Popular for just over a century, the Bourrée or Bourée started as a folk dance in the mid–17th century but upon its adoption by the Academie of Dance at the French court (the Academie was established by Louis XIV in 1661) it entered the world of society. It faded from view again in the mid-18th century but continues to pop up occasionally.

Michael Praetorius, who preserved many dances from the French court in his collection Terpsichore, also collected the bourrée. One of the characteristics of the form is its quarter-measure pickup, starting a note before the main beat.

Michael Praetorius: Terpsichore – La Bourée (London Early Music Consort; David Munrow, cond.)

© luisdias.wordpress.com

As a dance, it starts with an initial movement, a plié (where the knee is bent while the body is held upright) on the supporting leg, followed by three changes of weight on the legs during the measure – from this simple beginning, many variations were created over the century.

Robert de Visée, lutenist and guitarist at the courts of Louis XIV and XV, created bourrées for solo lute or for small ensembles.

Robert de Visée: Pieces de theorbe et de luth mises en partition dessus et basse – Suite in D Major: VI. Bourree, “La Villageoise” (Manuel Staropoli, recorder; Massimo Marchese, theorbo; Rosita Ippolito, viola da gamba; Manuel Tomadin, harpsichord)

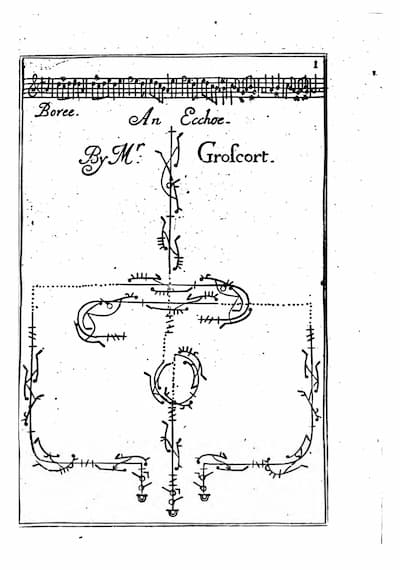

Here’s the first of many pages of dance notation for the Bourrée, this one designed by M. Groscort, given in the notation designed by Feuillet of the French Academie of Dance. Since the music is given above the notation, the dancer can follow with the music, as the measures are marked across the center line. The emphasis of this notation was the footwork. If you want to see what this all means, it was given in English translation in 1706.

Pemberton: An essay for the further improvement of dancing; being a collection of figure dances, of several numbers, compos’d by the most eminent masters: The Boree, 1711

The first minute of this video gives an example of the bourrée step, described in this dance as “one-two-three-dip” done as gracefully as you can.

Example of Bourrée Step

We have bourrées in the music of the great Baroque composers, including J.S. Bach.

J.S. Bach: Lute Suite in E Minor, BWV 996 – V. Bourrée (Hopkinson Smith lute)

Handel included bourées in both his Water Music and Royal Fireworks sets.

George Frideric Handel: Water Music – Suite No. 1 in F Major, HWV 348 – VIII. Bourree (Aradia Ensemble; Kevin Mallon, cond.)

In the 19th century, Chopin wrote bourrées.

Frédéric Chopin: Bourrée I (Idil Biret, piano)

In 1891, Emmanuel Chabrier wrote La bourrée fantasque with a very Spanish flavour. It was originally written for piano, but has had a wider reception in its orchestral form, as arranged by Chabrier’s friend, the conductor Felix Mottl.

Emmanuel Chabrier: Bourrée fantasque (version for orchestra) (Orchestre des Champs-Élysées; Paul Bonneau, cond.)

We can hear the former single note upbeat transformed into two quick notes, and Chabrier’s fantastic vision has lifted the bourrée out of the Baroque and into the modern world. Chopin’s Bourrée, on the other hand, still has dance-like qualities.

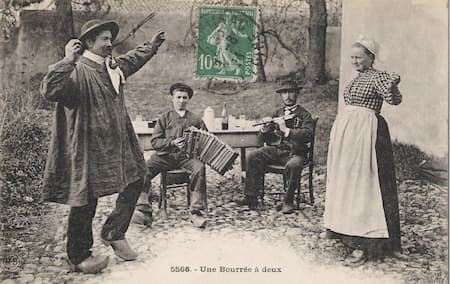

Bourrée in Auvernia, early 20th century © Wikipedia

The movement of the bourrée into the 20th century was encompassed by the world of pop music. Paul McCartney said that his song ‘Blackbird’ was inspired by Bach’s Bourrée (BWV 996) and Bach’s original was also covered by the groups Bakerloo (Drivin’ Bachwards) and Jethro Tull (Bourée).

Jethro Tull: Bourée (1969)

It’s interesting to see how a dance comes in and out of popularity. The bourrée’s origins in peasant music from the Auvergne and its adoption by the French court gave it distinct French credentials. Even in the late 19th century, Chopin’s Bourrée was summoning up the feeling of the French court but in Chabrier’s reworking of the genre, he has taken us out of the court and deposited us in the realm of the fantastic. The use of the bourrée in 20th century pop music is a surprise, but at the same time, we shouldn’t underestimate the importance that Bach’s music has had in influencing pop culture.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter