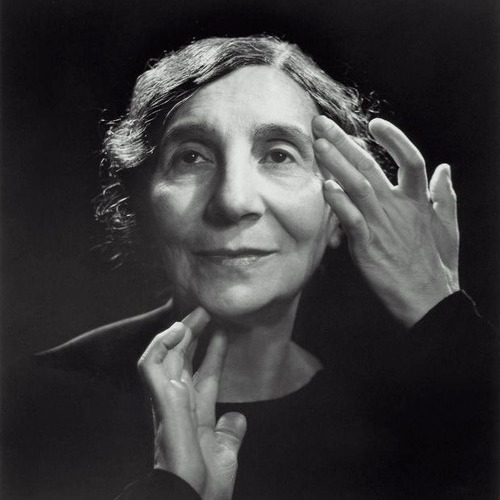

Wanda Landowska, 1937

Wanda Aleksandra Landowska, born to Jewish parents in Warsaw on 5 July 1879, played a seminal role in reviving the popularity of the harpsichord in the early 20th century. A champion of 17th and 18th-century music and the leading figure in the revival of the harpsichord, Landowska was the first person to record Bach’s Goldberg Variations on that instrument in 1933. Landowska grew up in an environment that nurtured her musical talent. Her father was a lawyer while her mother spoke six languages and first translated Mark Twain into Polish. She took piano lessons at the age of four with Jan Kleczyński and subsequently, with Aleksander Michałowski at the Warsaw Conservatory. Her assistant remembered, “As a little girl her teachers were Chopin players, and she was first educated in that school of playing. But from a very early age, her personal taste was for music of older times. She once heard a pianist play a piece by Rameau, which was very rare in those times, and she was fascinated, she loved it. Her teachers realized that she was really a musical genius and that they should not impose on her too much.”

Wanda Landowska Plays Bach’s Goldberg Variations 1933

Caricature of Landowska, 1930

Wanda’s mother considered her first teacher Klenczynski too lenient, explaining that “he would let her do anything she wanted and her education should not be done that way.” By all accounts, Michalowski was much stricter with her, but he also let her play Bach. “These men,” according to Wanda’s assistant, “did not know the real interpretation of Bach. It was a time when the Bach tradition was gone.” Landowska developed into a formidable Chopin player, “and people would have given anything to have her record or play Chopin more often.” However, as a close friend wrote, “There was a conflict in the way she was brought up in the late Romantic tradition but desperately wanting to do something else, that is, to go back to the old masters.” However, at the age of sixteen a small growth developed in her hand, casting her career in doubt. And while Landowska briefly contemplated a career as a singer, her mother sent her to Berlin in 1896 to study composition with Heinrich Urban, who had been the teacher of Paderewski. Her time in Berlin was, in her own words, “refractory to rules,” but she did compose a number of songs for voice and piano and “Paysage triste” for string orchestra.

Wanda Landowska: Reverie D’Automne (Jeanne Golan, piano)

Leonid Pasternak: Concert of Wanda Landowska in Moscow

Landowska won two prizes in 1903 in the “Musica International Competition” with a piano piece and a song, causing Massenet to declare “Elle a du talent, beaucoup de talent.” During her time in Berlin her hand ailment improved significantly, and she was once again able to play the piano. She also met the young Polish writer Henry Lew, soon to be an authority on Hebrew folklore. At the suggestion of Henry, they moved to Paris and got married. Taking piano lessons with Moritz Moszkowski, Landowska was also introduced to the “Schola Cantorum” and met Vincent D’Indy and all the great musicologists of the day. Landowska became part of the circle of scholarship that enthusiastically researched 17th-and 18th-century music and its interpretations. Her initial interest was drawn to Bach Cantatas, the Passions and orchestral works. She was also introduced to French Music, to Couperin and Rameau. “Gradually she realized that the piano was not the right instrument for that type of music, and she visited all the museums in Europe with old instruments. She even took the chief engineer of Pleyel with her to take notes and measurements of instruments in Brussels, in Leipzig, and in England.”

Wanda Landowska Plays Bach (1953)

Postcard of Wanda Landowska

Landowska played her first harpsichord recital in public in 1903 and subsequently undertook concert tours in Europe. This included a highly successful tour of Russia in 1907 where she met Leo Tolstoy for the first time. Concordantly, Landowska was assiduously writing what she herself later called “belligerent articles to overcome the resistance widely shown towards the harpsichord, largely on account of the feeble tone of the available instruments.” And in 1909 she published her book Musique ancienne, and three years later at the Breslau Bach Festival triumphantly introduced a large new two-manual harpsichord built to her own specification by Pleyel.

Landowska with Leo Tolstoy, 1907

Landowska’s decision to revive harpsichord music was by no means uncontested. Her performances were received skeptically, and she wrote in her autobiography, “anyone who heard me as a pianist was worried that I might neglect the piano in favor of the old Joanna.” Joanna in this case, is a sexist slant that assumes that the powerful music of Johann Sebastian will be turned into a feeble feminine by the supposedly weak tone of the harpsichord. And she would publically defend herself by writing, “it is true that the harpsichord still has many stubborn opponents, but most of these consist of piano teachers and old-style virtuosi.” Francis Poulenc, for one never objected, and while composing the commissioned Concert champêtre, he wrote. “You know what an amazing artist Wanda Landowska is. The way in which she’s revived the harpsichord, or renovated it if you prefer, is simply miraculous.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wanda Landowska Plays Poulenc’s Concert champêtre