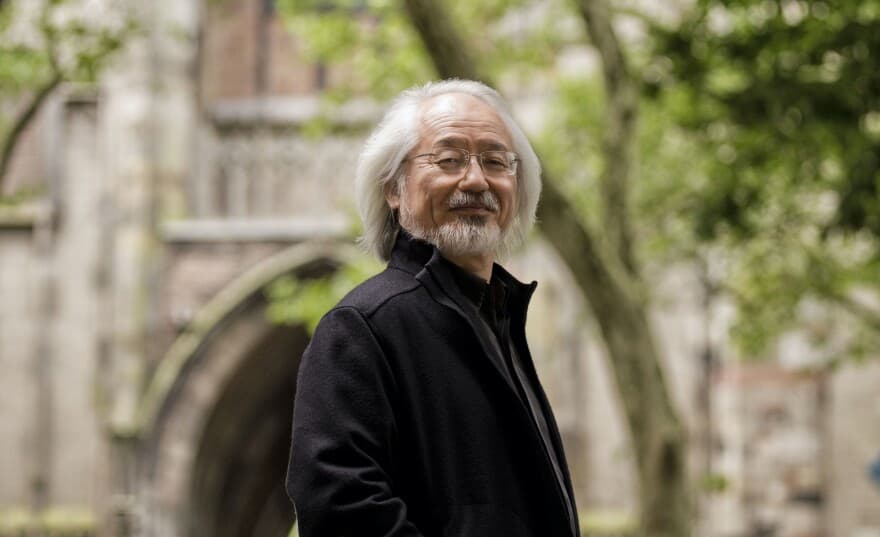

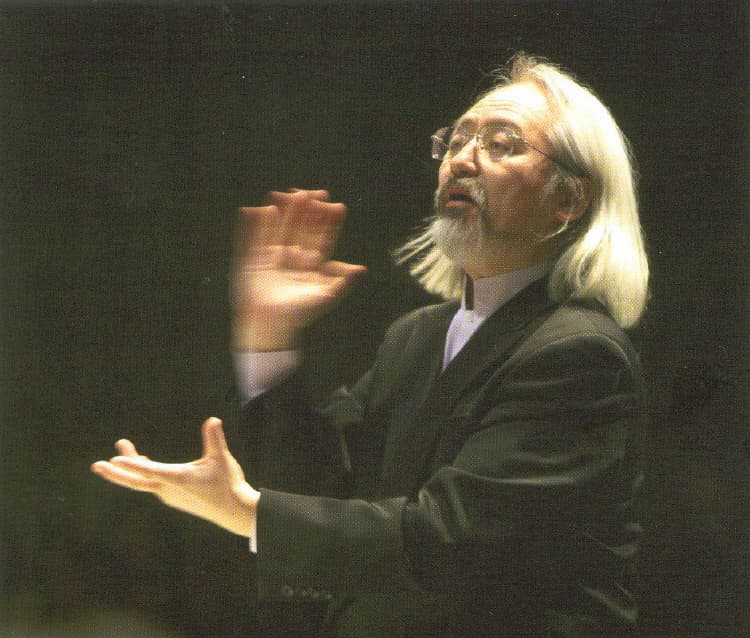

Masaaki Suzuki, born on 29 April 1954 in Kobe, founded the Bach Collegium Japan in 1990. He simply wanted to introduce Japanese audiences to period instrument performances, and “to keep performing Bach cantatas one by one.” The ensemble began to give concerts regularly in 1992, and they produced the first recordings in 1995. By 2013, they had recorded a 55-volume series of the complete Bach church cantatas for the Swedish label BIS Records.

Masaaki Suzuki

Initially, there was some skepticism, but Suzuki explains, “Bach’s music is a universal language that can easily overcome any kind of cultural border. He is one of the most famous European composers in Japan. Every child who starts playing the piano plays Bach at some point, and everybody who goes to a conservatory has to study Bach. Nobody is a stranger to Bach’s music.” Suzuki was born to Protestant Christian parents, both amateur musicians. His father had at some point worked professionally as a pianist, and “without this background, I probably wouldn’t have come to this field at all.”

Masaaki Suzuki/Bach Collegium Japan Perform Bach’s Cantatas BWV 29, 30, 120

Suzuki remembers, “ When I was in middle school, I started playing the organ every Sunday during worship. I enjoyed it very much and tried to play all of Bach’s organ works, but the organ was actually only a small, pedal-pumped harmonium; it was impossible to play Bach on that. So I decided that I had to play a real organ, and took lessons in high school. My first teacher was a Belgian Catholic priest who was also a musicologist, specializing in 15th- and 16th-century polyphonic music. I wouldn’t have started this without my religious background. I have always felt a familiarity with Christian music and culture, and not only the worship. I can’t say that I am very religious, but I believe in God. But I definitely believe in the power of music, and especially in Bach’s sacred works.”

Bach Collegium Japan

Suzuki’s love affair with Bach started when his father brought home a recording of the Mass in B minor conducted by Karl Richter. “It came as a great shock to me,” explained Suzuki. “It was a revelation, even though I couldn’t understand then what it meant. I listened to it every night after my family went to sleep. I couldn’t stop.”

Masaaki Suzuki/Bach Collegium Japan Perform Bach’s Mass in B minor, “Dona nobis pacem”

Suzuki went on to study composition and organ at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, and he earned soloist diplomas at the Sweelinck Conservatory in Amsterdam. He studied harpsichord and organ with Ton Koopman and Piet Kee, and improvisation with Klaas Bolt. He was hired as a harpsichord instructor at the Conservatory in Duisburg, Germany from 1981-1983, and subsequently returned to Japan to teach at Kobe Shoin Women’s University.

Masaaki Suzuki

Suzuki was fascinated by the fact that Bach’s music is no longer part of a church service, but instead good music for the concert hall. For Suzuki, this actually tells us something about the Bible, “as the message can also be spread outside of the service. And I learned how to see culture in the world. When we perform a Bach cantata in a Tokyo concert hall, many people listen, primarily enjoying the beautiful music. Others, on the other hand, consciously experience this as a biblical message. I always find this mix fascinating.”

Masaaki Suzuki Plays Bach’s “Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr,” BWV 663

Suzuki does not see a big difference between the understandings of the text of a Bach cantata now and then. “The biblical message as a basis is equally there, even if the theology is different today. Of course, German culture is just as alien to us Japanese as baroque ways of thinking. In this respect, I don’t even need to know which sentences are difficult for today’s Germans to understand—everything is difficult for the Japanese to understand. We have to translate all the sentences into Japanese anyway for a performance and then discuss what they mean so that we can understand the message, which hasn’t changed to this day.”

Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

Having worked with both Japanese and European performers, Suzuki strongly believes that Bach’s music speaks across cultural boundaries. “We can appreciate it as pure music,” he says. “Of course, without the religious aspect, we are missing the most important part of what Bach has to say, but the combination of the sacred voice parts and his great instrumental writing adds up to a wonderfully rich experience.” It is not Suzuki’s job to re-export Bach back to the West, but he continues to be fascinated by the challenge of encouraging audiences elsewhere in Asia to open their ears.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Masaaki Suzuki/Bach Collegium Japan perform Bach’s St. John Passion, BWV 245 (excerpts)