Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 has the reputation of being one of the most technically challenging piano concertos in the piano repertoire. It first sounded on 28 November 1909 in New York City with the composer as soloist and the New York Philharmonic Society conducted by Walter Darmrosch. The concert was attended by the largest audience the Philharmonic Society had had for a Sunday concert that season. According to a critic, “A mood of honesty and simplicity and the single pursuit of musical beauty, without the desire to baffle or astonish, dominated Mr. Rachmaninoff’s playing of his new concerto. The pianist’s touch had the loving quality that holds something of the creative and his execution was sufficiently facile to meet his self-imposed test.”

Rachmaninoff in 1909

When it came to the musical aspects of the concerto, reviews were complimentary but not uncritical. “The concerto was too long and it lacked rhythmic and harmonic contrast between the first movement and the rest of the concerto,” wrote a critic. “The new concerto, then, may be taken as a purely personal utterance of the composer and it has at times the character of an impromptu, so unstudied and informal in its speech and so prone, too, to repetition.” Following the performance, Rachmaninoff was recalled several times as the audience demanded an encore or two. Apparently, he held up his hands with a gesture that although he was willing, his fingers were not. “So the audience laughed and let him retire.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 “Allegro ma non tanto”

Rachmaninoff’s playing was once more the focus of attention at a repeat performance some days later. A critic writes, “The direct expression of the work, the extraordinary precision and exactitude of his playing, and even the strict economy of movement of arm and hands which M. Rachmaninoff exercises, all contributed to the impression of completeness of performance… It is regrettable that despite its many beauties, the work suffers from overlength. There is extra baggage in the first and last movements, which could be removed to the advantage of the work. Judicious curtailment would help the concerto to a deservedly long term of life. The work grows in impressiveness upon acquaintance and will doubtless take rank among the most interesting piano concertos of recent years, although its great length and extreme difficulties bar it from performances by any but pianists of exceptional technical powers.”

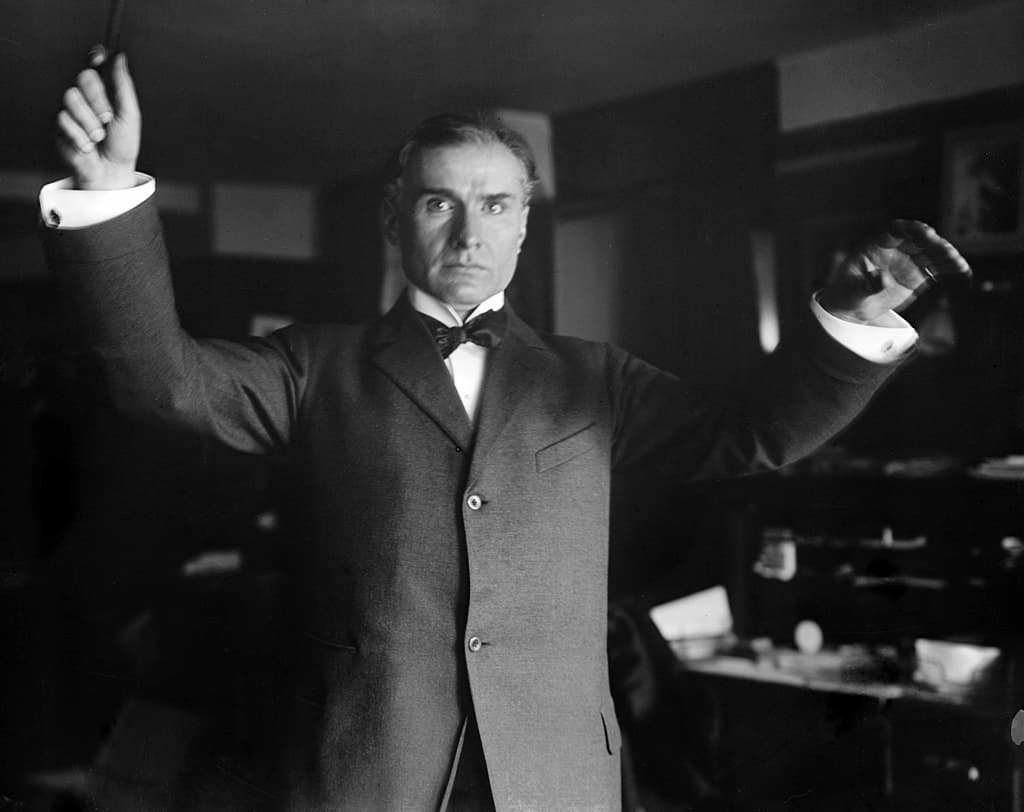

Walter Darmrosch

Critics were unanimous that the third concerto was not as striking in its originality as Rachmaninoff’s second, that in parts it was vague and groped for form and theme, and that it was so loosely put together that one was more interested in the statement than in its development. The work was composed in the summer of 1909 in almost complete mystery, and there is no record in either Rachmaninoff’s Recollections or in any of his letters, concerning his work on this piano concerto. In the event, Rachmaninoff also performed the work under Gustav Mahler on 16 January 1910. Rachmaninoff reports “Mahler was the only conductor whom I considered worthy to be classed with Nikisch. He devoted himself to the concerto until the accompaniment, which is rather complicated, had been practiced to perfection. Every detail of the score was important to him, an attitude too rare amongst conductors.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 30 – II. Intermezzo: Adagio (Sergei Rachmaninoff, piano; Philadelphia Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

Part of the music score of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3

In his Third Concerto, Rachmaninoff illustrates to perfection his considerable gift for writing long, beautifully phrased melodies, and uses his material intelligently to create three unified movements with a wide diversity of moods. But after spending three months in the United States, he was ready to go home. As he writes to a friend, “I am weary of America and I have had more than enough of it. Just imagine, concertizing almost every day during the three months! I have played my own compositions exclusively. I was a great success and I was recalled to give encores as many as seven times. This was a great deal, considering the audiences there. The audiences are remarkably cold, spoiled by the guest performances of first-class artists, those audiences, which always seek something extraordinary, something different from the last one. Their newspapers always remark on how many times the artist was recalled to take a bow and for the large public this is the yardstick of your talent if you please.”

Rachmaninoff proofing his 3rd Piano Concerto, 1910

Rachmaninoff was hoping to make his work more popular, and he authorized several cuts in the score, to be made at the performer’s discretion. These cuts, particularly in the second and third movements, were commonly taken in performances and recordings during the initial decades following the concerto’s publication. However, the Rach 3 really only started to gain serious traction once Vladimir Horowitz included it in his repertoire.

Vladimir Horowitz, 1928

Rachmaninoff was in the audience when Horowitz made his American debut at Carnegie Hall in 1928. Apparently, he told Horowitz “Your octaves are the fastest and loudest, but I must tell you, it was not musical.” Horowitz visited Rachmaninoff the next day and they played through the 3rd concerto, with Horowitz taking the solo part. With a twinkle in his eyes, Horowitz once noted, “Rachmaninoff could always find something to complain about in any performance.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (Horowitz)

Horowitz: warts and all, an extraordinary live occasion!