It sits there in the corner of the living room, dark, foreboding, and challenging all to make it show its true potential. The key home instrument for the rising middle class was the piano.

Grand Piano

The mark of gentility was knowing how to play it: witness the times in Jane Austen when a character’s piano playing was indicative of their personal qualities. In Pride and Prejudice, for example, Miss Darcy is described as ‘…so extremely accomplished for her age! Her performance on the pianoforte is exquisite’. Elizabeth Bennett’s sister Mary on the other hand, has her character revealed through her poor playing: ‘Mary had neither genius nor taste; and though vanity had given her application, it had given her likewise a pedantic air and conceited manner, which would have injured a higher degree of excellence than she had reached’.

One of the solutions to the monster in the corner was to have someone else play it and the invention of the Piano Player, later called the Pianola, and later yet, the Player Piano. The earliest piano players were separate instruments that played via a piano roll and were placed in front of an existing piano and pushed down its keys.

Pianola in front of a piano, 1898

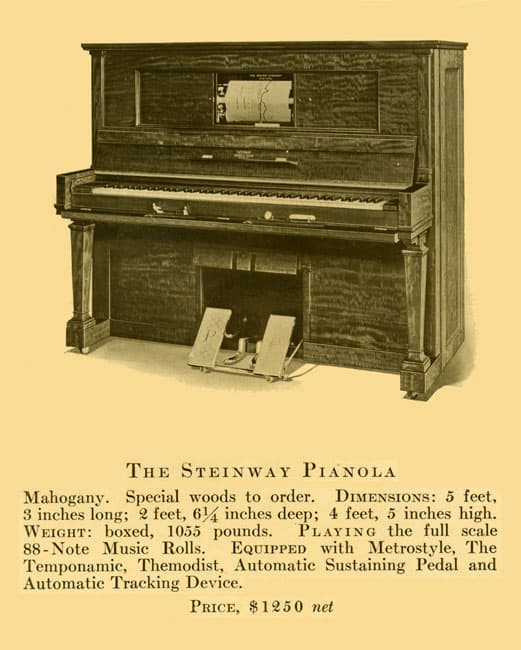

Eventually, these ‘push-ups’, as they were called, were replaced by a mechanism built inside a regular piano – created by the Aeolia Company in New York, these were trademarked as the Pianola. In this Steinway Pianola, the center can be opened to show the piano roll, the plate in front of the keyboard opens for the pianola controls (speed, dynamics, etc.) and foot pedals for driving the mechanism could be placed in front of the regular piano pedals.

The Steinway Pianola, 1914

The copyright word Pianola gave way to the more generic Player Piano and so these instruments invaded the living rooms.

The Music Rolls placed in the piano, were, contrary to belief, not created on the keyboard, but were created by a technician working from a score. One of the problems with the piano rolls was that they ran at a constant rate and the things that make piano music evocative, such as phrasing, rubato, dramatic pauses, etc., couldn’t be controlled by the roll. That’s where the artistry of the pianist and the controls at the front of the keyboard came into play. The breadth of a piano roll covered 65 notes (an appreciable percentage of an 88-key piano keyboard). One of the reasons for opening the front of the piano to expose the piano roll was to provide instructions to the pianist for adding the details: in this roll for the opening of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, the dotted line on the edge shows the pianist how to control the dynamics. The roll is marked ‘Allegro’ and ‘90’ (meaning a speed of 9 feet per minute of the roll) in blue in the center bottom, with the fermatas marked on the 4th note.

The opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony on a piano roll

The Mystery Piece is Beethoven’s 7th First Mvt. 4 Hand Player Piano Roll

The next advancement was to capture the nuances of a performance on a piano roll. This was accomplished in 1904 in Germany with the Welte-Mignon piano. These ‘reproducing pianos’ could capture ‘the rubato, dynamics and pedalling – in short, the complete performance – of the pianists who recorded for them. Nearly all the major pianists of the early twentieth century made rolls for the reproducing piano…’. This recording of Artur Schnabel was made in 1905 on a recording piano and then made into an audio recording in 2001 using a Welte-Mignon piano.

Carl Maria von Weber: Aufforderung zum Tanze (Invitation to the Dance), Op. 65, J. 260 (Artur Schnabel, piano)

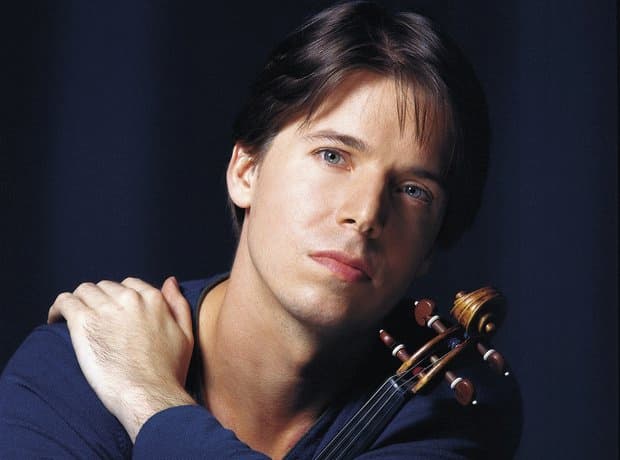

It would be possible to have the piano part recorded and then play a solo part on an instrument, such as this collaboration between Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) and Joshua Bell (b. 1967).

Joshua Bell

Edvard Grieg: Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 45 – II. Allegretto espressivo alla romanza (Joshua Bell, violin; Sergei Rachmaninoff, piano)

The potential of the Pianola started to have composers to be attracted to write for it, including Stravinsky, Hindemith, Milhaud, Percy Grainger, and Herbert Howells. This use of a player piano meant that the composers could write music that no human hand could play – and this will become important later.

Stravinsky at his Pleyela player piano, 1923

Igor Stravinsky: Pianola Etudes (Rex Lawson, pianola)

Stravinsky made arrangements of his music for player piano, including Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring, The Song of the Nightingale, Pulcinella, Les Noces, and other works, and these were published in Paris.

The Rite of Spring: “Adoration of the Earth – Introduction, Pt. 2 (Piano roll: Igor Stravinsky; Pianola: Rex Lawson)

By the 1930s, the player piano’s age had come to an end, sales of the instrument really ended by the Depression. Starting in the 1940s, however, American composer Conlon Nancarrow found inspiration in player pianos, finding that he could create works that, truly, were unplayable due to their speed and technical demands by regular pianists. He had his own roll cutter machine and also adapted player pianos, changing their sound by covering the felt piano hammers with other materials, such as leather or metal (taking a cue from John Cage’s work with Prepared Pianos). He took styles, too, from jazz and pianists such as Art Tatum. This culminated in his Studies for Player Piano, written between 1938 and 1992.

Conlon Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 3a (Conlon Nancarrow, piano)

All these attempts to conquer the art of piano playing and then transcending it by creating works that no one except the player piano mechanism could play is rather like an entire review of the 20th century in one instrument!

For a close look at how involved a pianist has to be with the true art in a piano roll, see this video of Rex Lawson playing the second movement of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony. As always, an instrument in the hand of a master tells us more than just knowing, technically, what is supposed to be happening. You will note a couple of things: more than 10 notes are being played at once and often the distance between notes is beyond the scope of even the largest hand span.

Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2, Second Movt – Pianola arrangement by Rex Lawson

For more information on player pianos and more videos of them in action, see The Pianola Institute website.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter