The 20th century normalized doctors – we now see them in their more accustomed roles as healers or consultants to the ill. The occasional black magician / doctor still appears, but that role is increasingly rare.

We open the century with Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, where in the last act, the ailing Mélisande, having had her abnormally small baby, is attended by a doctor, and she ‘dies without realizing that she is dying.’

Pelléas et Mélisande (Opera Ballet Vlaanderen)

Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande – Act V: Une chambre dans le chateau (Jean-Jacques Doumene, A Doctor; Gabriel Bacquier, Arkel; Armand Arapian, Golaud; Mireille Delunsch, Mélisande; Lille National Orchestra; Jean-Claude Casadesus, cond.)

In Richard Strauss’ glorious farewell to the 19th century, Der Rosenkavalier, an incidental role is given to a physician who comes to tend Baron Ochs after he has been wounded; it’s a silent role with his duties conveyed by gestures.

Franz Schreker’s Der Ferne Klang (The Distant Sound) was important in establishing Schreker’s career. Fritz is off to search the world for ‘the distant sound.’ He hears it in his heart and for him, it represents all that he will be or will have: artistic achievement, fame, fortune. He leaves his girlfriend Grete, to find this and when he has done so, will return to marry her. However, her drunk father has lost her in a bar game, promising her to the Innkeeper. Everyone’s life changes. Fritz becomes a famous composer, Grete flees her father’s bet and in the big city, becomes a famous madam and then a street prostitute. At the end of the opera, Rudolf, a doctor and Fritz’ friend, tries to get him to finish his last opera. Fritz realizes that ‘the distant sound’ that he looked so hard for was the sound of nature itself and surrounds him all the time. Fritz and Grete are reunited and he dies in her arms.

Franz Schreker: Der ferne Klang – Act III Scenes 14-15: Fritz! Fritz! – Hast Du mir verziehn? (Thomas Harper, Fritz; Elena Grigorescu, Grete; Hagen Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Halász, cond.)

The French playwright Molière’s 1665 comédie-ballet L’amour médecin was set to music originally by Lully. It was taken up in the 19th century by Ferdinand Poise in 1880 and then, most memorably, by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari in 1913. Lucinda (soprano), to avoid her father’s choice of husband, develops a debilitating illness. Lucinda’s maid identifies her illness as the need for a husband, but the series of doctors who are called in don’t agree. They (a tenor, 2 baritones, and a bass) have conflicting ideas and contradict each other. The maid, however, has found a new doctor, Clitandro (tenor), who brings Lucinda out of her illness by pretending to woo her. They marry as part of her treatment and only then does her father find out that not only was it a real marriage but also that he’s promised them a large dowry.

Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari: L’amore medico: Overture (Oviedo Filarmonía; Friedrich Haider, cond.)

Gianni Schicchi was Giacomo Puccini’s 1918 one-act opera, introduced at the Metropolitan Opera in New York as the third part of Il Trttico. Dr Spinelloccio (bass) is called into diagnose the wealthy Buoso but gets fooled by Gianni Schicci.

In Eugen d’Albert’s Die toten Augen (The Dead Eyes), Myrtocle, the wife of Arcesius, has been blind from birth and wants to be able to see so that she can gaze upon her husband, who she believes is as handsome as Apollo. Many doctors have tried to cure her, including Ktesiphar (tenor), an Egyptian doctor, but have failed. Finally, Christ (in a single off-stage sentence) restores her sight and she falls into the arms of the man she believes is her husband because he is so handsome. Unfortunately, it’s her ugly huband’s best friend Aurelius Galba, and the outraged husband kills him. Mytocle, understanding her husband’s love and the suffering that her sight has brought him, blinds herself again by looking into the sun.

Eugen d’ Albert: Die toten Augen: Herrin, da kommt Ktesiphar (Margaret Chalker, Arsinoe; Dagmar Schellenberger, Mytocle; Eberhard Büchner, Ktesiphar; Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra; Ralf Weikert, cond.)

Sergei Prokofiev’s commedia dell‘arte–based opera The Love for Three Oranges was commissioned in 1918 during Prokofiev’s first visit to the US. Prokofiev combined commedia dell’arte elements with surrealism in his realization, turning the last of the princesses imprisoned in the oranges into a rat (evil machinations by a jealous other).

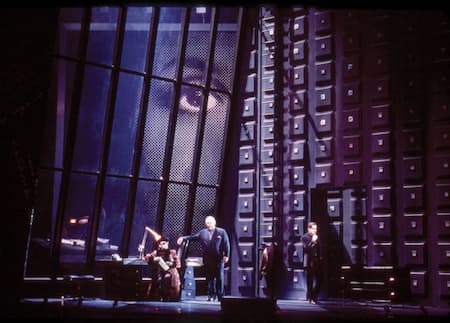

The Love for Three Oranges, 2005 (Opera Bastille)

The King of Clubs is looking for a solution to his son Leandro’s hypochondria or ‘galloping malingeritis’, and none of the doctors has a cure. In their consultation, the doctors tell the King the worst: his ‘Liver’s gone to pot, kidneys turned to stone, skin is too hot and too near the bone and same with his humour, he’s gone harder in the arteries, softer in the head, his voice has gone treble, his vision is double…’ and so on. He can only be cured by laughter, until he laughs at the wrong thing and the sorceress Fata Morgana curses him with a ‘love for three oranges.’ In the end, the princess is turned back from being a rat and Fata Morgana and the bad guys escape through a trapdoor in the floor.

Sergei Prokofiev: The Love for Three Oranges, Op. 33 – Act I Scene 1: Oh, poor boy! Tell me the worst. What are his chances? (Bruce Martin, The King of Clubs; Warwick Fyfe, Pantaloon; Opera Australia Chorus, Doctors and Eccentrics; Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

In Umberto Giordano’s 1924 La cena delle beffe (The Supper of Jest) the doctor suggests that Neri be mocked by his previous victims as a way of restoring his sanity.

Ferruccio Busoni contributed his 1925 Doktor Faust to the list of Faust operas.

Wozzeck, which received its premiere at the Berlin Staatsoper in December 1925 has the role of the Doctor (buffo bass) as one of the cruel persecutors of Wozzeck. Alban Berg created much of the lead character and his miserable situation out of his own experience in WWI, writing to his wife in 1918, ‘There is a little bit of me in his character, since I have been spending these war years just as dependent on people I hate, have been in chains, sick, captive, resigned, in fact, humiliated.’ In Act 1, scene 4, we are introduced to the Doctor, who rejoices at Wozzeck’s mental aberrations that result from the diet and training regime he has given him.

Alban Berg: Wozzeck, Op. 7 – Act I Scene 4: Was erleb’ ich, Wozzeck? (Alexander Malta, The Doctor; Eberhard Waechter, Wozzeck; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Christoph von Dohnányi, cond.)

In act 2, scene 2, the Doctor and the Captain meet in the street

Alban Berg: Wozzeck, Op. 7 – Act II Scene 2: Wohin so eilig (Alexander Malta, The Doctor; Heinz Zednik, The Captain; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Christoph von Dohnányi, cond.)

Wozzeck marks a new view of the physician in opera. He’s an active participant and is presented in a much more personal way. We learn a great deal about his character through the opera, including the terrible scene in the final act when he hears Wozzeck drowning and hurries away. He’s not a physician of comfort and healing, he’s one of experimentation and fear. He’s the doctor for the modern age, as experienced by the composer in his own life.

Simon Keenlyside as Wozzeck and John Tomlinson as the Doctor, 2013 (Royal Opera House)

(Photo by Catherine Ashmore)

The Doctor made another appearance in Manfred Gurlitt’s successful version of Wozzeck in its Bremen production in 1926. The two composers worked separately and produced their operas within 4 months of each other. Gurlitt took Buchner’s fragmented text and created 18 scenes, without ordering it into acts like Berg. Berg’s version has eclipsed Gurlitt’s but each opera has its own aesthetic. Berg’s is considered closer to Wagner, while Gurlitt followed the more populist models of Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill. You can hear the difference comparing this scene with the one above by Berg.

Manfred Gurlitt: Wozzeck, Op. 16: Scene 6: Wohin so eilig (Anton Scharinger, The Captain; Robert Wörle, The Doctor; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Gerd Albrecht, cond.)

The Doctor in Leoš Janáček’s The Makropulos Affair has only a silent role, appearing in the final act as a support to the singer, Emilia Marty (or is that Eugenia Montez, Elsa Müller, Ellian MacGregor, Ekaterina Myskina, or any of the other manifestations of Elina Makropulos over the past 300+ years?). Dr Kolanaty at the beginning of the opera is a lawyer.

Opening Scene of The Makropulos Affair, 2001 (Metropolitan Opera)

Sergei Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel has a physician’s role (baritone) but it’s not a prominent part.

The final 20th century opera we’ll look at in this section is Dimitri Shostakovich’s satirical take on Nikolai Gogol’s story of nearly a century earlier. In Gogol’s 1836 story, Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov’s nose has left him, grows to human size, and develops its own life, a life that is more successful than Kovalyov’s own. In Part 2 of the story, the Nose, which was caught at the bus station trying to flee the city, is returned to Kovalyov, but, even with the aid of a doctor, he is unable to reattach it. By the end of the story, all is back to normal, Kovalyov’s nose is back in place.

Dimitri Shostakovich: Nos (The Nose), Op. 15 – Act I: Galop (St. Petersburg Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra; Valery Gergiev, cond.)

The Nose, 2013 (Metropolitan Opera)

The work was Shostakovich’s first opera, completed in 1928. Its premiere was given in Leningrad in 1930 and after its 16-performance run, and then largely vanished from the performance stage until the conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensy turned up a copy at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1974. His 1975 recording was made in Moscow, with the oversight of the composer.

Even in the first 30 years of the 20th century, we can see a difference in how doctors are portrayed. They are much more central and serious characters. Rather than just being walk-on characters, they now serve to drive and direct the plot, often to the detriment of the main character.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter