How private was Maurice Ravel’s private life? Well, to this day nobody has uncovered conclusive evidence that he ever had a sexual relationship. While his music is passionate and distinctive, Ravel’s personality remains mysterious. His friend and biographer Alexis Roland-Manuel wrote, “He is intelligent, open, and natural in everything he says. He judges himself and others with a strong desire for impartiality and a clear-sightedness which is quite rare in an artist.”

Maurice Ravel with Marguerite Long

Even though Ravel was a private and secret person, he did enjoy the company of others and was faithful in his friendships to a rare degree. He used to say; “One does not prove he has a heart by simply opening up his chest.” And one of his dearest and closest friends, the exceptional pianist Marguerite Long (1874-1966) famously wrote, “Maurice Ravel is reserved, sacred, and distant with unwelcome visitors, he was the surest, most delicate, and most faithful of friends. By his exterior appearance, his witticisms, and his love of paradoxes, he has often contributed to crediting the myth of spiritual indifference, but, in spite of these appearances, this great prisoner of perfection hid a sensitive and passionate soul.”

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto in G Major

The French poet, musician, painter, and art critic Léon Leclère (1874-1966) was primarily known under the pseudonym Tristan Klingsor. He steadfastly maintained that he combined the names of Wagner’s hero Tristan and his villain Klingsor—from Parsifal—because “he liked the sounds they made.”

Tristan Klingsor (Léon Leclère)

Together with Ravel, Klingsor belonged to the Paris avant-garde artistic group known as “Les Apaches” whose meetings he sometimes hosted. That association—we are still uncertain as to how close the relationship really was—bore immediate fruit when Ravel set three poems from the poet’s anthology Shéhérazade. Ravel selected poems ranging from the colorful depiction of various Asian locals, to musically encoding a harem-like atmosphere and a “languid seductiveness.” Klingsor had warned his readers to think of the poet not as a turbaned Oriental caught up in an opium-induced dream, “but rather as one who cultivates a sensitive reaction to his surroundings.” According to Klingsor, “Ravel adored puerile fantasy worlds, and he perfectly emulated the style and rhythm of the vocal lines.”

Maurice Ravel: Shéhérazade (Frederica von Stade, mezzo-soprano; Boston Symphony Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Group photo of “Les Apaches”

As part of a group of innovative young artists, poets, critics, and musicians, Maurice Ravel joined “Les Apaches” (The Hooligans) around 1900. That name was coined by Ricardo Viñes to represent their status as “artistic outcasts.” They met regularly until the beginning of the First World War, and members stimulated one other with intellectual arguments and performances of their works. The membership of the group was fluid, and at various times included Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla as well as their French friends. Among the enthusiasm of the Apaches was the music of Claude Debussy.

Nadar: Claude Debussy (1908)

Ravel, twelve years his junior, had known Debussy slightly since the 1890s, and their friendship, though never close, continued for more than ten years. The two composers ceased to be on friendly terms in the middle of the 1900s, with Ravel writing, “Debussy’s genius was obviously one of great individuality, creating its own laws, constantly in evolution, expressing itself freely, yet always faithful to French tradition. For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy . . . I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of his symbolism.” But it was public tension—as admirers began to form factions adhering to one composer or the other—that led to personal estrangement.

Maurice Ravel: String Quartet in F Major (Melos Quartet)

According to Alexis Roland-Manuel (1891-1966) “Maurice Ravel as artist and man have always intrigued the critics because he slides from their grasp, eludes the intellectual analyst as he does the writer of romantic biographies.” Roland-Manuel initially studied violin with Albert Roussel at the Schola Cantorum, but on the advice from Erik Satie became a student of Maurice Ravel. He became a devoted follower of the composer, and while he wanted to jealously guard their relationship, he also used his knowledge of the composer to establish Ravel as a subject of scholarship.

Ravel with Alexis Roland-Manuel

Roland-Manuel was certainly close to Ravel, but he remained more of a disciple and student than a peer. In fact, he took the role of scribe for Ravel in his publications and commentary on Ravel’s “Autobiographical Sketch,” reserving his own revised perspective for his 1938 biography. “It is not necessary to know Ravel personally,” he writes, “or to have delved deeply into his thoughts to be convinced that the methods of this musician, his technique, and his art in its entirety suggest deliberate research and mistrust of inspirations.”

Maurice Ravel: Boléro (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

The Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes (1875-1943) arrived in Paris with his mother in 1887. He first met Ravel at the private piano studio Cours Schaller, and both entered the Conservatoire taking lessons with Bériot. Viñes became Ravel’s best friend during adolescence and early maturity, and he was the first interpreter of his piano music while serving as an important link between Ravel and Spanish music. His observations provide a vital portrait of the composer lasting from the late 1880s to the 1914-18 War.

Ricardo Viñes

In his private diary, Viñes writes on 1 November 1896. “They had played the Prelude de Tristan and… Ravel, the super-eccentric decadent was shaking convulsively and was crying like a child, but deeply, because spasmodically, tears slipped out of him. Until now, despite the high opinion I had about Maurice Ravel’s intellectuality, as he is so uncommunicative for the most little things of his life, I believed that, perhaps, there was a bit of bias on his part and of elegance in his opinions and literary taste; but since this afternoon, I see that this man is born with inclinations, likings, and opinions and that, when he expresses them it is not to look snobbish or to follow fashion, but because he really feels them and I take advantage of this occasion to declare that Ravel is a most ill-fated and unrecognized being because he’s taken for a failure whereas he’s in fact an intelligence and a superior artist who would deserve a wondrous destiny. He is, moreover, very complex; there is in him a mixture of medieval catholic and satanic ungodly, but with also the love towards Art and Beauty that guides him and makes him feel ingenuous, as he proved today, crying at the hearing of the Prélude de Tristan.”

Maurice Ravel: Jeux d’eaux

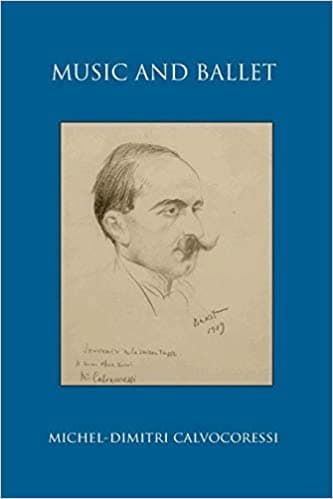

Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi (1877-1944) was a critic and musicologist of Greek parentage, French birth, and English adoption. Ravel met him while studying at the Paris Conservatoire, and they both shared an interest in exotic musical influences. Both were part of “Les Apaches,” and strongly believed that native folk songs were an important source of artistic inspiration.

Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi

Calvocoressi was working with a group of musicians and musicologists at the École des Hautes Études-Sociales in Paris. The musicologist Pierre Aubry needed to illustrate a lecture he was giving on Greek folksong. He asked Calvocoressi to select some Greek songs for illustrative purposes. Calvocoressi made his selection from a collection compiled by Hubert Pernot, a linguist and professor of Modern Greek at the Sorbonne, and then taught the songs phonetically to the singer Louise Thomasset. She was happy to perform them on short notice but was looking to have a suitable piano accompaniment. As such, Calvocoressi asked Ravel to write an accompaniment for these five melodies, and Ravel supplied them in thirty-six hours.

Calvocoressi was mightily impressed by this “extraordinary feat,” and asked Ravel to produce three more. The new collection, selected from a total of eight, was first performed (in Greek) in Paris and published in French translation in 1906. Ravel began the task of orchestrating them but soon lost interest, and it was left to his last student of consequence, Manuel Rosenthal, to complete the task in 1935.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: 5 Melodies Populaires Grecques (Victoria de los Angeles, soprano; Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; Georges Prêtre, cond.)

Sound is SUPERB in my Sony headphones! Listening now to the Ravel. Good performance!

Cool story:

Ravel once said that it was impossbile to effectively write for the piano anymore to his close circle of friends so in response Florent Schmitt wrote Les Lucioles (from his Nuits Romaines Op. 23) and this provoked Ravel to write Jeux d’Eau. He also wrote Ombres (shadows) which is very similar to Gaspard de la Nuit.