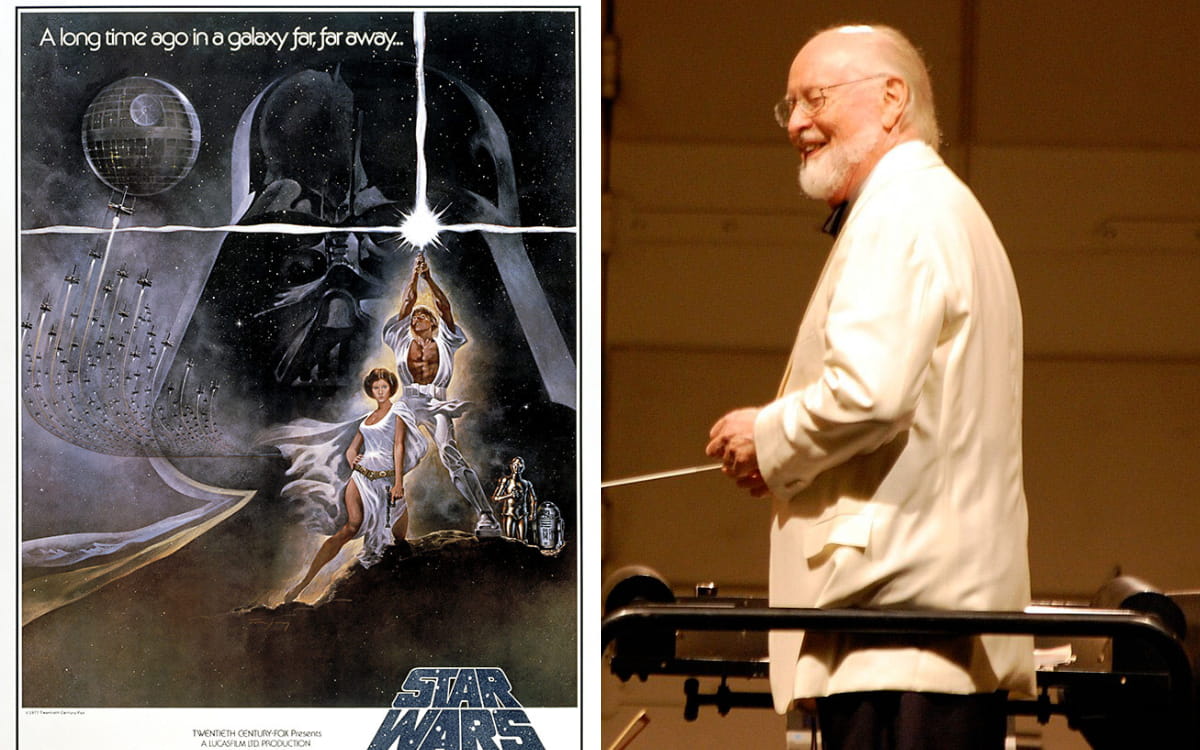

Do you know the answer to the question as to which film score the American Film Institute considers the greatest film score of all time? I am sure you can hazard a pretty good guess, but just in case, the correct answer is “Star Wars” of 1977. It revolutionized the movie industry by inundating the audience with spectacular visual and aural effects. It became an instant blockbuster hit, and quickly thereafter, a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. Critical to the phenomenal success of this film is the brilliant score by John Williams. Director Georg Lucas hired Williams on the recommendation of Steven Spielberg, after winning an Academy Award for the film Jaws.

John Williams: Star Wars, “Main Theme: A New Hope”

Originally, Williams was only hired to consult on the music editing choices and to compose the source music for the film. Lucas assembled his favorite orchestral pieces for the soundtrack, but eventually, Williams convinced Lucas that an original score would be unique and more unified. For his original score, Williams returned to a system of leitmotifs and composed a series of musical themes that represent the various characters, objects, and events in the film. The original film was part of a Star Wars trilogy, later augmented by a prequel trilogy, and finally a sequel trilogy. John William wrote the music for the entire franchise, “consisting of a total of over 18 hours of music.” He has written about sixty or seventy themes, “in one of the largest, richest collections of themes in the history of film music.”

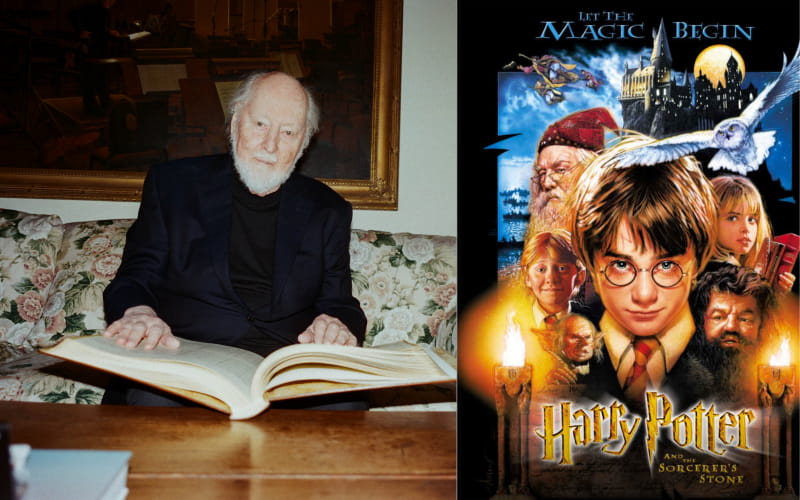

John Williams: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

You might have noticed that I have a somewhat unusual first name, but of course, there is an easy explanation. You see, the first installment of the Harry Potter series of eight fantasy novels written by J.K. Rowling was adapted and released as a fantasy film under the title “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” in 2001. As it turns out, it became the favorite film of my parents. A highly intelligent and overachieving character named Hermione Granger takes the female lead in this, and the other films of the series. She is described as “the brightest witch of her age,” and a “very strong female character.” I should say that I have a very strong female character indeed, but I am not so sure about being a witch. In the event, the name stuck. John Williams also composed the musical score for the first three “Harry Potter” films, and several of these themes and motifs were incorporated into later scores as well. Williams had started to compose for television in the 1950s and shifted to the big screen in the 1960s, writing a series of scores for disaster films. He quickly established himself as Hollywood’s foremost composer with three blockbusters, Star Wars, Close Encounters, and Superman. He also scored the Indiana Jones trilogy, and E. T. The Extraterrestrial. Williams has maintained a steady output of quality film scores up to the present time. Among his best-known works in recent years are Schindler’s List, Jurassic Park, The Phantom Menace, and of course, Harry Potter.

John Williams: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (Excerpts) (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; John Williams, cond.)

James Horner: Titanic

When it comes to some of my favorite films, and to the integration of choral and electronic elements into symphonic film scores, I immediately think of the American composer, conductor, and orchestrator James Horner. He graduated from the music schools of the University of Southern California and UCLA, and he wrote the music for some of the best-known films of our time. This includes Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Aliens, Field of Dreams, The Rocketeer, Braveheart, Deep Impact, A Beautiful Mind, Apollo 13, The Amazing Spider-Man, and many others. But, I haven’t even told you about his most successful scores. Horner wrote the music for the highest-grossing film of all time, James Cameron’s Avatar, and his score for Titanic became the best-selling orchestral film soundtrack of all time. Initially, James Cameron had his heart set on music composed by the Irish new-age musician Enya, but she declined. As such, Cameron chose James Horner to compose the film score. They had previously collaborated on Aliens, but the working relationship had been somewhat tumultuous. They disagreed on the song “My Heart Will Go On,” as Cameron did not want any songs with singing, and he worried about being criticized for “going commercial at the end of the movie.” In the event, Horner got his way and the Titanic collaboration proved highly successful.

James Horner: Titanic (Sissel Kyrkjebø, soprano; Celine Dion, vocals; King’s College Choir, Cambridge; Tony Hinnigan, flute/uilleann pipes; Eric Rigler, uilleann pipes; Eileen Ivers, violin; Ian Underwood, synthesizer; James Horner, piano; Tommy Hayes, bodhran; London Symphony Orchestra; James Horner, cond.)

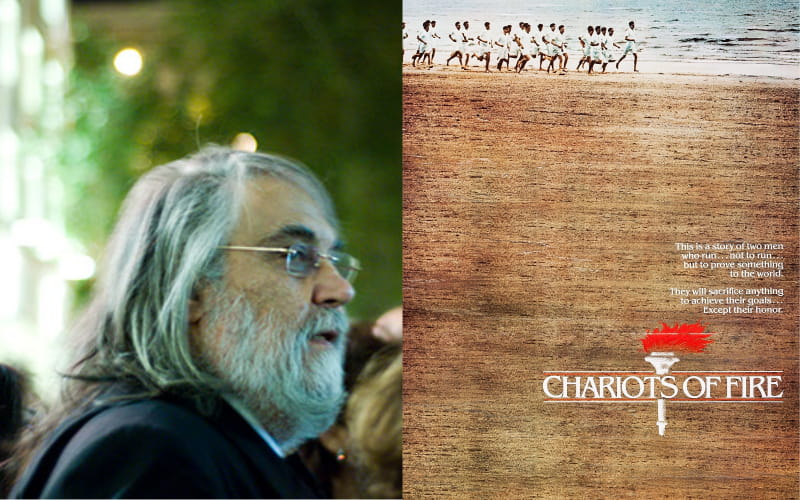

Vangelis: Chariots of Fire, “Main Theme”

The synthesizer started to have a major impact on film music during the 1980s. Capable of generating electronic audio signals, it “became an enormous aid to the composer, in part because of its ease in creating scores and parts. It also serves as a useful tool for the film director, who can now hear the general sound of the music before hiring a studio orchestra.” However, the synthesizer also became part of the modern studio orchestra, “where it not only imitates the sound of individual instruments, such as a harp, piano, or drums, but also gives support to the general sound of the strings. In some films, a synthesizer was substituted for an entire orchestra, as in the Oscar-winning score to Chariots of Fire. That score originated with the Greek musician, composer, songwriter, and producer Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou, better known as Vangelis. According to the composer, he “only accepted the scoring assignment for Chariots of Fire “because I liked the people I was working with. It was a very humble, low-budget film.” The music became a huge commercial success, and the opening sequence reached No. 1 on the US Billboard Hot 100 chart and sold one million copies in the United States alone.

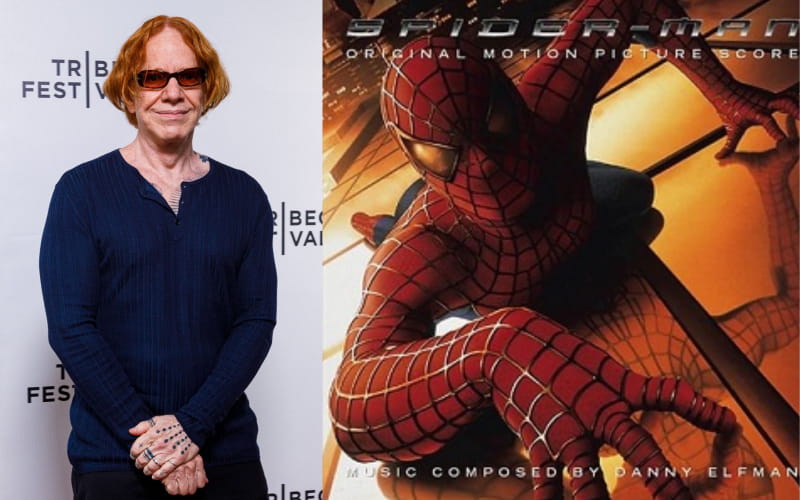

Danny Elfman: Spider Man, “Main Theme”

Modern audiences know Danny Elfman as the composer of the film scores for Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, Beetlejuice, Batman, Edward Scissorhands, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Men in Black, Fifty Shades of Grey, and the Spider Man series. In all, Elfman has composed music for over 100 feature films, as well as compositions for television, stage productions, and the concert hall. Significantly, Elfman belongs to the newest generation of film composers who lack traditional University training. He started his musical career as the singer-songwriter for the new wave band “Oingo Boingo” in the early 1980s. The band emerged from a surrealist musical theatre troupe, “The Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo,” known for their high-energy live concerts and experimental music. They performed a mix of rock, ska, pop, and world music over a period of 17 years. “Oingo Boingo” achieved significant popularity in Southern California, and Elfman was invited to write the score for his first feature film. As he explained, “Writing the melody is the easy part… But then, it’s what you do with it. That’s the skill, that’s the art, that’s what makes a great film score.” Elfman described the first time he heard his music played by a full orchestra “as one of the most thrilling experiences of his life.”

Danny Elfman: Spider-Man: Main title theme (arr. J. Wasson) (Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Robert Ziegler, cond.)

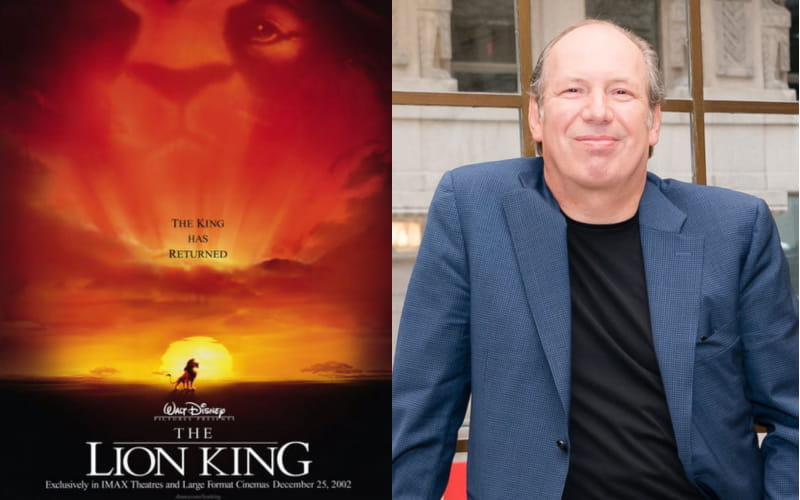

Hans Zimmer: Lion King

Like Danny Elfman, Hans Zimmer comes from a popular-music and synthesizer background. Growing up in Germany, Zimmer played the piano at home but he disliked the discipline of formal lessons. He once said, “my formal training was two weeks of piano lessons. I was thrown out of eight schools. But I joined a band. I am self-taught, but I’ve always heard music in my head. And I am a child of the 20th century, computers came in very handy.” Zimmer was inspired to turn his attention to film music when he heard the wonderful film scores of Ennio Morricone. In the event, so far, Zimmer has scored music for over 150 films and he continues to go strong. His breakthrough score to the 1988 film Rain Man was followed up with music for Driving Miss Daisy, and the soundtrack to Thelma & Louise directed by Ridley Scott. Scott explained, “I listen to Zimmer’s music and I don’t even have to shut my eyes. I can see the pictures. And that’s why, in many respects, I know I can talk pictures with Hans. He responds to pictures.” For the 1992 film The Power of One, Zimmer traveled to Africa in order to study African choirs and drums for the recording of the score. Two years later, he was hired to compose the score for the 1994 Disney Animation The Lion King. His score was adapted into a Broadway musical, which became the highest grossing Broadway show of all time.

Hans Zimmer: The Lion King: Lea Halalela (Keswa, vocals; Lebohang Morake, vocals)

Hans Zimmer: The Lion King: Busa (Keswa, vocals; Lisa Gerrard, vocals; Lebohang Morake, vocals)

Rachel Portman: Emma, The Cider House Rules, Chocolat and More

One of the most prominent female film composers in recent years is undoubtedly Rachel Portman. In fact, she was the first woman to win an Academy Award for Best music, for her original score from Emma. Born in Surrey and educated at Oxford, Portman started composing at the age of 14. Always interested in the relationship between music and film, she started to write music for student films and theatre productions. Her career took off when she began writing music for drama in BBC and Channel 4 films, and Portman has never looked back. She has since written over 100 scores for film, television, and theatre. She composed music for the Joy Luck Club, and received an Oscar nomination for her score to The Cider House Rules in 1999 and Chocolat in 2000. According to critics, “Portman is not just writing theme music that you can kind of pour all over a music; she writes character music.” Portman has written music away from the screen before, including an opera, a musical and an oratorio for children’s choir in response to climate change. In 2020, Portman stepped away from the screen once again, and her collection of intimate pieces for violin, cello, and piano titled “Ask The River” connects with the environmental issues of our time.

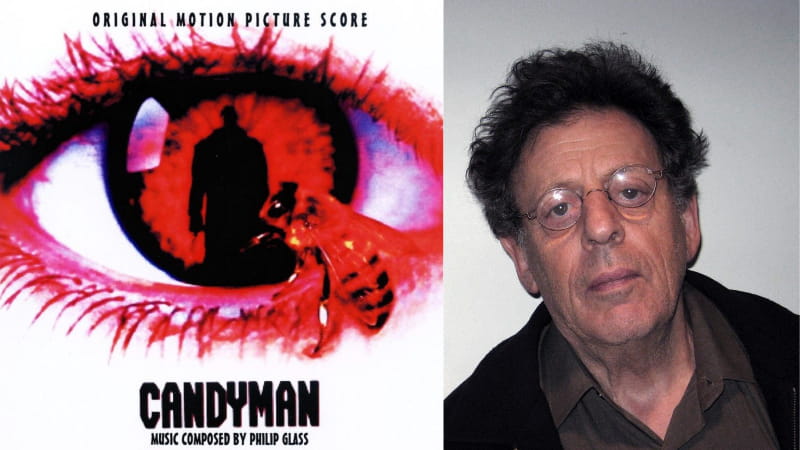

Philip Glass: Candyman, “Main Title Sequence”

American composers of art music once again turned to the medium of film during the 1990s. Among them was Philip Glass, who was called upon to compose the musical score for the 1992 gothic supernatural horror film Candyman. The story is based on the short story “The Forbidden” by acclaimed horror/fantasy author Clive Barker. Director Bernard Rose follows a Chicago graduate student completing a thesis on urban legends and folklore. She learns of the Candyman, a spirit who kills anyone who says his name five times in front of a mirror. Although skeptical, together with a friend she repeats the Candyman’s name before a mirror, but nothing happens. Things quickly turn grizzly, as the Candyman turns out to be the ghost of an African-American artist and son of a slave who was murdered in the late 19th century for his relationship with the daughter of a wealthy white man. Unlike most horror films Candyman is low on special effects but still delivers hair-raising suspense and surprising shocks, primarily with its creative imagery. Written for piano, pipe organ and chorus, Philip Glass’ score is perfectly suited for this modern gothic tale. Using some of his well-established techniques of rhythmic intensity and switching between major and minor key harmonies, “Glass’ score is as trance inducing and terrifyingly seductive as Candyman himself.” In the event, Glass was clearly pleased as he writes, “It has become a classic so I still make money from that score, get checks every year.” The score in minimalistic style has had much popular appeal, and Glass followed up with music for The Truman Show.

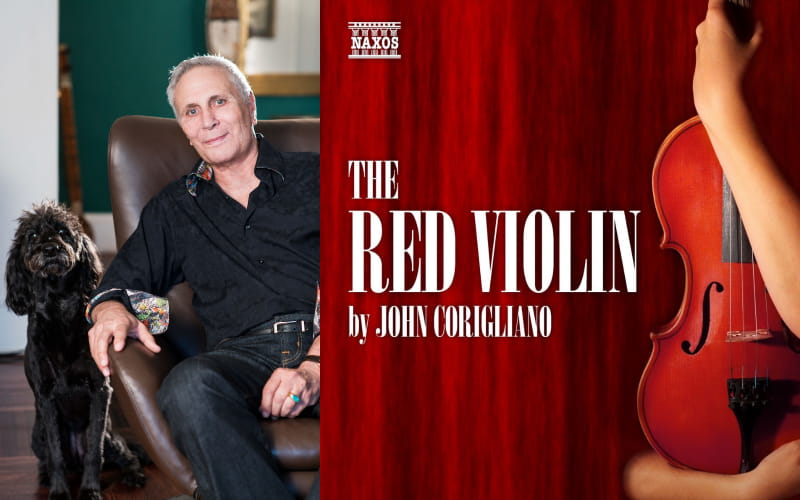

John Corigliano: Violin Concerto, “The Red Violin”

A leading figure in the music of the New Romanticism, John Corigliano received an Oscar for his haunting music to the film The Red Violin played by solo violinist Joshua Bell. The score is an overarching theme and variations that incorporates Baroque, Romantic, Chinese, and modern musical styles. Corigliano explains, “This score gave me an opportunity to visit my own past, for my father, John Corigliano was a great solo violinist and the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic for more than a quarter of a century. My childhood years were punctuated by snatches of the great concertos being practiced by my father, as well as scales and technical exercises he used to keep in shape. Every year, he played a concerto with the Philharmonic, and I vividly remember the solo preparation, violin and piano rehearsals, orchestral rehearsals and the final tension-filled concerts.” The scoring of the film inspired Corigliano to compose his Violin Concerto, “The Red Violin,” which is dedicated to the memory of his father. According to the composer, the story of “The Red Violin is perfect for a lover of the repertoire and the instrument. It spans three centuries in the life of a magnificent but haunted violin in its travels through time and space.”

John Corigliano: Violin Concerto, “The Red Violin” (Michael Ludwig, violin; Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Tan Dun: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Like Corigliano, Tan Dun is both a critically recognized composer of art music and a winner of an Academy Award for Best Music, Original Score for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. The music of Tan Dun is a “fascinating post-modern blend of Asian musical traditions and Western styles, including both avant-garde and popular.” He was born in Hunan Province in China and grew up during the Cultural Revolution. Once governmental restrictions were loosened, Tan Dun became a leading figure in the New Wave of Chinese composers who began to explore aspects of modern Western music. In 1983 the Chinese government, referring to his music as “spiritual pollution,” banned public performances of his works. He came to the US in 1986 and continued his musical studies at Columbia. The film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is a martial arts fantasy with stunning visual effects, that involves the story of two sets of doomed lovers. The soundtrack features Yo-Yo Ma throughout, and he is often heard in combination with Chinese instruments. Much of the melodic material is directly influenced by the vocal style of Beijing Opera. “Tan Dun draws upon Western harmony, Western popular-music rhythms, avant-garde timbres, and ethnic Chinese sounds,” and the song “A love before Time” was nominated for an Oscar for Best Song in 2000. To write on the Greatest Composers of Film Music was a wonderful assignment, and I am not sure that I was able to mention them all; which ones did I miss?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Tan Dun: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Yo-Yo Ma, cello; David Cossin, percussion; Shanghai Symphony Orchestra; Shanghai National Orchestra; Chen Xie-yang, cond.; Tan Dun, cond.)