested in showing how objects look when viewed over time in different temporal spaces and pictorial planes. As a result of his dedication to depicting space in various ways, he naturally gravitated towards designing sets and costumes for theater and ballet performances. As such, he collaborated with Sergei Diaghilev and became a close friend of Erik Satie. Both originally hailed from the Normandy region, and they shared a 16-year friendship that involved weekly lunches. Braque was a great admirer of music who played several instruments including the accordion, flute, and violin. Unsurprisingly he frequently referenced music in his paintings of still life, and in 1921 they collaborated on a printed edition of “Le piège de Méduse,” a short play with music by Satie for which Braque contributed 3 color woodcuts. By 1929, Braque had returned to landscape painting and he soon began to portray Greek heroes and deities, with “the subjects stripped of their symbolism and viewed through a purely formal lens.” Following World War II, Braque painted lighter subjects, and his final series of eight canvases made from 1948-1955 are each titled “Atelier,” or “Studio.” These images “represented the artist’s inner thoughts on each object rather than clues to the outside world.” As Braque once said, “In art there is only one thing that counts: the bit that cannot be explained.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Auric/Demets/Durey/Honegger/Milhaud/Poulenc/Tailleferre: L’Album des Six (Yuji Takahashi, piano)