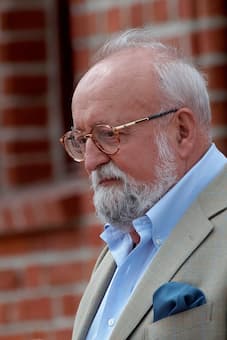

Krzysztof Penderecki, 2008

The Stuttgart Liederhalle witnessed an unusual premiere performance on 28 September 1984. It featured a Russian conductor, a German choir and orchestra, an American soprano, a German mezzo-soprano, a Polish tenor, and a British bass. They had gathered to present the first performance of the Polish Requiem by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki. Penderecki has been called “a composer with a social conscience,” and his tendency to relate his musical works to political and social events in history is amply demonstrated in a variety of works, ranging from his Threnody to the Dies Irae and The Devils of Loudun.

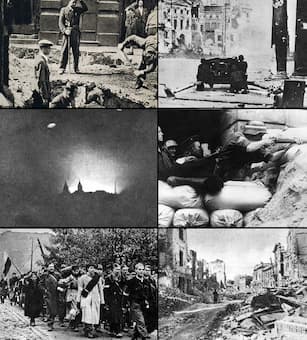

Warsaw in 1944

In one interview, Penderecki defines the goal of musical arts as “the restoration of the sacred dimension of reality.” In essence, the composer is looking for a renewed bond between the artist and the audience and seeks to overcome the notion that art is to be understood as an object of aesthetic value alone.

Krzysztof Penderecki: Polish Requiem “Lacrimosa” (Stockholm Royal Philharmonic Choir; Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra; Krzysztof Penderecki, cond.)

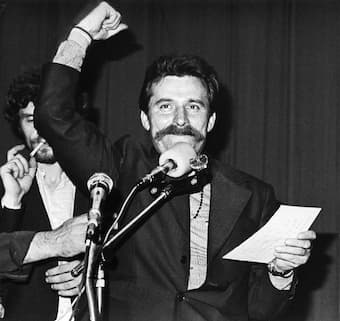

Lech Walesa, 1980

The title Polish Requiem arose from the desire of the composer “to dedicate certain parts of the work to particular events or personalities in the recent history of Poland, a period the composer calls a very turbulent time in our history.” To be sure, the Polish Requiem had been on the composer’s mind for a number of years. The first section to be completed was the “Lacrimosa” composed in 1980 for Lech Walesa and his trade union Solidarity as an in memoriam for the Gdansk dock-workers who died during confrontations with the authorities ten years earlier.

Stefan Wyszyński

Penderecki explained, “Without the overall political situation, without Solidarity, I would not have written the Requiem, even though I had long been interested in the subject. When composing the Requiem, I wanted to take a specific position, to say which side had my support.” Written under a period of martial law, the Requiem was intended to “cheer people’s hearts.”

Penderecki next composed the “Agnus Dei” in 1981 as a memorial tribute to Stefan Wyszyński, for many the unquestionable spiritual leader of the Polish nation. The Cardinal openly preached his opposition to the totalitarian communist government and was imprisoned for three years.

Krzysztof Penderecki: Polish Requiem “Agnus Dei” (Warsaw Philharmonic Choir; Antoni Wit, cond.)

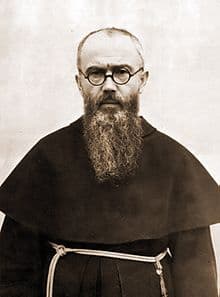

Father Maximilian Kolbe, 1936

One year later, Penderecki composed the “Recordare, Jesu pie,” written to mark the beatification of Father Maximilian Kolbe. Kolbe, a Polish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar was arrested by the Gestapo on 17 February 1941 and transferred to Auschwitz as a prisoner. At the end of July 1941, one prisoner escaped from the camp and the deputy camp commander picked ten men to be starved to death in an underground bunker to deter further escape attempts.

The Warsaw Uprising

When one of the selected men cried out, “My wife! My children!” Kolbe volunteered to take his place. The Dies Irae emerged in 1984 as a fortieth-anniversary remembrance of the Warsaw uprising against Nazi occupation. In 1944, the Polish underground resistance was fighting to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. The Uprising was fought for 63 days and eventually defeated by the Germans, who destroyed the city in retaliation. The work, as it stood thus far, received its first performance in Stuttgart on 28 September 1984, with Mstislav Rostropovich conducting.

Krzysztof Penderecki: Polish Requiem “Recordare, Jesu pie” (Stockholm Royal Philharmonic Choir; Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra; Krzysztof Penderecki, cond.)

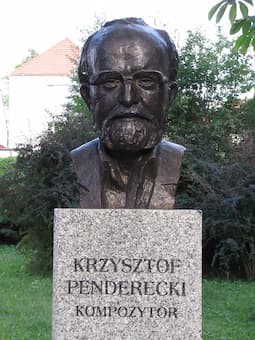

Statue of Penderecki

Nine years later, Penderecki added the “Sanctus,” and the complete work is scored for four soloists, large mixed chorus and an orchestra featuring quadruple wind and six horns. “It is among Penderecki’s largest works of 1980, and combined the Neo-Romanticism of his music from the late 1970s with more experimental procedures of his earlier years.” Stylistically it references music of the same genre written by other composers, ranging from Johann Ockeghem to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Giuseppe Verdi to Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky. As a scholar has noted, “alluding to so many, Penderecki does not identify himself with anyone, finding his own way and place in the history of the genre and producing a specific synthesis of tradition and modernity. He reaches out for a number of traditional elements, yet transforms them, builds a new hierarchy and subjugates grand dramatic forms of a monumental, theatrical character to his own, original concept.” We might call the work a dramatic oratorio, whose main subject is man’s attitude towards death. Penderecki summed up everything that preoccupied his country at a time of great crisis in “anticipation of life to come.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Krzysztof Penderecki: Polish Requiem “Dies Irae”