The historically informed performance movement has opened up the realm of interpretation by enriching the subjectivity of artistic expression with the objectivity of scholarly study. And while critics have suggested that such performances are not really historical but a performance style that is completely of our own time, dedicated scholars, conductors and performers continue to infuse the sounds of yesterday with the artistic concerns of today.

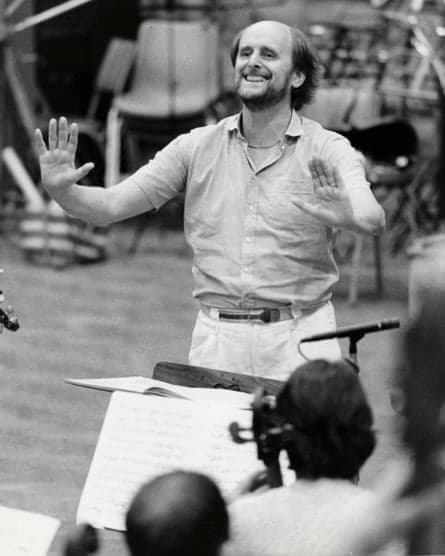

Sir Roger Norrington

The English conductor Roger Norrington, born in Oxford on 16 March 1934, became an important voice in this particular performance movement. You see, the historically informed performance movement arose in the latter half of the 19th century as a reaction to the way modern techniques were imposed upon music of earlier times. However, it was Norrington who extended the concept of “period performance,” to the music of the 19th century. He founded his own period orchestra, the London Classical Players, and by probing scores, orchestral sound and size, seating and playing styles, Norrington brought an entirely new soundscape to the core of the orchestral repertory from the Romantic era.

Roger Norrington Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 8, Op. 93

The Musical Childhood Years

Roger Arthur Carver Norrington grew up in a highly musical family of Oxford scholars. He was a talented boy soprano, studied the violin from the age of ten, and singing from 17, but his higher education was in English Literature at Cambridge. Norrington was active as a violinist, tenor and conductor for several years, before returning to his studies at the Royal College of Music under Sir Adrian Boult. In 1962 he made his conducting début with the “Heinrich Schütz Choir,” an ensemble he founded and one he would lead for roughly 30 years. Within the context of choral conducting, Norrington began his exploration of historical performance practice, and he produced numerous innovative recordings for Argo/Decca. The London Baroque Players first accompanied performances by the “Schütz Choir,” but as the period of rediscovery moved forward, the London Classical Players became the preferred partner. “When Norrington reached the era of the symphony in his researches, the LCP took on a life of its own and the Schütz Choir went into semi-retirement.”

Domenico Scarlatti: Stabat Mater (Heinrich Schutz Choir; Charles Spinks, organ; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Norrington’s Path Towards Historically Informed Performances

Sir Roger Norrington, Steve Reich and Vladimir Jurowski awarded honorary doctorates by the Royal College of Music

The path towards historically informed performances was a gradual process. As Norrington explains, “Until the 1960’s, it was always the creative thing to make the music the way you feel it now. For instance, when Mozart edited Handel, he made it sound like Mozart. He did not have any notion that Handel should sound like Handel. He thought it should be updated, that it should be made fit for modern taste. That elastic band that stretches from around 1750 until today breaks at certain points, and around 1960 it broke completely. We went back and found out something about what it sounded like then. To our surprise, it did not sound poverty-stricken but had tremendous punch. Hearing a great performance of Bach on original instruments had the most amazing qualities of newness.” Norrington then used the same approach to music of the Nineteenth Century, approaching it via the Baroque rather than from the Twentieth Century.

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 (London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Norrington does make it clear, however, that there is no such thing as an authentic style. “Essentially, it’s directly informed performance practice. Every conductor wants to do the music like the composer does. It’s just that as the composers get further and further away, and as our styles develop, we simply need to get a bit more basic information.” Norrington is generally upbeat on the future of music, in both performance and creation. “Composing can only get better than it’s been for the last twenty years… with some particular exceptions apart. There’s such a lot of incredibly bad and boring music that’s been written, soulless, heartless above all that’s been written and inflicted upon us, that we’ve really had to sort out the heartier from the unhealthy.” Norrington strongly believes that if we elect governments who take music out of schools, then music will disappear in some areas. “If we turn it into what people call in England an upper-middle class ghetto where everything is luxury packaged, it will lose its nutrients; it will lose its vitamins. Music is a food, and we need it. We don’t necessarily need terribly intellectual music; we need good, strong, hearty, credible music. Then people will go on writing it, and people will go on listening to it.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Norrington Conducts Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique