“My musical life started with hearing contemporary music”

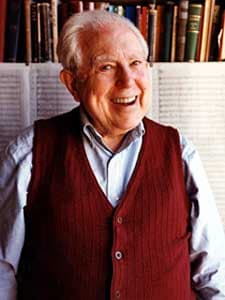

Elliott Carter

The American composer Elliott Carter (1908-2012) blended the “achievements of European modernism and American ultra-modernism into a unique style of surging rhythmic vitality, intense dramatic contrast, and innovative fracture.” Glowing accolades aside, Elliott Carter did hold a prominent place in modern music, with his compositions performed and recorded worldwide. In addition, he openly revealed his thoughts as a composer, critic, and teacher in a substantial number of written publications. He has served on numerous faculties, established music curricula, and written and spoken on the need to properly educate Americans, particularly new composers. Carter was born into a prosperous New York family, and he spent much of his childhood in Europe. In fact, he spoke French before he learned to read English.

The young Elliott Carter

Carter received very little musical encouragement at home, but started to develop an interest in modern music and explored modernism in literature, film, and theater. He was caught up in the avant-garde world of art in Greenwich Village and made friends with Charles Ives and the ultra-modernists Cowell, Varèse, Ruth Crawford, and, later, Nancarrow. Since Carter felt that he lacked the techniques to become a composer, he enrolled at Harvard as a music major. However, as he explained, “we had to write choral pieces in the style of Brahms or Mendelssohn, which was distressing because in the end, you realized how good Brahms is, and how bad you are.”

Elliott Carter: Tarantella (Andreas Grau, piano; Gotz Schumacher, piano; South West German Radio Vocal Ensemble; Marcus Creed, cond.)

Elliott Carter and Nadia Boulanger

Carter did complete his degree in 1932, having studied with Walter Piston, Edward Burlingame Hill, and Gustav Holst. Dissatisfied with his schooling, Carter continued his musical studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, first privately and later at the École Normale de Musique. He devoted himself to the study of strict counterpoint and basic techniques of Western musical composition. “Carter later destroyed all of his compositions written during his Parisian years and many pieces created in the 1930s.” Once he returned to the United States he was struggling to find employment during the Great Depression, and launched a career as a part-time music reviewer and critic in New York City. During this period Carter devoted himself mainly to writing short choral compositions, but he also crafted the ballets Pocahontas and The Minotaur. His Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, composed in 1948 is often considered a turning point in his career. Carter remembers, “When I was asked to write a work for the American cellist Bernard Greenhouse, I immediately began to consider the relation of the cello and piano and came to the conclusion that since there were such great differences in expression and sound between them, there was no point in concealing these as had usually be done in works of the sort. Rather it could be meaningful to make these very differences on the points of the piece.”

Elliott Carter: Sonata for Cello and Piano

Elliott Carter and Stravinsky

As Greenhouse later wrote, “the Cello Sonata is far above the common run of contemporary premieres; it is a happy confirmation of the quality of all of Carter’s recent work and a happier augury for the future.” For many critics, the Cello Sonata was Carter’s breakthrough work as it addresses an issue Carter had recognized earlier. As he wrote, “the first thing that struck me about contemporary music, in general, is that there was not much interest in rhythm.” To address this issue, his cello and piano parts often perform rhythmically independently, “not only in the metric placements of rhythmic patterns but also in implied tempo and rhythmic style.” Carter pursued his new compositional technique, subsequently termed “metric modulation” in a series of studies that display basic conflicts. “Between experimental innovation and technical discipline, between a politically inspired desire for simplicity and a deep-seated need for the complexity of expression.” It took many years for Carter to develop a musical language capable of serving his expressive intentions, “with the mature idiom only emerging fully in the First String Quartet of 1951.”

Elliott Carter: String Quartet No. 1

Oliver Knussen leads Elliott Carter on stage, 2008 © Hilary Scott

Under the influence of the European avant-garde, Carter “abandoned the long phrases and cumulative textures of the First Quartet and pursued a more fragmented, unpredictable, and dissonant style which nonetheless retains many elements of American ultra-modernism.” Yet, his use of rhythm continued to underscore the concept of stratification, with each instrument voice assigned its own set of tempos. Carter once explained, “that steady pulses reminded him of soldiers marching or horses trotting, sounds no longer heard in the late 20th century, and that he wanted his music to capture the sort of continuous acceleration or deceleration experienced in an automobile or an airplane.” Carter held teaching posts at the Peabody Conservatory (1946–1948), Columbia University, Queens College, New York (1955–56), Yale University (1960–62), Cornell University (from 1967) and the Juilliard School (from 1972). Elliott Carter wrote music every morning until his death of natural causes, on 5 November 2012 at his home in New York City, at age 103. Essentially, “Carter remained a loner on the American musical scene, affiliated with no group or school and indifferent to the changing demands of fashion and the marketplace. He once commented that the most radical work an American composer could write would be one like Brahms’s Fourth Symphony, which assumed the most highly developed musical culture in its listeners.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Elliott Carter: Dialogues II