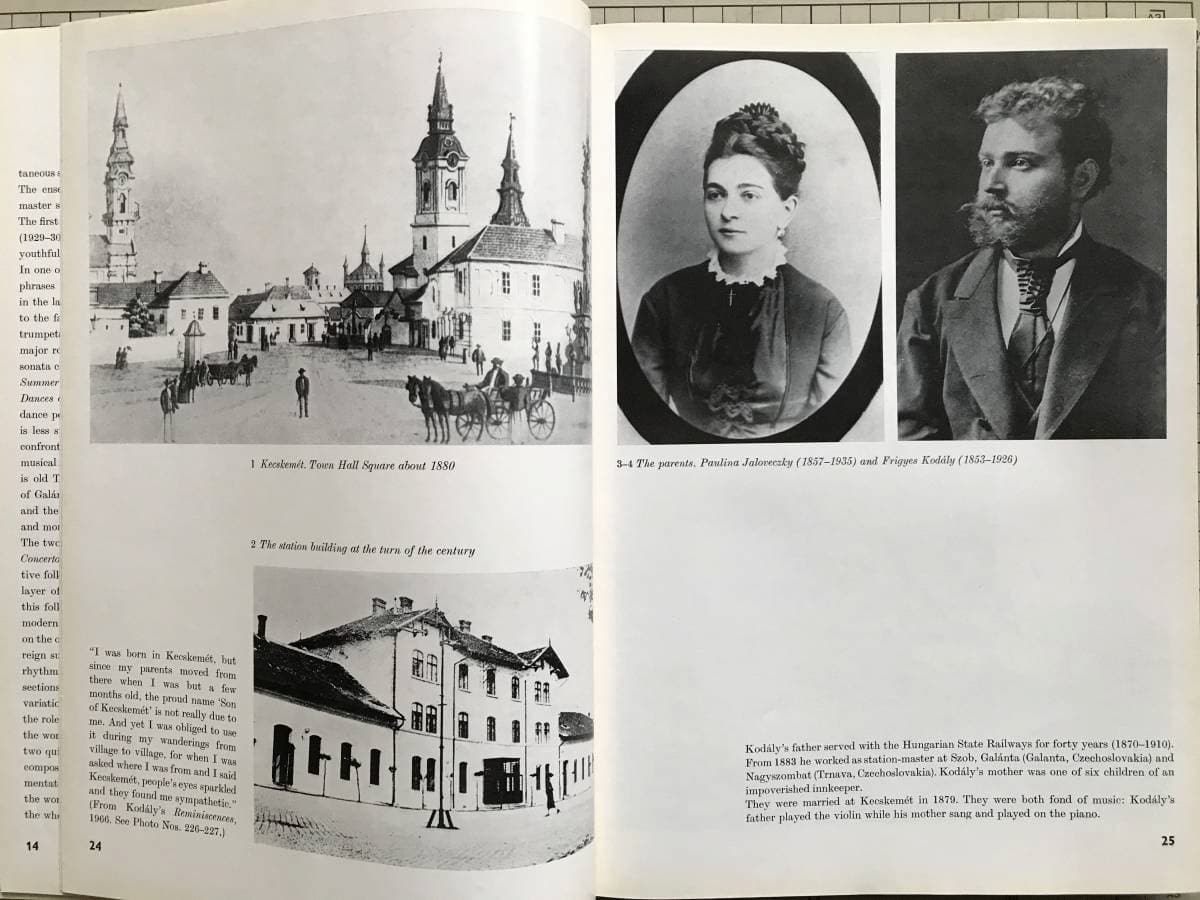

Zoltán Kodály was born in the Hungarian city of Kecskemét on 16 December 1882. His father worked for the railroad, having risen to the rank of stationmaster by 1883. He was described as “a plump, reticent man of medium height, who won the respect of his colleagues and superiors by his honesty and efficiency.” He married Paulina Jaloveczky in 1879, and the relationship produced three children. As a railroad official, the family was constantly on the move, and Zoltán spent, what he described as ”the best seven years of his childhood,” in the village of Galánta in western Hungary.

Zoltán Kodály, 1900

He attended primary school amongst an ethnically mixed group of pupils, and he would subsequently return to the region on his first expedition as a collector of folk songs. In fact, the region would become immortalized in his 1933 composition Dances of Galánta. Kodály’s first musical experiences were connected to the Galánta region, as his earliest composition, a short song for two voices titled Bicinia Hungarica dates from his primary school days.

Zoltán Kodály: Dances of Galánta

Zoltán grew up in a musical household, as his father was a good violinist. His mother was a competent pianist and informal chamber music gatherings were part of the household activities. The family moved to Nagyszombat, in the north-western part of Hungary in 1892. Currently named “Trnava” and located in western Slovakia, it was the seat of a Roman Catholic archbishopric, and the historic centre consists of a number of churches within its city walls. Known as the “Slovak Rome,” Kodály was fascinated by the historical associations and Latin inscriptions on the walls of houses and churches. He started to take piano lessons, but quickly took up the violin and was soon playing in the school orchestra.

The Kodály family moved to Trnava in 1892

Kodály taught himself to play the cello, sang in the choir at the cathedral, and began to study musical literature. He later recalled, “At the student service in the old church of the Invalids for a long time we sang nothing but German church music. At the Cathedral, where I used to go to High Mass on Sundays, the musical life was far more intense and many good instruments in the orchestra for which there were no players, and the tattered old scores were left lying about all over the place.”

Zoltán Kodály: Stabat mater (Pecs Bela Bartok Male Choir; Tamas Lakner, cond.)

Kodály vividly remembers, “In the stillness of the choir, I picked up a broken bassoon that had been left there, and wondered how you would produce music from such an instrument and how it might once have sounded. For me, that broken bassoon became a symbol of how, if musical culture was to be recreated in Hungary, one would have to build it with fragments of its past.” Kodály made his first public appearance as a composer, writing an overture for school orchestra that was performed in February 1898.

Birthplace and Parents of Zoltán Kodály

Thanks to an advert in the local paper, a critic was present and wrote, “the composition sounds well; there is a logical succession in the arrangement of the themes… The piece reveals a dynamic talent.” It was clear to everyone that Kodály possessed great musical promise, but his parents urged him to become a lawyer or a teacher. Heeding his parents’ wishes, he enrolled at the faculty of philosophy at the University of Budapest. He attended classes in accordance with his literary interest, and he took the entrance examination at the Royal Hungarian Academy of Music.

Zoltán Kodály: Romance lyrique (Ildikó Szabó, cello; Agota Lenart, piano)

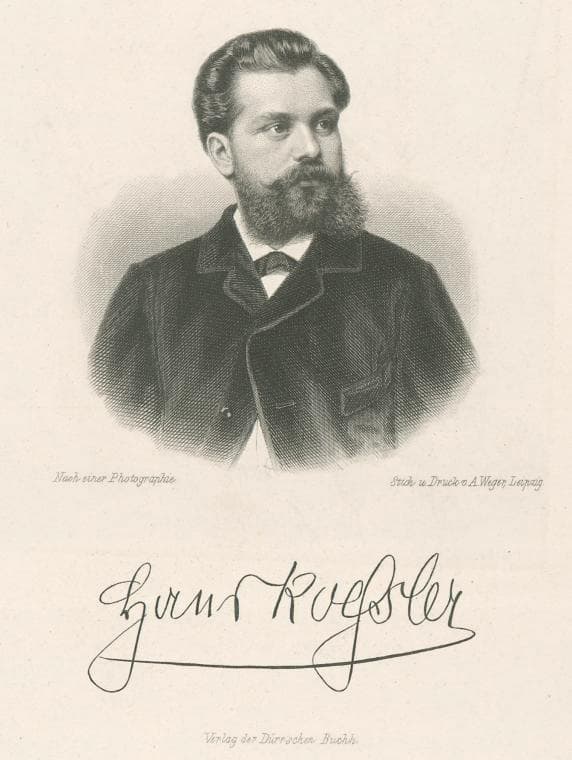

Kodály was quickly accepted into the composition class of Hans von Kössler, who also counted Dohnányi, Bartók, and Weiner among his students. Kodály passed his examination at the head of the class, and “had soon won a reputation for his outstanding grasp of counterpoint.” A biographer writes, “his end-of-term and examination composition reveal him as still a disciple of Haydn and the romantic composers, particularly of Schubert, yet at the same time it is clear that he was already, and increasingly consciously, beginning to draw on the Hungarian motifs which he believed should be dominant in Hungarian music.”

Hans von Kössler

Apparently, his line of thinking caused some friction as Kössler considered Hungarian motifs as “nothing more than ornamental materials.” After graduation, Kodály spent four years at Eötvös College, a training college for gifted teachers, and he perfected his knowledge of English, French, and Germany. In addition, he was introduced to research in the music of language. Kodály passed the examination for his teacher’s diploma in 1905, and in the same year, undertook his first expedition back to the countryside in search of folk songs.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Zoltán Kodály: String Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 2 (The Audubon Quartet)