We now think that the Glass Harmonica is simply an instrument with an otherworldly tone, but at its heyday in the late 17th century, it was an instrument that some thought could drive you mad.

Musical Glasses, or glasses filled with water to varying depths, will resonate when the edges are rubbed with a wet finger. However, usually, only one note or two notes could be played at a time. Benjamin Franklin, after seeing a concert where musical glasses were played, invented what he called the Armonica, the name coming from the instrument’s harmonious sounds. Franklin turned the instrument on its side and automated the sound-producing process. He created glasses of varying sizes, connected them with a horizontal rod through their centres, and then rotated them. The player moistens his fingers in water and then touches the edges of the rotating glasses. The performer could play multiple glasses at once.

Musical Glasses

William Zeitler playing the glass harmonica

Franklin’s 1761 invention sparked a flurry of imitators: it’s estimated that in the next 70 years, some 4,000 instruments were built and some 400 works were composed for the instrument.

The instrument was not without controversy: while some viewed the sound as angelic (early versions of the musical glasses were called the ‘angelic organ’ or ‘seraphim’), others viewed it as so dangerous that ‘…the strongest man could not hear it for an hour without fainting.’ The glass harmonica was accused of causing nervous problems, domestic squabbles, premature deliveries, fatal disorders, and convulsions in animals. Some towns banned the instrument from being played at all. Anton Mesmer, known for his experiments with hypnosis (mesmerism) used the instrument in his treatments. The instrument was wrongly blamed for the death of Beethoven with the rumour that the lead in the glass accelerated his death.

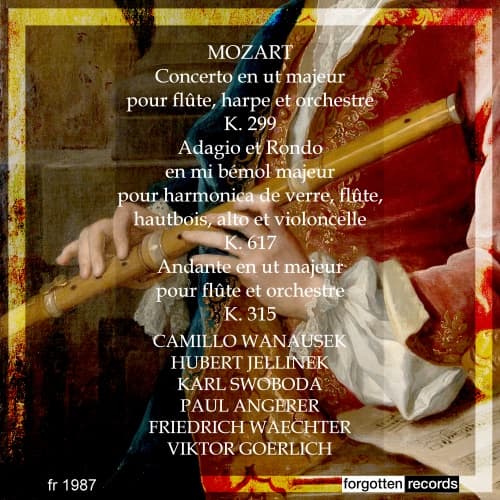

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart heard the instrument played by the blind virtuoso Marianne Davies (1740-1792) in London in 1784 and later he heard her again in Vienna. He loved the instrument and played it himself. His father, Leopold Mozart, was introduced to the instrument by Anton Mesmer, and, in a letter to his wife, told her how much he wanted one. In May 1791, Mozart composed the Adagio and Rondo, K. 617 for the blind performer Marianne Kirchgessner (1770-1808). It was the last chamber work Mozart wrote. He played in the work’s premiere on 19 August 1791, performing the viola part.

In modern days, when most glass harmonicas are in museums, the celeste, another instrument with an unearthly tone, was substituted for the older instrument.

The Adagio was praised for its unearthly beauty and the Rondo pushes the glass harmonica/celeste forward as soloist, often in dialogue with the flute, which had a complementary tone.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Adagio and Rondo for glass harmonica, flute, oboe, viola and cello, K. 617

Camillo Wanausek

This recording was made in 1954 in the Mozart-Salle at the Konzerthaus, Vienna, with the ensemble of Karl Swoboda, celeste; Camillo Wanausek, flute; Friedrich Waechter, oboe; Paul Angerer, viola; and Viktor Goerlich, cello, who were members of the Pro Musica Chamber Orchestra, Vienna.

Performed by

Camillo Wanausek

Karl Swoboda

Paul Angerer

Friedrich Waechter

Viktor Goerlich

Recorded in 1954

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter