American composer George Rochberg (1918–2005) occupied a difficult ground in 20th-century modern classical music. Caught between the serial composers of the mid-century and the gradual return to tonal music that followed, he abandoned his long-held serial style after the death of his teenage son in 1964, finding that, although intellectually satisfying, it didn’t fill his emotional needs. But his inclusion of tonal passages in the 1970s also elicited comment from his contemporaries, particularly as he started to include quotations of music from other composers, including J.S. Bach.

George Rochberg

His 1971 work, Carnival Music, is unusual in his output in that it looks back to his early music-making as a jazz pianist in the 1930s.

It opens with a Fanfare and March, which is less a fanfare than a call to a serialist audience. Little phrases pop in and out and are repeated until the March gets underway. Now, we seem to be part of a circus parade, with much to distract us, including the musicians, as the music is often off its own fixed beat. There are parts that sound like Stravinsky’s Petrushka, another work set in a circus environment.

George Rochberg: Carnival Music – I. Fanfares and March (Sally Pinkas, piano)

The Blues movement starts out with all the right sounds, but then quickly becomes informed by 20th-century ideas. It’s the blues, but in the hands of a highly educated master. What he has created is a mix of genres – blues, but within the form of a variation set.

George Rochberg: Carnival Music – II. Blues (Sally Pinkas, piano)

At the heart of the work is Largo doloroso, which removes us from the realm of popular music and takes us somewhere entirely different. Melancholic and dreamlike, pensive and distracted, the movement seems to get behind the glam and glitter of the first two movements.

George Rochberg: Carnival Music – III. Largo doloroso (Sally Pinkas, piano)

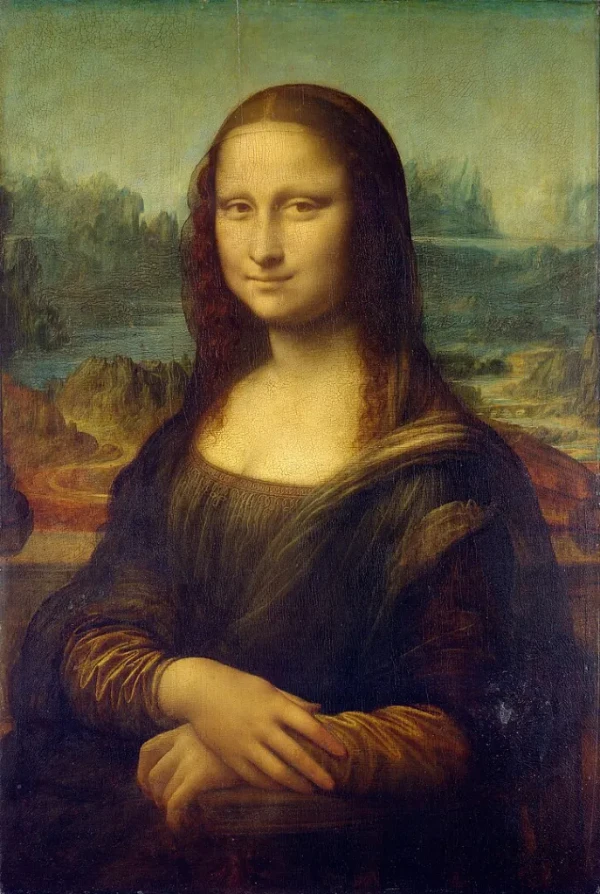

Sfumato is a technique from the 16th century art, invented by Leonardo da Vinci, where an object is given volume through light and shadows, rather than through sharp boundaries. Some of the most famous paintings in history are in this style, including Mona Lisa by da Vinci and The Girl with the Pearl Earring by Vermeer.

Leonardo da Vinci: Mona Lisa, 1503–1519 (Paris: Louvre)

Vermeer: Girl with a Pearl Earring, ca 1665–1666 (The Hague: Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis)

In this movement, Rochberg starts with casting a smoky background out of which emerges sounds from the past, including elements from Brahms’ Capriccio, Op. 76, No. 8 and Bach’s triple counterpoint Sinfonia No. 9 in F minor, BWV 795. The bass creates the ‘misty, veiled, dreamy background’ while the right hand delicately picks out the melodies.

George Rochberg: Carnival Music – IV. Sfumato (Sally Pinkas, piano)

The work closes with another summoning of popular culture. The Toccata-Rag returns to the composer’s popular music-making of 40 years earlier.

George Rochberg: Carnival Music – V. Toccata-Rag (Sally Pinkas, piano)

Rochberg was controversial for his inclusion of well-known works by well-known composers in his own works, coming against the 20th century’s overriding demand for originality. Yet, in a work such as Carnival Music, those quotations have a way of evoking the past while not letting the past override the present. The contrasting middle movements, which seem full of introspective reflection, and the exuberant outer movements present an interesting contradiction in a single work. It’s both pop and serious, extroverted and introverted, and in the end, highly satisfying.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter