Fanfares are a way of stating the obvious: a short ceremonial tune or a flourish on trumpets or brass instruments to introduce something or someone important. What happens when the fanfare becomes something else?

Tobias Picker: Old and Lost Rivers

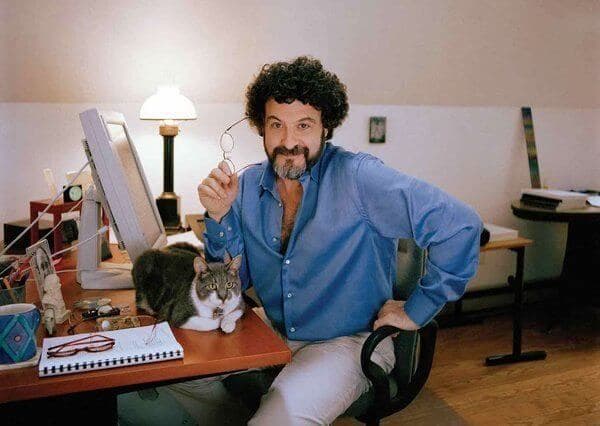

Tobias Picker (Photo by Harry Heleotis)

In 1986, as part of their sesqui-centenary celebrations, The House Symphony commissioned fanfares from contemporary composers. Tobias Picker, their Composer in Residence at the time, had commissioned ‘20 composers from Adams to Wuorinen to write short concert openers for each concert in our subscription season.’ Unfortunately, these 20 fanfares have been difficult to trace, but here are two that will give you an idea of what Tobias Picker had in mind.

Tobias Picker (b. 1954) contributed Old and Lost Rivers to the Project. He describes the scene: ‘Driving east from Houston along Interstate 10, you will come to a high bridge which crosses many winding bayous. These bayous were left behind by the great wanderings, over time, of the Trinity River across the land. When it rains, the bayous fill with water and begin to flow. At other times—when it is dry—they evaporate and turn green in the sun. The two main bayous are called ‘Old River’ and ‘Lost River’. Where they converge, a sign on the side of the highway reads: ‘Old and Lost Rivers’.’

Tobias Picker: Old and Lost Rivers (Houston Symphony; Christoph Eschenbach, cond.)

As you can hear, this isn’t a fanfare in what we might call a traditional sense – it’s soft, it’s moody, but in its intended position as the opener for a concert, it fulfilled its promise.

John Adams: Tromba lontana

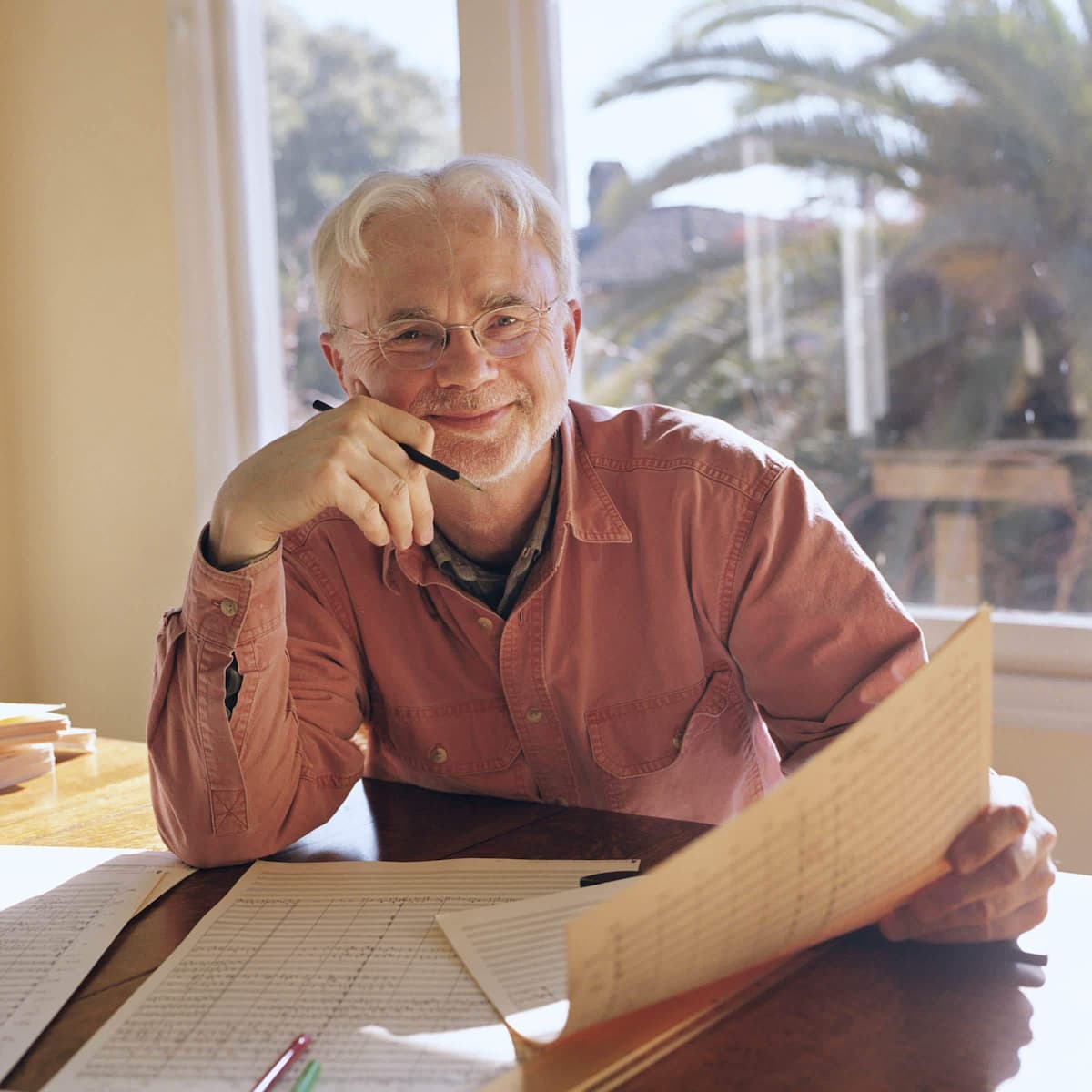

John Adams

Another composer in the project, John Adams (b. 1947), used trumpets, but with a very different effect.

Tromba Lontana was Adams’ contribution to the Project. He said: ‘Taking a subversive point of view on the idea of the generic loud, extrovert archetype of the fanfare, I composed a four-minute work that barely rises about mezzo piano and that features two stereophonically placed solo trumpets (to the back of the stage or on separate balconies), who intone gently insistent calls, each marked by a sustained note followed by a soft staccato tattoo. The orchestra provides a pulsing continuum of serene ticking in the pianos, harps, and percussion. In the furthest background is a long, almost disembodied melody for strings that passes by almost unnoticed like nocturnal clouds.’ The title translates as ‘distant trumpet’ and so it seems, present and yet backgrounded.

John Adams: Tromba lontana (Glenn Fischthal, Laurie McGraw, trumpets; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Edo de Waart, cond.)

Aaron Copland: Fanfare for the Common Man

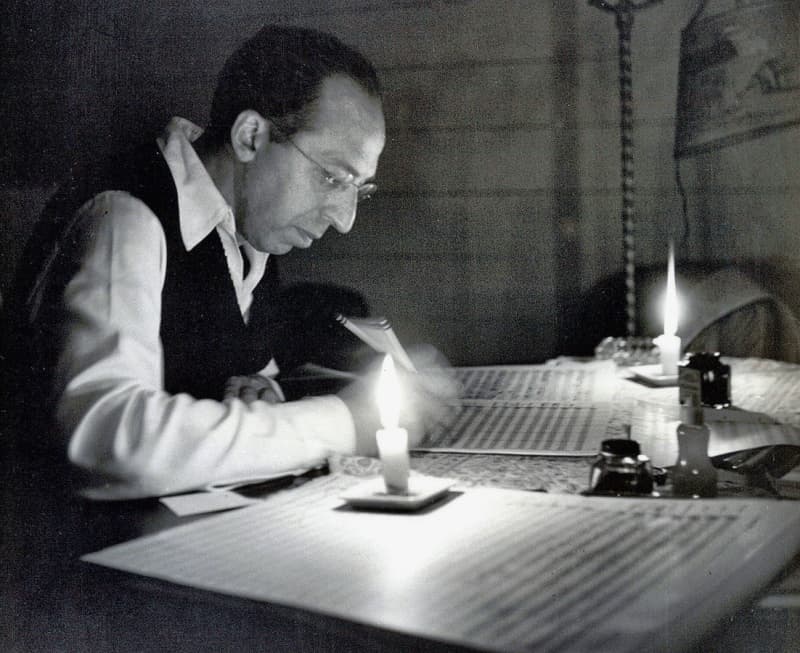

Aaron Copland in his studio in the Berkshires, 1946 (Photo by Victor Kraft)

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra’s own fanfare project bookends the Houston project. In the 1940s, the CSO commissioned and gave the premieres of 18 fanfares ‘in support of the Allied troops in World War II.’ The most famous out of that set of 18 was, of course, Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man, given its premiere in 1943.

Aaron Copland: Fanfare for the Common Man (Philadelphia Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

During the pandemic, the CSO commissioned new fanfares. But, as this was a time of lockdown and no public performances, these were works to be played by solo musicians of the CSO and recorded at home.

Again, we have to rethink the idea of fanfare. A fanfare is a music for an entrance. But what if you can’t go anywhere?

Courtney Bryan: Fanfare for Moments of Courage

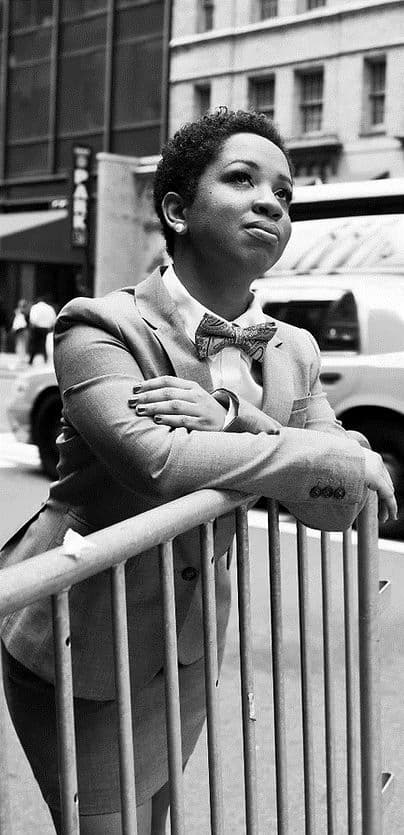

Courtney Bryan

New Orleans composer Courtney Bryan wrote her Fanfare for Moments of Courage, for CSO clarinetist Ixi Chen.

Rhiannon Giddens: Viola Fanfare

Rhaiannon Giddens

North Carolina native Rhiannon Giddens wrote her fanfare for violist and CSO/CCM Diversity Fellow Edna Pierce.

Daníel Bjarnason: Same Yet Different

Daníel Bjarnason (Photo: Börkur Sigþórsson)

Older genres could be explored, such as music for prepared piano, first created by John Cage in 1948. Here, Icelandic composer and conductor Daníel Bjarnason functions as both composer and performer in his work Same Yet Different. He views the prepared piano as an instrument that is a piano and, at the same time, isn’t a piano. ‘It becomes a thing of its own, borrowing properties from other instruments, mimicking them, but never becoming them.’ He relates this to looking forward to what would become ‘the new normal,’ i.e., normal but not the normal you knew before.

Du Yun: The Rest is Our World

Du Yun (Photo by Xiao Nan)

Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Du Yun used the recognition of First Responders that occurred in New York every evening at 7 pm when everyone opened their windows of isolation to make 5 minutes of noise banging pots and pans. One Saturday evening, after the pan-banging, someone played Sinatra’s New York, New York – even at a distance, the work affects all those who could hear it. Her work, The Rest is Our World, is played by principal harp Gillian Benet Sella with additional vocals by Mischa Sella.

Jonathan Bailey Holland: Trouble

Jonathan Bailey Holland

A fanfare that shows off the virtuosity of the trombone is Jonathan Bailey Holland’s Trouble, performed by Principal Trombone Cristian Ganicenco.

The fanfare is being redefined again – there’s no ceremony, there’s no ensemble, and, for all practical purposes, there’s no audience. These contributions to the fanfare as a concept, if not only as a genre, finally start to bring in the rest of the world—we have composers from all over the world of composition: young and old, men and women, with classical, folk and jazz background. To date, 20 composers have participated. Take a look at the Fanfare Project to see the range of works that have been recorded.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter