On 9 May 1965, famed pianist Vladimir Horowitz gave a recital at Carnegie Hall.

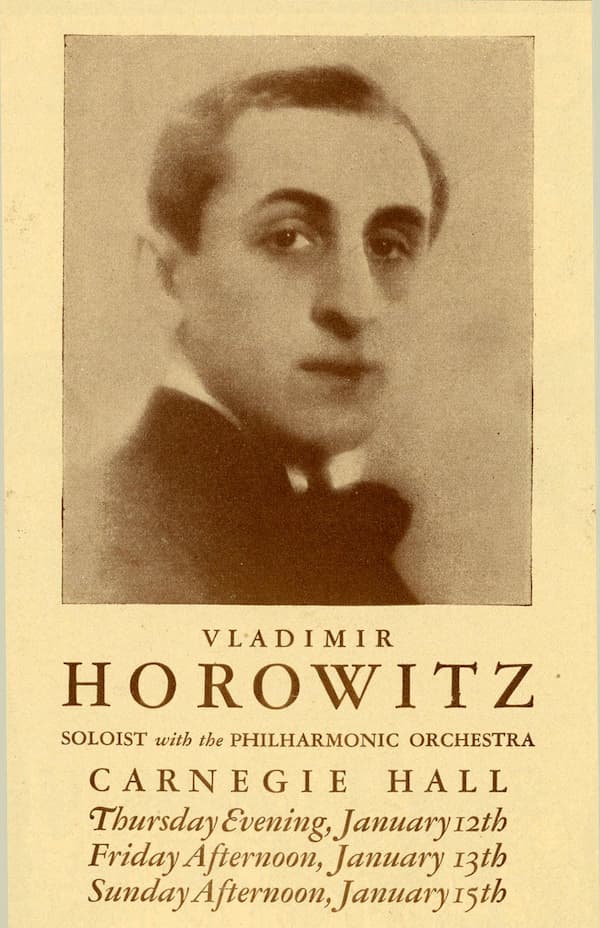

Horowitz 1928 Carnegie Hall program

But this was no ordinary Vladimir Horowitz recital. Due to depression and anxiety, he had not appeared in public since 1953. The entire musical world wanted to know: does he still have it?

When May 9 finally arrived, his fans packed the hall. They chattered in a mix of English, German, Italian, and other languages.

The stars of the classical music world took their seats: Rudolf Bing, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera; pianists Van Cliburn, Gary Graffman, and Abbey Simon; and conductors Leonard Bernstein and Leopold Stokowski.

Meanwhile, audio engineers readied their equipment. Columbia Records was on hand to immortalise the performance.

The pressure facing Horowitz in this moment was extraordinary, and unlike anything he’d ever experienced in his career. Could he meet the moment?

Turns out, he could. The 1965 Vladimir Horowitz Carnegie Hall comeback concert would become one of the most famous recitals in classical music history.

Horowitz’s History with Carnegie Hall

Horowitz at Carnegie Hall

Vladimir Horowitz was no stranger to Carnegie Hall. Over the course of his career, he played there almost a hundred times.

He made his American debut there on 12 January 1928 with the New York Philharmonic under Sir Thomas Beecham, playing Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto.

Horowitz was just 24 years old at the time, fresh from the Soviet Union and attempting to make a name for himself in the West.

It wasn’t long before he became one of the most popular piano soloists in the world.

Meeting Wanda Horowitz

The Horowitz / New York Philharmonic partnership would prove to be personally, as well as professionally, consequential.

In 1933, Horowitz performed at Carnegie Hall again under the Philharmonic’s exacting music director, Arturo Toscanini. After the concert, Horowitz met Toscanini’s daughter Wanda.

Despite Horowitz’s homosexuality, he was drawn to her, and she to him. They cemented their connection at a post-concert after-party when Horowitz played a Chopin mazurka, and Wanda remarked that she’d never heard anyone play a Chopin mazurka quite like that.

Eight months after they met, they married. In 1939, he moved to New York, and in 1944, he became an American citizen.

Horowitz’s Mental Health Struggles

Horowitz and Wanda

Horowitz suffered from depression and anxiety. His stage fright was intense: he often had to be pushed onstage before he would play.

His poor mental health, combined with his struggles with his sexuality and Wanda’s strong (some claimed abrasive) personality, led his marriage to deteriorate. In 1948, the couple separated, and Wanda started dating one of Horowitz’s students.

He hit rock bottom in 1953 and had a breakdown. At that point, Wanda returned to his side to nurse him through the crisis. He decided to take some time away from the concert stage.

In lieu of touring, he made some recordings in his New York City townhouse. Some of his anxiety was quelled by not having to perform in front of a live audience.

Wanda stayed by his side as year after year passed. She later explained to a reporter, “I went with him through very difficult times. For 12 years he was not playing and for 12 years I heard ‘I will never play again,’ and I kept silent. I never prompted him, pushed him to play.”

During this time, the family’s financial situation grew bleaker. To get by, Wanda sold valuable paintings that they had collected during better days.

Making the Decision to Return to the Stage

By early 1965, Horowitz felt that he had improved his mental health and was ready to return to the stage. He booked Carnegie Hall for a recital and secretly began rehearsing there.

He worried that the public had forgotten him after a decade-plus break from the world’s concert stages.

He needn’t have been. People camped outside the hall overnight – in some cases, for days – to get tickets. The entire hall sold out in two hours. Wanda Horowitz came by the line with coffee.

Rehearsals for the Comeback Concert

We are lucky that recordings document various aspects of this historic comeback concert.

Audio from January rehearsals was recorded and is easily accessible today.

These are fascinating documents. They begin with Horowitz improvising in a full-throated Romantic style, getting a feel for the instrument and the hall.

It is clear from just the first few phrases that, despite his time away from the concert platform, he had retained his abilities.

Vladimir Horowitz : Carnegie Hall Rehearsal, 7 January 1965

In these casual recordings, you can hear Horowitz chatting with other people and soliciting their opinions.

“It sounds very good in here,” the audio engineer says.

“Does it?” Horowitz asks. “I want to try how it sounds. I stop anywhere, anytime. It’s just me now.”

Later, he asks, “You have this whole business on tape, yeah? Let’s proceed. I may stop, you know. I don’t know. Anything can happen!”

Horowitz returned for other rehearsals before the big day, which was scheduled for 9 May 1965.

The Comeback Recital

Horowitz at Carnegie Hall, 1985

On May 9, the throng of concertgoers arrived in a whirlwind of breathless excitement.

They arrived in the hall to find that it was as warm as a sauna. Turns out, Columbia Records had insisted on the air conditioning being turned off so the humming sound wouldn’t affect the recording.

Some people were skeptical that Horowitz would show up at all. For a while, it seemed as if their concerns were justified. The concert was scheduled for 3:30, and ten minutes before showtime, Horowitz still wasn’t there. However, at 3:25, he finally arrived, stepping into the building on Wanda’s arm.

Horowitz – The Historic 1965 Carnegie Hall Return Concert

The program was as follows:

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C Major, BWV 564, originally for organ and arranged for piano by Busoni

- Robert Schumann: Fantasie in C Major, Op. 17

- Alexander Scriabin: Piano Sonata No. 9 in F Major, Op. 68, “Messe noire”

- Alexander Scriabin: Poème in F-sharp Major, Op. 32, No. 1

- Frederic Chopin: Mazurka in C-sharp Minor, Op. 30, No. 4

- Frederic Chopin: Étude in F Major, Op. 10, No. 8

- Frederic Chopin: Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23

He came onstage to curious applause.

His opening nerves led to some mistakes in the Bach/Busoni, but in the official recordings, takes from rehearsals were spliced in to rid the program of errors for future listeners. A recording was later released with the original live take.

But after he found his footing, he gave an extraordinary performance that transfixed all 2800 people in the hall.

Encores – and the Rapturous Audience Response

The applause was rapturous, and he gave four encores:

- Claude Debussy: Children’s Corner, L. 113: 3. Serenade for the Doll

- Alexander Scriabin: 3 Pièces, Op. 2: 1. Étude in C-sharp Minor

- Moritz Moszkowski: 15 Etudes de Virtuosité, Op. 72 No. 11. Presto e con leggierezza

- Robert Schumann: Kinderszenen, Op. 15: 7. Träumerei

During these pieces, Horowitz’s performances were interrupted by the clicks of cameras. Several fights broke out. “Horowitz is more important than your pictures,” one person said. The crowd was unaware that he had given permission to photographers ahead of time to document the historic moment.

Even after four encores, the crowd wanted more. But finally, the stage lights turned off, the house lights turned on, and the piano lid was shut. Audience members groaned in disappointment. Hundreds of them then migrated out to 56th Avenue in an attempt to cheer Horowitz as he left the hall.

Press Reaction

The next morning, the New York Times ran a front-page headline: “Vladimir Horowitz, Pianist and Legend, Plays Again; Absence of 12 Years Ends in Triumph at Carnegie Hall.”

In his lede, reporter Murray Schumach proclaimed the concert “one of the most dramatic musical events in recent musical history.”

His review focused less on the performance and more on the cultural implications of Horowitz’s long-awaited return to the stage. (There was a whole separate review written by New York Times classical music critic Harold Schoenberg, praising the concert in-depth.)

“Men and women who remembered his pre-retirement phase said he seemed much more cheerful than in the years before he stopped playing for the public,” Schumach reported. Schoenberg made a similar comment in his review.

Horowitz’s Legacy

Although Horowitz continued to struggle with his mental health for the rest of his life, and would even take additional yearslong breaks from the stage, none of those breaks lasted as long as this one had.

In 1968, he returned to Carnegie for a televised performance.

Horowitz – The 1968 TV Concert

He played his last concert in 1987, at the age of 84. Over a career that lasted for six decades, he cemented himself as one of the greatest pianists not just of his generation – but of all time.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter