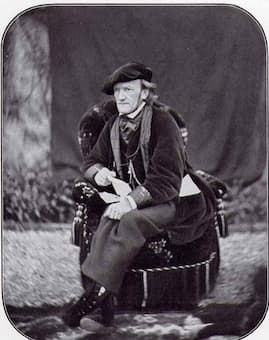

Richard Wagner, 1868

Richard Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg premiered, generously supported by Ludwig II of Bavaria, at the Munich Court Opera on 21 June 1868. Hans von Bülow conducted, and Franz Strauss, the father of Richard Strauss played the French horn at the premiere. It was enthusiastically received, and Eduard Hanslick wrote in Die Neue Freie Presse, “Dazzling scenes of color and splendor, ensembles full of life and character unfold before the spectator’s eyes, hardly allowing him the leisure to weigh how much and how little of these effects is of musical origin.” Within a year of its premiere, Meistersinger was performed across central Europe, and Hans Sachs’s final warning at the end of Act III for the need to preserve German art from foreign threats became a rallying point for German nationalism, particularly during the Franco-Prussian War, the Wilhelmine Reich, the Weimar Republic, and most notoriously, during the Third Reich.

Richard Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

This essentially good-natured comic parable about the relationship between art and those that create it, Meistersinger is unique among Wagner’s mature operas as it is set in a historically well-defined time and place rather than a mythical or legendary setting. It takes its inspiration from the Renaissance guild of Meistersinger (Master Singers) active during the 16th century in the imperial city of Nuremberg.

Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger “Overture”

In the Metropolitan Opera House : scene from Die Meistersinger. (1898)

The origins of Meistersinger dates back to July 1845, when Wagner, battling acute exhaustion, professional rejection and financial destitution, took a cure at the famous Marienbad spa in Bohemia. Under strict orders from his doctors to abstain from creative work, Wagner opted for a close reading of the History of German Literature by Georg Gottfried Gervinus. Wagner later wrote, “From reading Gervinus, I had formed a particularly vivid picture of Hans Sachs and the mastersingers of Nuremberg. I was especially intrigued by the institution of the Verse-marker and his function in rating master-songs. Without yet knowing anything more about Hans Sachs and his poetic contemporaries, I conceived during a walk a comic scene in which the popular artisan-poet, by hammering upon his cobbler’s last, gives the Marker, who is obliged by circumstances to sing in his presence, his come-uppance for previous pedantic misdeeds during official singing contests, by inflicting upon him a lesson of his own…To this picture I now added a narrow, twisting Nuremberg alley, with neighbors, uproar and street-fight, and suddenly my whole mastersingers comedy stood before me so vividly that, on the grounds that it was an especially merry subject, I felt justified in putting it on paper despite the doctor’s instructions.”

Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger, Act III “Selig, wie die Sonne”

Wagner: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg Act III

Political, personal and musical circumstances intervened, and Meistersinger completely disappeared from radar for more than a decade. However, severely depressed after the notorious Tannhäuser fiasco in Paris in March 1861, Wagner writes to his publisher Franz Schott, “I feel that I need a break from the very real seriousness of my everyday preoccupations in order to create something quickly that will bring me into more immediate contact with the practicalities of our contemporary theaters.” He even suggested that he would be able to deliver the score “finished and ready for performance by next winter.” In the event, it would take Wagner another six years to complete Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Over the nearly two decades of gestation, the potential of the Meistersinger material and the character of Hans Sachs had undergone significant changes. Of particular importance to Wagner’s re- evaluation were the philosophies of Arthur Schopenhauer who suggested, “Art was a means for escaping from the sufferings of the world,” and “that music is the highest of the arts since it is the only one not involved in representation of the world.” Instead of the envisioned thoroughly light and popular libretto, Wagner’s final text weaves together a literary fabric drawn from a wide array of sources that serves as a universal metaphor for the human condition.

Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger Act III “Prize Song”

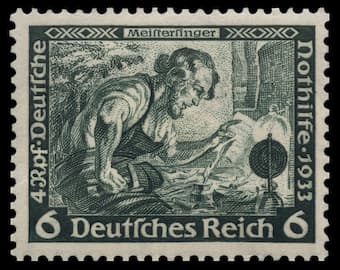

Wagner’s Meistersinger stamp

Theatrical, textual and philosophical considerations aside, Wagner had to find the right musical language to express a milieu that, while inspired by a specific historical setting, was ultimately a thoroughly reimagined world far removed from Renaissance Nuremberg. More than any other creation by Wagner, Meistersinger is about music itself. Wagner was particularly concerned with music’s ability to express and convey an entire range of sentiments located deeply below the surface text sung by the characters. This meta-musical aspect encompasses a remarkable spectrum, from complex ensembles to the psychological intimacy of the portrait of “Sachs” in the third act. The effectiveness of Wagner’s process, as has been pointed out, is to keep moving our focus “from the outside—consideration of the whole monumental work—to areas within.” The score is a sublime artistic achievement, at once lyric, grand and amazingly detailed. As a critic wrote, by any purely artistic assessment, “Die Meistersinger is a finely crafted drama, rich with dramatic and musical textures that showcase Wagner’s creative gifts at their best.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger, Finale