John Dowland © thefamouspeople.com

The English composer John Dowland (1563-1626) wanted to be lutenist to the English court. Unfortunately, the difficulties in England between Protestants (the court) and Catholics, made Dowland’s desire difficult to achieve, as he had converted to Catholicism while traveling in Europe. Accordingly, he set out to seduce the court by his music. His First Booke of Songs or Ayres (1597) secured him an appointment in Denmark in the service of Christian IV. There, he was one of the most highly paid of the court servants. Christian IV was the brother to Queen Anne, wife of the newly crowned James I of England.

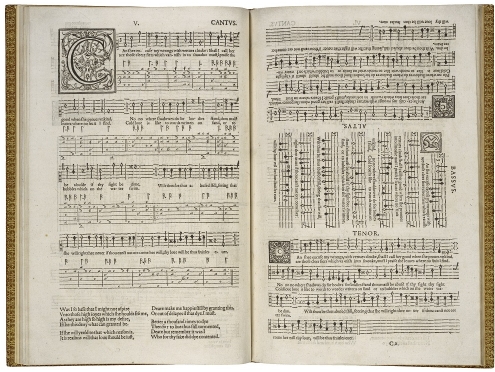

One of the innovations of The First Booke was that it was not printed in partbooks, with each player’s part in a separate book. This music was printed in a single book intended to be laid flat on a table, a singer on each side. The Cantus part, with the lute tablature, is on the left-hand side, the Altus part is printed up-side down, the Bassus part, in the middle, is rotated, and the Tenor part is printed right-side up at the bottom of the right-hand page. This innovation set a new standard for lute-songs. Any number of singers could sing – just the cantus or cantus and any other voices.

Dowland: The First Booke of Songs or Ayres (1597)

One of the most famous of his lute songs comes from his second book, published in 1600. The second song in the book is the lament Flow My Tears. In the poem, the poet gives himself over to the greatest depression: all is lost, he is in utter shame, he dwells in darkness, and even those who are in Hell have to be happier than he is, having lost everything.

Most modern recordings express this as an exquisite solo, building to the last lines of the poem.

An early recording by the counter tenor Alfred Deller, made in 1953, slows the tempo and makes it very dramatic. At the time of this recording, Alfred Deller (1912-1979) was one of the main figures who brought back the male high countertenor voice into use. It had survived in England in the many all-male church choirs, but in secular music, it was gone. By bringing it back, a new avenue into Renaissance and Baroque music opened, and there was a renaissance again of music from the 16th and 17th centuries. Deller’s performance is slow, deliberate, and continues to slow through the verses, bringing the audience into his picture of despair.

John Dowland: Book of Songs, Book 2 – Flow, my tears, fall from your springs (Alfred Deller, countertenor; Robert Spencer, lute)

When we contrast this with a recording made in 1987, we can hear how the performance has changed. In this limpid recording by the tenor Rogers Covey-Crump, he lets the music sound for itself. The poem is sung at reading speed, and it is only on the last verse (Harke you shadows…) that he slows and then lands on the word ‘hell’ to emphasis the contrast with the ‘happie, happie’ that began that line.

John Dowland: Flow my tears (Lachrime) (Rogers Covey-Crump, tenor; Jakob Lindberg, lute)

It’s not just a song for men, here, the soprano Emma Kirkby takes on the text, with the lute part augmented by a viol consort. She adds a bit of ornamentation as might have been added at the time. Listen, in particular, for how she says ‘hell’ at the end.

John Dowland: Book of Songs, Book 2 – Flow my tears (Emma Kirkby, soprano; Chelys Consort of Viols; James Akers, lute)

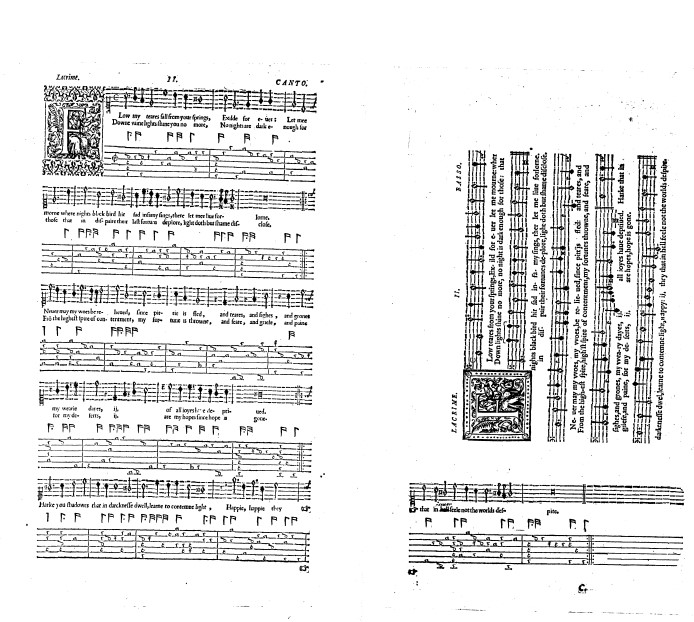

However, when we go back to the original score, we see that it was actually written for two voices, given here as ‘Cantus’ and ‘Bassus.’

Book of Songs, Book 2 (1600): Flow, my tears, fall from your springs

This makes the song much more than a single statement of unhappiness, but more of a universal unhappiness. This utter despair in love will affect everyone at some point in their life.

Sung as a duet with lute, the song seems to deepen in its meaning. The cantus takes the melody, but the bass seems to be both supporting her song and yet adding in his own sadness.

John Dowland: Book of Songs, Book 2 – Flow, my tears, fall from your springs (Ruby Hughes, soprano; Alain Buet, bass; Thomas Dunford, lute)

Listening to different recordings of this song sung from 1953 (Deller) to 2016 (Hughes/Buet) let us appreciate how reading this song and performing this song have changed over the past 60 years. Performers are no longer afraid to make them passionate performances and also bring their own ornamentation and dynamics into the techniques they apply. There’s nothing as wonderful as hearing a work you know well in a new performance that lets you hear the work anew.

Dowland’s work in Denmark ended in 1606 and he returned to England, where he had always published his music. In 1612 he finally achieved his desire and was appointed as lutenist to James I and he held the post until his death in 1626.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter