Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908), alongside Henryk Wieniawski, Joseph Joachim, Eugène Ysaye, and countless others, was part of a group of violin virtuosi that decidedly contributed to the development of instrumental music as both performers and composers. But what is more, Sarasate’s distinctive technique and performance style inspired a number of masterworks that are still part of the standard violin repertoire.

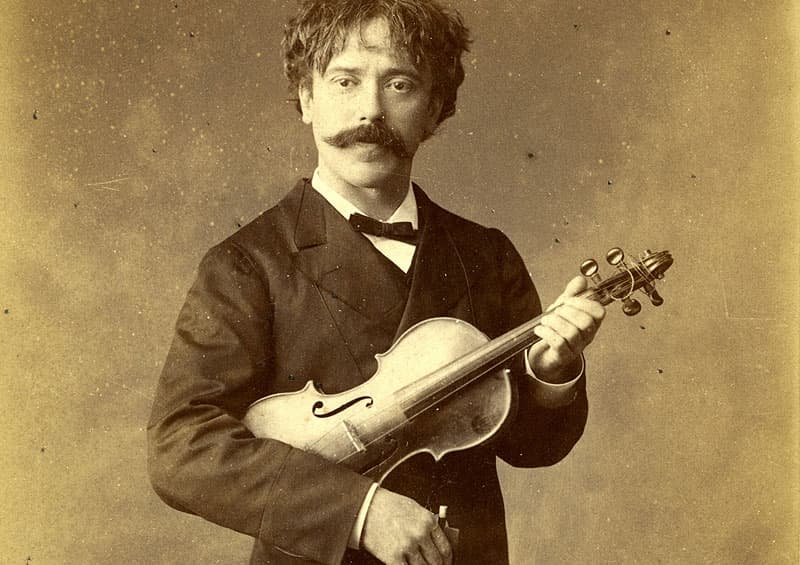

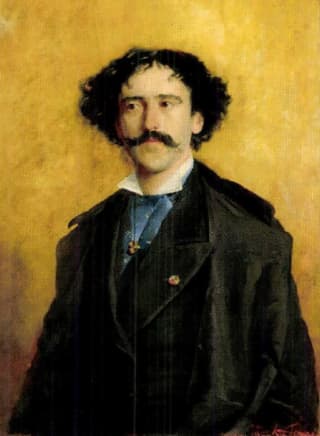

Pablo de Sarasate

The famed Leopold Auer recalls, “Sarasate was a small man, very slender, and at the same time very elegant; his face framed in a fine head of black hair, parted in the middle, according to the fashion of the day… From the very first notes he drew from his Stradivarius I was impressed by the beauty and crystalline purity of his tone. The master of a perfected technique for both hands, he played without any effort at all, touching the strings with a magic bow in a manner which had no hint of the terrestrial.” Given such glowing accolades by one of the most famous teachers in the history of the violin, we decided to have a look and listen to 10 masterworks inspired and dedicated to Pablo de Sarasate.

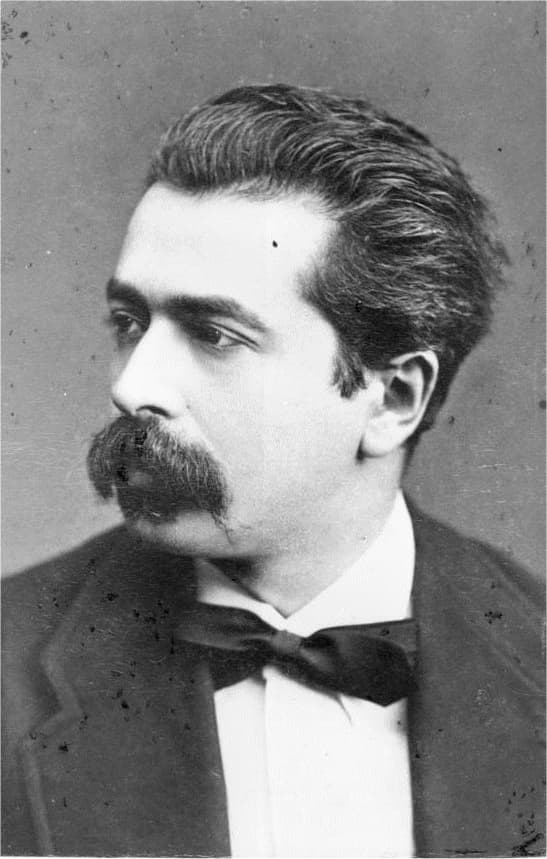

Henryk Wieniawski: Violin Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22

The Russian Music Society, a private musical organization that countered the monopoly enjoyed by the Imperial Theaters, invited young artists of superior talent to perform in St. Petersburg. After his brilliant early successes in Germany, Pablo de Sarasate was engaged by the Society for a number of concerts. Sarasate became an immediate sensation, and since he was only contracted for a limited number of concerts, the public literally fought to obtain tickets.

Henryk Wieniawski

Leopold Auer reports, “One day Davidoff, then director of the Conservatoire, suggested that we visit the Grand Duke Constantine for a little Friday matinee, and Henryk Wieniawski was part of the group. Davidoff presented Sarasate, who, always very reserved and cold with strangers, smiled lightly at the avalanche of compliments. Sarasate exchanged a few cordial words with Wieniawski, whom he greatly admired.” Sarasate was asked to play something so he sent for his Stradivarius which was at the hotel. After playing a few pieces, Wieniawski was asked to play also, so he did, on Sarasate’s violin, which was offered to him. “Sarasate played with ease and tonal charm, which were peculiar to him, standing like a marble statue, his entire vitality concentrated in his eyes, often lowered to his fingers, which moved with astonishing dexterity… Wieniawski played with all his customary fire and ardor, and the first to embrace and felicitate him when he had finished was Sarasate.” Wieniawski dedicated his 2nd Violin Concerto, by many considered his finest work and one of the most popular violin concertos of the Romantic era “to his dear friend Pablo de Sarasate.”

Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Major, Op. 20

Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Major, Op. 20 (Fanny Clamagirand, violin; Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä; Patrick Gallois, cond.)

Camille Saint-Saëns in 1900 by Pierre Petit

In old age, Camille Saint-Saëns remembered, “Years have now passed since there once called on me Pablo de Sarasate, youthful and fresh-looking as the spring and already a celebrity, though a dawning moustache had only just begun to appear. He had been good enough to ask me, in the most casual way imaginable, to write a concerto for him. Greatly flattered and delighted at the request I gave him a promise and kept my word with the Concerto in A major to which, I do not know why the German title of Konzertstück has been given. By playing my compositions throughout the world on his magic instrument, Pablo de Sarasate has done me the greatest possible service and I am pleased to have the opportunity of paying him publicly the tribute of my admiration and gratitude, and of a friendship which follows him beyond the tomb.” Sarasate was only 15 years old at the time, and the single-movement Concerto in A major was, in fact, the second of Saint-Saëns’ violin concerto. Composed in 1858 the work was not published until a decade later.

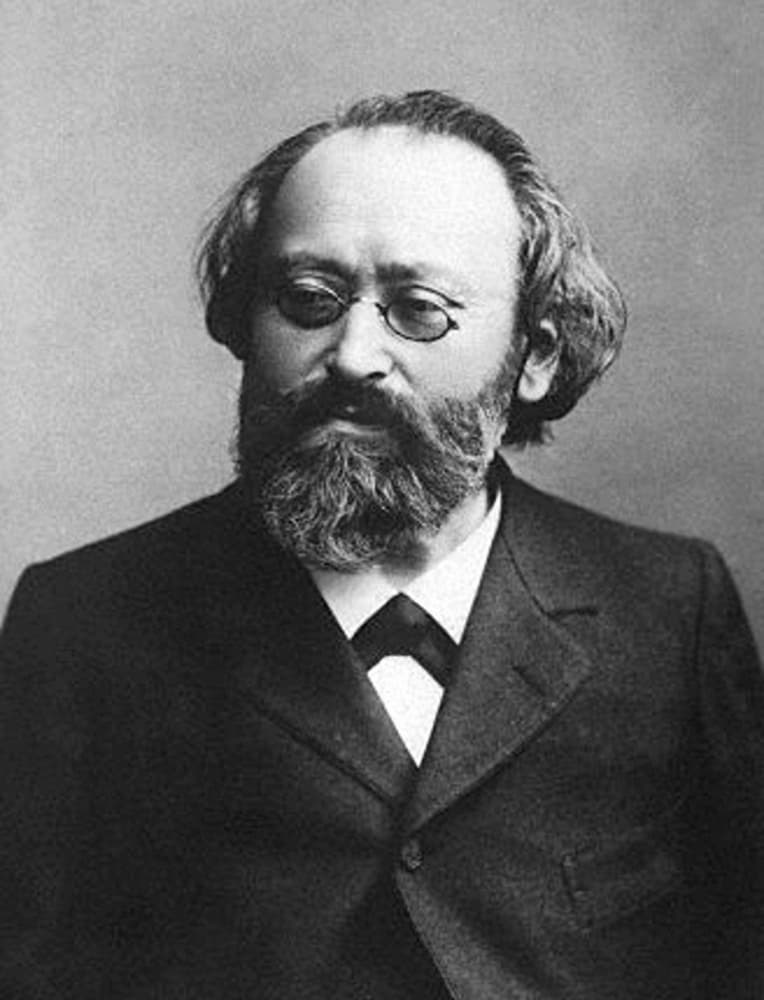

Max Bruch: Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46

It might seem surprising, but the best-known classical violin piece based on Scottish fiddle tunes comes from the hands of the German composer Max Bruch. Bruch had first met Sarasate in 1871, and after a number of collaborations, Bruch wrote to the pianist Otto Goldschmidt, “Yesterday, when I thought vividly about Sarasate, the marvelous artistry of his playing re-emerged in me. I was lifted anew and I was able to write, in one night, almost half of the Scottish Fantasy that has been so long in my head.” Bruch did approach Sarasate for a meeting to collaborate on the new piece, but the violinist was unresponsive.

Max Bruch

Since Bruch did not deal with rejection well, he quickly turned to Joseph Joachim for advice, and Joachim premiered the piece in Liverpool on 22 February 1881. Bruch wasn’t happy, as he considered that “Joachim annihilated the work by performing with insufficient technique and lacking proper feeling.” Luckily, Bruch reconciled with Sarasate shortly thereafter, and Sarasate first performed the Scottish Fantasy on 15 March 1883, with the London Philharmonic in a memorial concert for Richard Wagner. The performance was a resounding success, however, the work all but disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century. It took the brilliant mastery of Jascha Heifetz to once again elevate the Scottish Fantasy to a fixture in the violin repertoire.

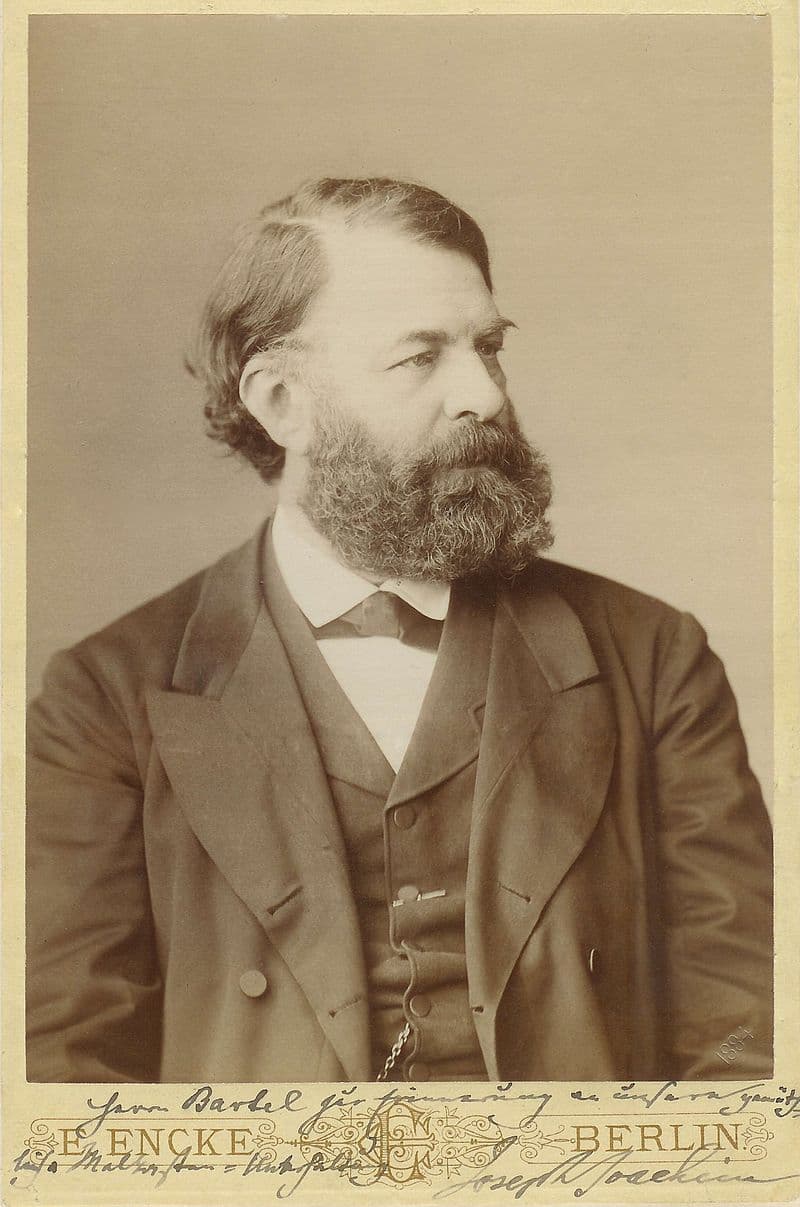

Joseph Joachim: Variations in E minor

Joseph Joachim: Variations in E minor (Hideko Udagawa, violin; Philharmonia Orchestra; Martyn Brabbins, cond.)

Joseph Joachim at age 53

Pablo de Sarasate made his first tour of Germany in 1876. Within the context of the war between France and Germany in the early 1870s, it should not have been a surprise that the musical world was polarized into French and German camps. Sarasate’s initial performances received mixed reviews, and he was unfavorably compared to Germany’s highly esteemed Joseph Joachim. Sarasate took the criticism to heart, and he stormed to the train station on his way to catch a train back to Paris. However, a promoter convinced him to make a final appearance at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, and the performance was a resounding success. While Joachim was conscious of the fantastic skills of the young violinist, the animosity was purely in the eyes of their respective fans. In fact, the two artists greatly admired each other, and dedicated compositions to each other. Composed in 1878/79 and first heard at Crystal Palace in London on 28 February 1880, the Joachim Variations in E minor, amply demonstrate Sarasate’s technical and artistic potential.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Concerto No. 3 in B minor, Op. 61

Camille Saint-Saëns composed his final violin concerto in 1880, a work once again dedicated to Sarasate. “During the process of composition of this concerto” writes Saint-Saëns, “Sarasate gave me invaluable advice, to which is certainly due the considerable degree of favor it has met with on the part of violinists themselves.” Sarasate played the premiere in Paris on 2 January 1881, but he was not satisfied. He felt that it was insufficiently virtuosic to fully satisfy the public or his considerable skills.

Camille Saint-Saëns

However, Saint-Saëns had another great violinist in his back pocket. He had collaborated with the great Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe on a number of chamber works and dedicated to him his first string quartet and the double concerto La muse et le poète, Op 132. Ysaÿe now took up the 3rd violin concerto and his performances took the audiences by storm. Apparently, Sarasate personally heard a performance of the concerto with Ysaÿe as the soloist, and he changed his opinion. In no time at all, it became an integral part of Sarasate’s repertoire. Initially, Sarasate seemed to have missed the fact Saint-Saëns had found a new way of integrating the element of virtuosity. The music is no longer divided neatly into cantabile or brilliant passages, “instead, the virtuoso character can appear at any time, adding drama, excitement or a decorative quality to the music.”

Antonín Dvořák: Mazurek, Op. 49

In January 1879, Antonín Dvořák wrote to his publisher Simrock, “You also want something from me for violin. I’ve got something, namely a concertante piece with piano accompaniment.” Dvořák’s letter was in response to a request for a work in a folk-like style popular at the time. Simrock had requested “a Hungarian or Slavic or Bohemian fantasy or some other new but familiar term! A stylized piece of vivacious virtuosic aplomb that sounds exotically Slavic to western European ears and is intended, of course, for concert performance, with beautiful melodies and other savory ingredients.”

Antonin Dvořák

Dvořák, of course, had previously unleashed a veritable storm on music dealers with his Slavonic Dances published two years earlier. The work Dvořák now had in mind was titled “Mazurek,” basically a Polish folk dance that also appeared under the name “Mazurka.” The work is dedicated to Pablo de Sarasate and was originally cast for violin and piano. Shortly thereafter, Dvořák arranged the piece for solo violin and orchestra. Here as elsewhere, Dvořák succeeded in finding a beautiful mix of folk, classical, and Romantic elements in a style that became the signature of his musical identity.

Max Bruch: Violin Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 44

Max Bruch: Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor, Op. 44 (James Ehnes, violin; Montréal Symphony Orchestra; Mario Bernardi, cond.)

‘

At the beginning of 1877, Max Bruch and Pablo de Sarasate undertook a joint concert tour to London, and Bruch’s First Violin Concerto dedicated to Joseph Joachim was the star of the show. Bruch was very impressed by Sarasate’s playing and he quickly conceived a new Violin Concerto in D minor, dedicated to Sarasate. By early March 1877, he wrote to his publisher that the main melodic ideas were already set. The solo part was first drafted, and eventually elaborated in various rehearsals with Sarasate.

Max Bruch

At the urging of the violinist, the concerto underwent a number of serious changes, which includes “sizeable cuts in the middle movement and a complete rewrite of the ending of the finale at Sarasate’s request,” as the initial version was according to the violinist “insufficiently brilliant.” The Bruch Violin Concerto No. 2 first sounded in public in London on 4 November 1877, with Sarasate as the soloist and Bruch conducting. Early performances were highly successful, although listeners found the opening slow movement unusual. Even Brahms commented, “The final movement of his concerto caused us no small pleasure, but we hope that no imperial decree is necessary to prevent first movements from often being Adagio.”

Alexander Mackenzie: Pibroch Suite, Op. 42

Alexander Campbell Mackenzie: Pibroch Suite, Op. 42 (Rachel Barton Pine, violin; Scottish Chamber Orchestra; Alexander Platt, cond.)

Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935) started out as a violinist and Scots fiddler. He went on to study in Germany and made a name for himself by composing works with a decidedly programmatic or nationalist character. He composed three Scottish Rhapsodies for Orchestra, the Scottish Concerto for Piano for Ignacy Paderewski, and the Pibroch Suite for Sarasate.

Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie

In his autobiography, Mackenzie describes his “dear friend” Sarasate and the first performance of the Pibroch Suite. “To know Sarasate was to love a simple-minded, unaffectedly modest, and generous artist. There cannot be many with a greater claim to speak of his gifts and character, for I enjoyed an intimacy, which revealed the estimable qualities of the musician and man. Easily pleased as a child, in spite of all temptations quite free from vanity, living for his violin alone, he disliked Society, and his joy was to entertain a circle of congenial friends and compatriots; the more the merrier… In my opinion, Sarasate left a deeper mark upon violin playing than any other performer of his day.” The Pibroch Suite premiered at the Leeds Festival in 1889 with Sarasate as the soloist under the composer’s baton.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28

Rounding out Sarasate’s influence on Camille Saint-Saëns we turn to the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso in A minor. Composed in 1863, it originally was intended as the rousing finale to the First Violin Concerto. In the event, it was published as a self-contained, single-movement work tailor-made for Pablo de Sarasate.

Pablo de Sarasate

The premiere took place on 4 April 1867 at the Champs-Élysées, with Sarasate playing the solo part and the composer conducting. It is still considered one of Saint-Saëns’ best-loved works, and it is frequently paired with his Havanaise dedicated to another friend, the Cuban violinist Rafael Diaz Albertini. His Op. 28 is frequently described as a “brilliant showpiece,” and Saint-Saëns writes at the end of his life, “If my violin music was so successful, I owe it to Sarasate, because he was for a time the most prominent violinist in the world and he played my works, which were still unknown, everywhere.”

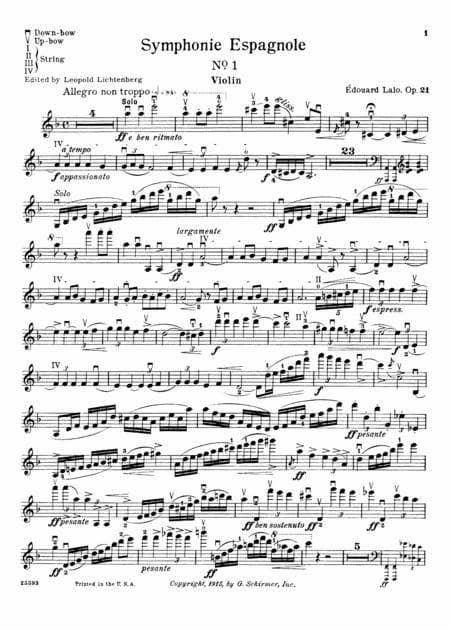

Édouard Lalo: Symphonie espagnole

In March 1878, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patron Nadezhda von Meck. “Are you familiar with the Symphonie Espagnole by Lalo, a French composer? This piece was made fashionable by the violinist Sarasate. It is scored for violin solo with orchestra and is made up of a sequence of five independent movements, which are based on Spanish folk tunes. I have received a lot of pleasure from this work. It has a lot of freshness, lightness, piquant rhythms, as well as beautifully and splendidly harmonized melodies.”

Music score of Édouard Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole

In fact, the Symphonie Espagnole is not a symphony, nor is it Spanish. We might also be stretched to call it a concerto, but it is at any rate a fabulous showcase for the violin. Genre designations aside, it might well have prompted Tchaikovsky to start working on his own violin concerto. Lalo actually hailed from Lille, and with his Symphonie Espagnole he opened a window unto the extraordinary virtuosity and artistry of Sarasate. Premiered in 1875, the work beautifully reflects the persona of Sarasate, “who personally was mercurial, and as a musician, the kind of extraordinary virtuoso who valued musicality and meaning above the empty showmanship, playing with lyricism, with, and a certain fire.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter