Sometimes you get tired of the details, tired of the intricate formal structure, and you just long for a piece of simple music. This is where Light Music plays a role. Starting in the 18th century, light music was the contrast to absolute music. Here was music that was simple and that, as one writer put it, satisfied all the Ts: Tunes, Tonality, Triads, and the Tonic. No complicated excursions to far keys, but rather an emphasis on the melodies and the rhythms.

A work such as a movement from Richard Rodney Bennett’s The Aviary, gives us a key to the genre: simple, melodic, and engaging.

Richard Rodney Bennett: The Aviary – I. The Bird’s Lament (Royal Ballet Sinfonia; Gavin Sutherland, cond.)

Malcolm Arnold’s sets of English Dances, created at the invitation of his publisher who wanted a response to Antonín Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances. Jollity mixes with melancholy here, and at the same time, is capable of brash brass statements, as in No. 4 of the first set of English Dances. When the BBC used this as the theme for a radio program, people phoned in to find out about that intriguing piece they’d just heard.

Saffron Blaze: Castle Combe, Cotswold

Malcolm Arnold: English Dances, Set 1, Op. 27 – No. 4. Allegro risoluto (Philharmonia Orchestra; Bryden Thomson, cond.)

Folk dances figure largely in this genre, not only for their emphasis on melody and rhythm but also because they have a local familiarity, even when they’re new to the listener. Philip Lane’s Suite of Cotswold Dances, which takes its name from a second of central-southwest England, carries the designation of an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Philip Lane: Suite of Cotswold Folkdances – I. Wheatley Processional (Royal Ballet Sinfonia; Gavin Sutherland, cond.)

Many of the great British composers of Light Music had careers in the film and television business and so much of the familiarity we have with their music comes not from the concert stage but the glowing screens in our living rooms, such as the music of Geoffrey Burgon. The name may be unfamiliar, but the melodies aren’t. The music for the BBC series Brideshead Revisited is an excellent example of the evocation of an England of the past in a 1981 piece of music.

Brideshead Revisited , Jeremy Irons (Chales Ryder), Antony Andrews (Sebastian Flyte), and Diana Quick (Julia Flyte), 1981

Geoffrey Burgon: Brideshead Variations – Theme (Adelaide Symphony Orchestra; José Serebrier, cond.)

A similar theme was used for the Miss Marple films in the 1960s, and reused for the television series in 1985 with Joan Hickson. The composer, Ron Goodwin, is probably better known for his film scores for movies such as Where Eagles Dare, Force 10 from Navarone, Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, Of Human Bondage, and Hitchcock’s Frenzy.

Joan Hickson as Miss Marple

Ron Goodwin: Miss Marple’s Theme (Consort, John Altman, cond.)

Eric Coates made his name with his Knightsbridge march, but it was By the Sleepy Lagoon, written in 1930, that gave him long-lasting fame. This slow waltz for orchestra was discovered and lyrics were set to it (with the composer’s permission) it became a popular music hit for Glenn Miller, trumpeter Harry James, and singer Diana Shore. It also has been the theme for BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in 1942.

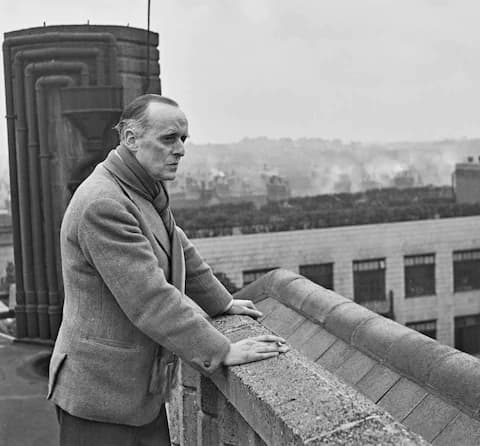

Eric Coates

Eric Coates: By the Sleepy Lagoon (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Andrew Penny, cond.)

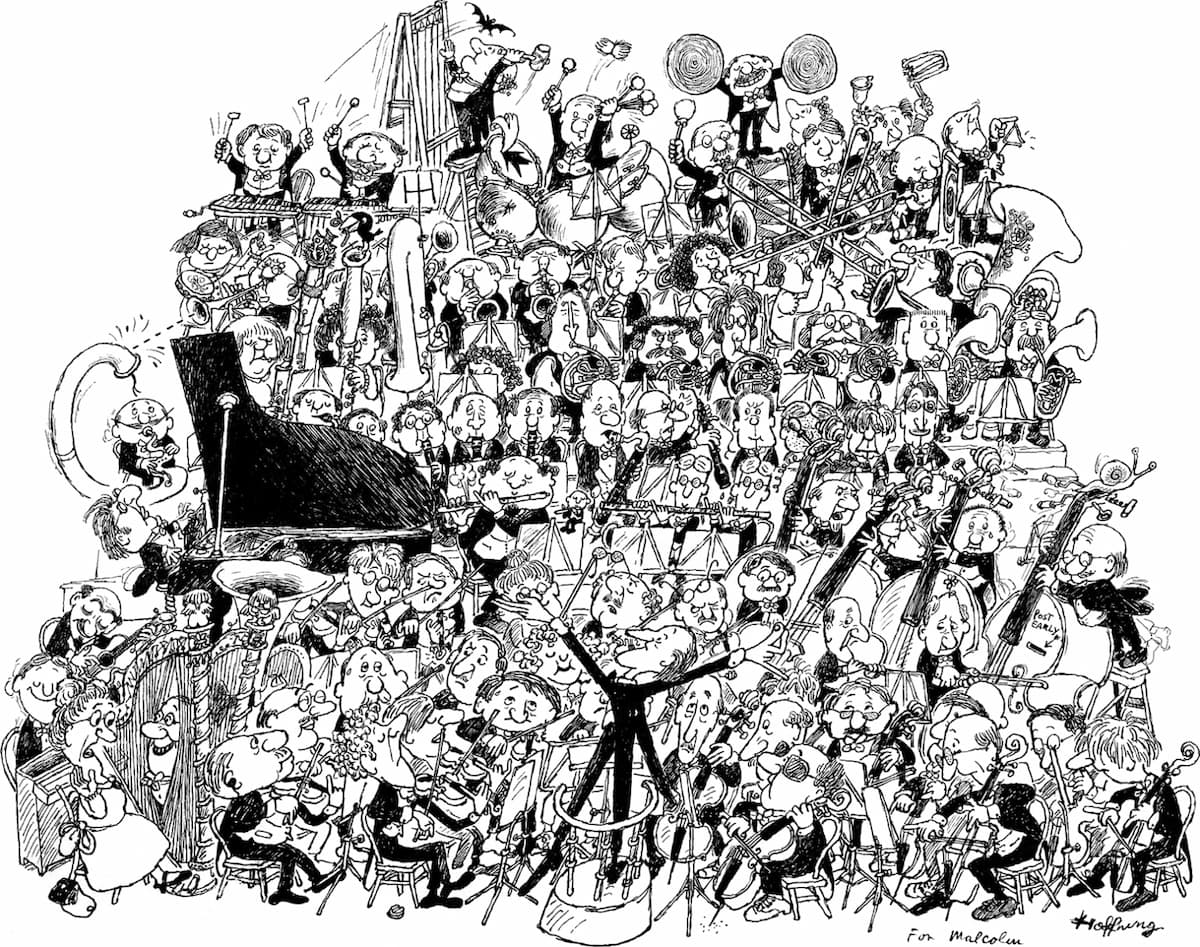

Another side of light music is humour. For the 1956 Hoffhung Music Festival, Malcolm Arnold wrote A Grand Grand Festival Overture, but the 4 soloists are not on the typical musical instruments but perform on 3 vacuum cleaners and a floor polisher.

Gerard Hoffnung: The Hoffnung Symphony Orchestra

Malcolm Arnold: A Grand, Grand Festival Overture

Gordon Jacob made free with the music of Rossini in his 1960 overture The Barber of Seville Goes to the Devil.

Gordon Jacob: The Barber of Seville Goes to the Devil – Overture (Royal Ballet Sinfonia; Gavin Sutherland, cond.)

The heyday of Light Music really happened in the mid-20th century. It was such a popular subgenre of classical music that the BBC even had an entire radio channel, the BBC Light Programme, for this music that ran from 1945 to 1967, whereupon it was replaced with BBC Radio 2 (older pop music) and BBC Radio 1 (current pop music). Ease of access seems to have fallen to the self-importance of modern music but it’s all still fun to listen to!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

I absolutely LOVE Malcolm Arnold’s music. This Overture seems trash, but who cares? It grows on you. What imagination!

Malcolm Arnold’s English Dances feels a little similar to Jupiter from Holst’s “The Planets”