While the war years provided much opportunity for stirring patriotic films, the industry underwent a number of significant changes immediately following. With money in short supply, the lush symphonic scores of the Golden Age gradually declined, and composers started to explore new musical styles. This included the use of popular music genres as well as 20th century art music.

Bernard Herrmann: Psycho

Psycho

Bernard Herrmann was an early pioneer, and he is “widely regarded as one of the greatest film composers in the history of this medium.” In his first film score Citizen Kane produced for Orson Welles in 1941, Herrmann creates a seriously dark atmosphere by relying on low instrumental colors and tone clusters. These early experiments with modernism in film music seemed particularly well suited for the entire thriller genre.

Bernard Herrmann

As such, Herrmann became known for his collaborations with director Alfred Hitchcock. Hitchcock was not a composer, but he had “an intense understanding of the crucial partnership between the cinematic image and the aura created by music. He knew that cinema and music create an alchemy of experience and that each story requires a unique music to tell that story.” In his score for Psycho, Herrmann only used string instruments, but he “makes use of every technique in playing those instruments, arco, pizzicato, muted, tremolo, harmonics, col legno battuta, etc. to create a world of black-and-white terror.”

Bernard Herrmann: Psycho (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Bernard Herrmann, cond.)

Miklós Rózsa: Ben-Hur

Ben-Hur

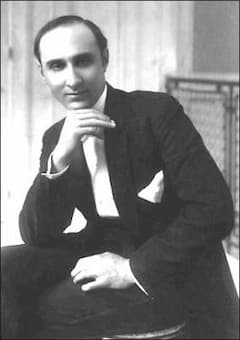

While thrillers demanded their own unique style of music to assist with tension building and creating a number of false alarms to shock audiences, epic and historical dramas required music on a much grander scale. Miklós Rózsa, a Hungarian-American composer who had trained in Germany and worked in France, the United Kingdom and the United States, Rózsa had made his name composing concert music, with his compositions championed by such major artists as Jascha Heifetz, Gregor Piatigorsky, and János Starker. After Rózsa became an American citizen in 1946 he composed the music for nearly 100 films.

Miklós Rózsa

He is probably best remembered for his score to the religious epic Ben Hur. Based on a novel by Lew Wallace, it tells the story of a fictitious aristocratic Jew living in Judaea who incurs the wrath of a childhood friend, now a Roman tribune. The film, first screened in 1959, won a record 11 Oscars, and everybody loves the most memorable sequences of the sea battle and the chariot race. In preparation for the film Rózsa researched Greek and Roman music, searching for musical authenticity in a track of over three hours of music. “While the score contains no leitmotifs, the music always transitions from full orchestra to pipe organ whenever Jesus Christ appears.” This particular soundtrack was hugely influential well into the mid 1970s, and spawned a huge film music following.

Miklós Rózsa: Ben-Hur (North Hungarian Symphony Orchestra; László Kovács, cond.)

Aaron Copland: The Heiress Suite

The Heiress

As the film industry warmed to the idea of including more daring musical sounds in films, “several prominent American composers of art music turned their attention to the genre. The famous Aaron Copland wrote music for five Hollywood feature films and received a total of four Oscar nominations. Copland won the Award for Best Music, Original Score, in 1949 for The Heiress after a novel by James Joyce. The renowned actress Olivia de Havilland, who fell in love with the Broadway play, instigated this particular film project. She approached director William Wyler, and he in turn, immediately passed a copy of the script to Aaron Copland.

Copland and Milhaud in 1949

Copland replied, “The picture will not call for a great deal of music, but what music it does have ought to really count. I can see that the music would be a valuable ally in underlining psychological subtleties… That atmosphere, as I see it, would produce music of a certain discretion and refinement in the expression of sentiments.” In his music, Copland focused on the underlying unspoken emotions unfolding beneath the surface action. He employed a small ensemble orchestra and decided on a system of leitmotifs, and he relies on five primary themes, which include two love themes. A critic writes, “Copland’s genius is on full display in the soundtrack but also in the context of the film.”

Aaron Copland: The Heiress Suite (St. Louis Symphony Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Leonard Bernstein: On the Waterfront Suite

Leonard Bernstein, 1950s

Copland’s colleague Leonard Bernstein composed original music for a single movie, the Elia Kazan masterpiece On the Waterfront of 1954. Starring a young Marlon Brando, Eva-Marie Saint and a surplus of stars, the Academy Award-winning movie is widely considered one of the greatest films of all time. Bernstein initially rejected the offer to compose a film score, because Kazan had given notorious statements against “un-American activities.” However, impressed by Brando’s performance, Bernstein spent four months composing the score.

Elia Kazan

Bernstein explained, “I heard music as I watched the rough cut, and that was enough. The atmosphere of talent that this film gave off was exactly the atmosphere in which I love to work and collaborate… Day after day I sat at a moviola, running the print back and forth, measuring in feet the sequences I had chosen for the music, converting feet into seconds by mathematical formula, making homemade cue sheets.” Bernstein did find the process stimulation, but frequently found the experience confining. He wrote to Aaron Copland, “Hollywood is exactly how I expected it, only worse.” The symphonic construction of the score is really audible in the six-movement suite from the film that Bernstein fashioned the following year. His score supporting this tale of corruption and redemption with a mixture of modern and jazz elements, featuring “one of the most powerful and finest moments in film history.”

Leonard Bernstein: On the Waterfront Suite (Nicolas Prost, saxophone; Claude Collet, piano; Jean-Francois Durez, drums; Lamoureux Orchestra; Yutaka Sado, cond.)

Dmitri Tiomkin: Nigh Noon (Ballad of High Noon)

High Noon

The period after the great Wars established a highly popular genre of film called the “Western.” Stories centered on the life of nomadic drifters, cowboys or gunfighters interacting with harsh wilderness, desolate landscapes and villains. In fact, the American Film Institute defines Western films as those “set in the American West that embody the spirit, the struggle, and the demise of the new frontier.” Wrongs are frequently righted by shootouts or quick-draw duels. The “Western” genre also brought a revolution in terms of film music, and Dmitri Tiomkin was the undisputed master working in that genre.

Dmitri Tiomkin

Born in Russia and classically trained in St. Petersburg, Tiomkin moved to Berlin and then New York City after the Russian Revolution. Following the stock market crash in 1929, he moved to Hollywood and became famous for his scores for Western films. In fact, he received a total of 22 Academy Award nominations, and won four Oscars. In 1952 Tiomkin created a landmark score for the Western High Noon, incorporating a country/western ballad sung by Tex Ritter. Tiomkin used the ballad in both the opening credits and during scenes showing the isolation of Sheriff Will Kane. “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darling” created a seminal event in film score history and a public sensation. According to experts, it established the “theme-song craze in film scores. “Henceforth songs written specifically for films, as opposed to using preexisting source songs, came to dominate modern film. To this day studios attempt to add a hit song to the soundtrack to enhance the movie experience and profits should the song resonate with popular culture.”

Simon & Garfunkel: “Sound of Silence” (The Graduate)

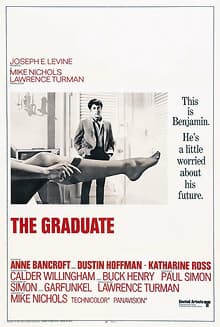

The Graduate

Not entirely unexpected, rock music came of age with Hollywood movies. The 1955 release of The Blackboard Jungle featured “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and the Comets. It propelled the song to the top of the charts and marked the beginning of the Rock era. Such unlikely artists as Elvis Presley became movie stars, who made “pictures at the rate of three a year for nearly a decade.” The Graduate of 1967 was a landmark film directed by Mike Nichols. It tells the story of 21-year-old Benjamin Braddock portrayed by Dustin Hoffman, a recent college graduate with no well-defined aim in life. He is seduced by an older married woman named Mrs. Robinson and played by Anne Bancroft. However, he then falls in love with her daughter Elaine, played by Katharine Ross.

Simon & Garfunkel, 1968

For his soundtrack, Mike Nichols relied almost entirely on licensing songs that had little to do with the film itself. It certainly boosted the profile of folk-rock duo Simon & Garfunkel. While their song “The Sound of Silence” was used originally as a pacing devise for the editing, it was eventually included in the soundtrack. The film’s only original song “Mrs. Robinson” stormed the charts and it became the first rock song to win the Grammy Award for Record of the Year. A scholar writes, “this practice continues to influence Hollywood’s approach to film music for decades. The ancillary income opportunity of soundtrack sales in combination with the fact that it’s cheaper to score a film with songs made this method a highly attractive strategy for studios.”

Miles Davis: Ascenseur pour L’Échafaud, “Nuit Sur Les Champs-Élysées”

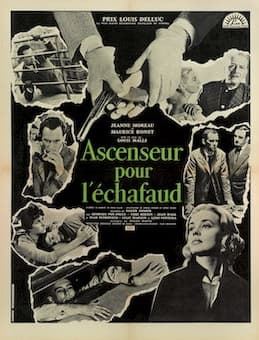

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud

(Elevator to the Gallows)

In 1946, the French film critic Nino Frank noticed a trend of “ dark, downbeat and gloomy looks and themes in American crime and detective films released during and following World War II.” These films reflected the tensions and insecurities of the time period, “and counter-balanced the optimism of Hollywood musicals and comedies.” Termed “Film Noir” these black and white movies reveled in feelings of fear, mistrust, bleakness, loss of innocence, despair and paranoia with the threat of nuclear annihilation ever-present. A scholar writes, “strictly speaking, film noir is not a genre, but rather the mood, style, point-of-view, or tone of a film.”

Miles Davis

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) was a 1958 film noir directed by Louis Malle, starring Jeanne Moreau and Maurice Ronet as illicit lovers whose murder plot unravels after one of them becomes trapped in an elevator. But the groundbreaking element of the film was the fact that the great Miles Davis was asked to improvise the soundtrack. Davis had been performing at the Club Saint-Germain in Paris during November 1957. Introduced to the director, Davis agreed to record the music after attending a private screening. He brought his four sidemen to the recording studio without have had them prepare anything. He simply gave the musicians some rudimentary harmonic sequences, explained the plot, and then the band started to improvise, pure genius.

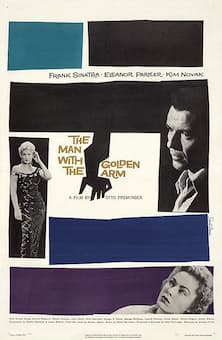

Elmer Bernstein: The Man with the Golden Arm Suite

The Man with the Golden Arm

In the post-war environment of film music, composers needed to be versatile and be able to write in all musical styles, including modern and popular. Elmer Bernstein writes, “I think that the composer is in a somewhat better position now than he has been in for some time. The attitudes appear to be a little bit looser, less doctrinaire on the part of the producers. There was one time a feeling… that they wanted either a rock score or a commercial score.” Bernstein’s career spanned more than five decades, and he composed “some of the most recognizable and memorable themes in Hollywood history.” He has received countless awards for his over 150 original film scores, as well as scores for nearly 80 television productions.

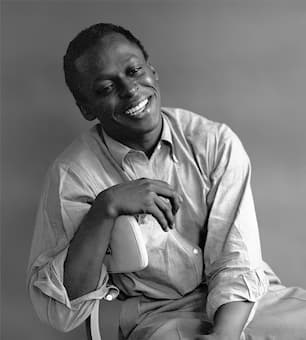

Elmer Bernstein

Bernstein is one of the finest craftsmen from the post-war era, and he helped to introduce jazz as underscoring in the 1955 film The Man with the Golden Arm. Directed by Otto Preminger, it starred Frank Sinatra, Eleanor Parker, Kim Novak, Arnold Stang, and Darren McGavin. The plot focuses on the story of a drug addict who gets clean while in prison, but struggles to stay that way in the outside world. The film was highly controversial for its treatment of the subject of drug addiction, and Bernstein’s underscoring provided a vivid portrayal of this subject. Bernstein subsequently went on to score blockbusters like The Magnificent Seven, To Kill a Mockingbird, Ghostbusters, Wild Wild West, and many others.

Elmer Bernstein: The Man with the Golden Arm Suite (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Richard Bernas, cond.)

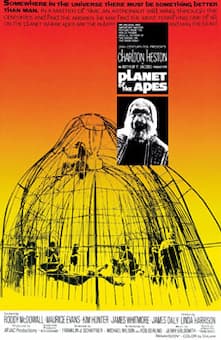

Jerry Goldsmith: Planet of the Apes

Planet of the Apes

I want to conclude this blog by featuring the composer and conductor Jerrald King Goldsmith, famous for his work in film and television scoring. He composed scores for five films in the Star Trek franchise and three in the Rambo franchise, as well as for Patton, Chinatown, Alien, Poltergeist, Gremlins, Hoosiers, Total Recall, Air Force One, L.A. Confidential, Mulan, The Mummy, and Planet of the Apes.

Jerry Goldsmith

The original 1968 movie starred Charlton Heston as the American astronaut George Taylor, who travels to a strange planet where intelligent apes dominate mute, primitive humans. The finale, in which Taylor comes upon a ruined Statue of Liberty and realizes he has been on Earth all along, “became the series defining scene and one of the most iconic images in 1960s film.” For his musical score, Goldsmith took an experimental approach “that relied heavily on avant-garde, tribal-sounding percussion, and ethereal strings.” As a critic wrote, “it is a terrifying and starling score in its sparseness as there is tremendous space provided for silence within the music.” Please join me next time for a concluding episode featuring the greatest composers of film music, including John Williams, Danny Elfman, Hans Zimmer, Rachel Portman, and Tan Dun.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter