Dame Myra Hess (1890–1965) is known to most people today as the face of the famed WWII concerts held in the National Gallery in London. Jessica Duchen’s new biography reveals the personality behind the picture, and it is a key to the modern life of classical music in a way that few people have put together before.

Myra Hess performing at the National Gallery

Each quarter of her life took her to new areas, from Edwardian rebel to Bohemian and feminist and, in the end, to American piano superstar.

Although audiences regarded her as having a ‘giant, rock-like presence’, the pianist stood only five foot, three inches (160 cm) in height and led a life-long fight to get piano stools that worked for her, sometimes requiring that too-tall ones be sawn off at the legs so she was sitting correctly.

Her father was heir to his family’s textile factory in Spitalfields that was known for their manufacture of the peaks for military and police caps. Members of London’s Jewish community, the Hess family kept the religious traditions, and Myra would continue to watch them throughout her life. She avoided concerts on Jewish holy days and lamented that her own concert schedule prevented closer attention to the rites.

At the end of the 19th century, the musical world was full of amateurs, from music teachers to choruses. Musical performances in the church were more highly rated than professional careers, such as when the well-to-do family of Ralph Vaughan Williams opposed his dream of becoming an orchestral viola player. Native musicians often found the musical life abroad in Paris or Vienna more encouraging than life in London. Home-grown was underrated.

Myra was the youngest of four children who all learned music, the piano for all of them, and also the violin and cello. Myra’s advancement in piano was noticed immediately, and it was thought that a more advanced teacher was brought in. Her first public concert was at age 8, and her last was when she was over 70. Between those years, she made wonderful music.

In 1903, she entered the Royal Academy of Music, where she became the student of Tobias Matthay, who was to be a primary influence on her music. As she said, ‘At the age of thirteen, I thought I was an accomplished pianist. But then I became a pupil of Tobias Matthay and discovered that I was just beginning to learn about music’. He took from someone who played the piano well to someone who could look at the ‘musical intention and significance of every sound one made, and all his vast knowledge was directed towards one goal: the true expression of music’. His admonition to his students before a performance was ‘Enjoy the music’, and with that in their ears, his students took to the stage filled with confidence.

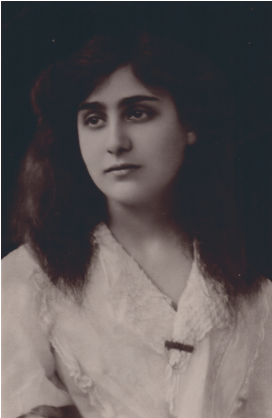

Myra Hess, ca 1907

Myra Hess made her official debut at the Queen’s Hall on 14 November 1907 with Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in G and Saint-Saëns‘ Piano Concerto in C minor. The young Sir Thomas Beecham conducted the New Symphony Orchestra. Critics noted the 17-year-old’s technical facility and ability to bring out the poetry in slow movements.

Despite this promising beginning, success was slow to come, as many performers find. Hours of teaching were necessary, and she started to make her name through a self-funded annual recital in London. She made her debut in the Aeolian Hall on 25 January 1908, with a performance of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor arranged by d’Albert; Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, Franck’s Prelude, Chorale and Fugue; a selection of Brahms intermezzos; Chopin’s Ballade No. 3; and two pieces, Albumblatt and Elves, by her teacher Matthay.

The first of her 90-some Proms appearances took place on 2 September 1908, playing the Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1, with Henry Wood conducting.

As Myra approached her 20s, the question of career or family raised its head more than once, but Myra’s uncompromising position meant that sacrificing her all-in commitment to music meant not only that she never married but also that she commented on other talented musicians’ choices. She commented in 1938 ‘I’m afraid I would be too earnest about marriage, and in this business, there is only one thing one can be really earnest about. That is playing the piano. One sacrifices a great deal, but there are compensations’.

Gradually, Myra’s name became known. A last-minute substitution for an ailing soloist gave her a performance in Amsterdam at the Concertgebouw and gained her the attention of Willem Mengelberg, its chief conductor. She impressed him, and he remained a faithful supporter for the rest of his life. The start of her Dutch career meant an improvement in her finances. Where a performance in London might bring her the fee of three pounds and three shillings, a recital two months later in The Hague brought her £15. A year later, she was paid £30 for a concert with the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

At home, the family finances were collapsing, and her father, the former owner of a textile mill, was reduced to being its manager. Stock market losses and Myra’s lack of performance (only 24 in 1911), combined with a lack of an aggressive business manager to demand higher fees, led to the family constantly moving from less expensive to less expensive apartments. Her father suggested that, instead of these expensive recitals, she should consider going into a music hall. She should not be making her life in music. She left the family home to set up her own house. As the author wryly noted: ‘Finding somewhere to live as a single woman of 24 with a grand piano in 1914 was no easy task’.

Note the year. 1914 was a year of unrest in England. There were social and class problems; 30% of Londoners lived in poverty, strikes were everywhere, and suffragettes were demanding a stronger voice for women in society. The start of the war in August brought even more problems to the fore as the world turned toward shadows.

In music, anti-German sentiment came to the fore: Bechstein had its company assets seized, along with those of other German-owned companies, Bechstein Hall was closed, sold to the Debenhams group and reopened under the name of Wigmore Hall. Russian-surnamed musicians changed their names. Myra’s performances stopped until November, when a normal life might be approached again.

In 1915, stability came with creating a home with four friends in St John’s Wood. Myra and four of the Compton-Burnett sisters split a villa, each family with their own staff. She would live there for the next 20 years.

Now set up with a stable home situation, Myra’s music-making increased. A 1916 tour to Holland brought 25 concerts in 2 months, including many solo recitals and concerts shared with other instruments. At home, for the other 10 months, she gave a further 25 concerts – a sorry comparison.

She started work in 1916 with the violinist with whom she would work for the next 24 years: the Hungarian Jelly d’Arányi. They would remain musical partners until an unfortunate and unsolvable disagreement in 1940. It was at the prompting of Jelly that the duo started to play in the war hospitals.

Charles Geoffroy-Decaume: Jelly d’Arány, ca 1920 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

After the war, Myra got a more powerful management company behind her, and her career started to improve immensely. By 1920, she was up to nearly 100 concerts a year (of recitals, charity performances, concertos, and chamber music), and 1921 saw three sold-out London performances.

1922, however, saw the most important improvement in Myra’s concert career: a coast-to-coast tour of the United States. The strength and vitality of an America untouched by the personal tragedies of WWI, which had left British orchestras stripped of so many players with in-country training falling far behind what was available in Europe. America was the goal of so many musicians from Russia and Europe that it rose to the top in the musical world. The contrast between the continuing mend-and-make-do mentality in England compared to the grand-scale solutions across the ocean made American tours, and American friends, better.

The reviews of her debut concert in New York, at Aeolian Hall, only had a small audience of 66, but brought brilliant reviews. The New York Tribune, Deems Taylor at The New York World, and Richard Aldrich in The New York Times all had unstinting praise for her musicality and their personal delight at what they heard.

In addition to an audience, Myra also discovered the piano that she would love most: the Steinway grand.

One of the works she would become most associated with, particularly as a concert encore, was her piano arrangement of the final chorale from Bach’s Cantata No. 147, Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring. Throughout the book, it is annoyingly referred to only as Jesu, Joy, as if it were a pop piece, but this reader suspects that was Hess’ own short form of the title, adopted by the author.

1954 BBC performance

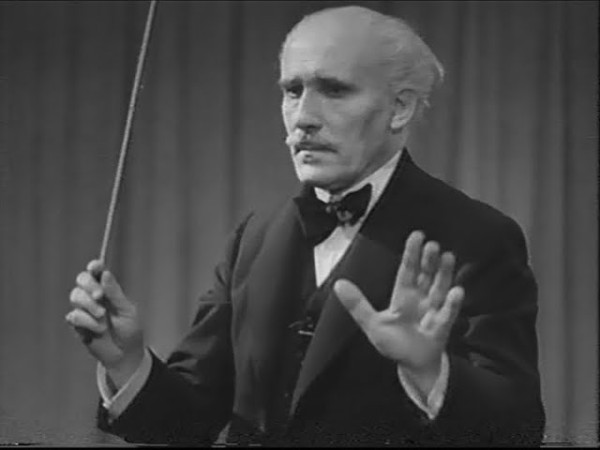

And that brings us to one of the other annoying things about the book. The constant use of nicknames for Myra’s entourage, made only more confusing when they change nicknames: if you miss the original reference, it’s difficult to discover who Maestro refers to (it’s Toscanini) when she worked with so many conductors and when her amanuensis Saz (i.e., Anita Gordon) turns to Swee but then still continues to be referred to as Saz, it all starts to get a bit mysterious.

Arturo Toscanini

While it makes the story very intimate and close to the subject, but when you stand back and attempt to see what happened when and who was there, it all can be a bit unclear.

Johannes Brahms: 4 Piano Pieces, Op. 119 – No. 3. Intermezzo in C Major (Myra Hess, piano)

Duchen’s life of Myra Hess is carefully placed into the societal norms that surrounded her and how her activism and feminism were important aspects of her life. When she took up the National Gallery concerts in 1939, it was with the encouragement of the director, Sir Kenneth Clark. He had closed the National Gallery and sent all the paintings away to points of safety in rural Britain, and lamented the ‘penitential ritual’ that the closing of cultural life represented. He pushed Myra from her original plan of one concert a week to a concert every day.

Of course, it turned out to be more than that. Concerts were held at 1 pm each weekday (lunchtime concerts) and repeat performances on Tuesdays and Thursdays (teatime concerts) for a total of 7 concerts a week. Price was 1 shilling at lunchtime and 2 shillings at teatime. All performers, amateur and professional alike, were paid a flat fee of 5 guineas (which would have been equal to 105 shillings), and any profits went to the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund, which by the end of the concert series was £16,000 (equal to 320,000 shillings) to the better. From those numbers, we can see the success of her Gallery concerts. From day 1 (Tuesday, 10 October 1939), just over a month after the start of WWII, the Gallery concerts were on their way. The expected 200 attendees for the first concert turned out to be 700–800, and hundreds of others had to be turned away.

The queue for a Gallery concert, ca 1939 (The National Gallery)

The opening program was two short sonatas by Scarlatti and two of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues, followed by Beethoven’s Appassionata, some of Schubert’s Dances, a Waltz and Nocturne by Chopin, the three Intermezzi from Opus 119 by Brahms, and finally Myra Hess’s famous arrangement of ‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring’.

Domenico Scarlatti: Keyboard Sonata in C Minor, K.11/L.352/P.67 (Myra Hess, piano)

Attendees included servicemen and women, and Queen Elizabeth, who was helpful in donating chairs from Buckingham Palace when the available supply in the city ran out.

On 10 April 1946, exactly six and a half years from their beginning, and after 1,698 concerts, the series came to a close. The pictures had come back to the Gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark had retired, and his successor wasn’t a fan of continuing music in his art space. Over time, 824,152 people had attended, and more than 700 musicians performed.

Her career resumed its upward path – more accolades from abroad and a rather cool reception at home were to be her fate for many more years. Finally, at the end, as her health took a toll on her ability to play, she retired after a vascular blockage left the motor nerves on the left side of her body in spasms. Complete paralysis was avoided, fortunately.

Robert Schumann: Etudes symphoniques (Symphonic Etudes), Op. 13 – Thema: Andante (Myra Hess, piano)

Public news stories laid the blame on rheumatism in her hands, which had been a problem for many years, but in the few concerts after that, her playing lacked control and couldn’t be recorded or broadcast. It was her entourage who had to break the news to her – her tempos were unsteady, and the number of wrong notes was growing. Finally, on 2 April 1962, the formal announcement was made of her cancellation of all engagements. She continued teaching but with reduced energy. She died on 25 November 1965.

At the end of the book are three pieces written by her students describing their time with her. Stephen Kovacevich, considered her leading pupil, writes about his choice between studying at Juilliard or studying in London with Myra Hess. He chose the latter. Anne Schein was another student who started with coaching from Rubinstein and then, concurrently, coaching with Myra; the two virtuosos had no problem with a shared student. Richard Contiguglia, who performed as a piano duo with his twin brother John, was one of her last students. I think it’s of note that all three of her students were Americans – she took few students, and none seem to have been British. Each student describes what they learned from her, and it’s a valuable addition to Myra’s life story.

The story has some wonderful details, and one of the funniest is about the location of her house in St John’s Wood, next door to Lord’s Cricket Ground: ‘I have never had applause when I practise. So now, when I am at the piano and hear people outside clapping their hands, I shall get up from the piano stool, go to the window and take a bow.’

Duchen tells the story well, although in a journalistic style that requires some getting used to. She writes about music and Myra’s development of her musical and social sides in a way that keeps the reader moving forward. Myra Hess was a remarkable musician, both for her advocacy of clarity of performance and her belief in the music, as well as for her support of women performers.

Myra Hess: National Treasure

Jessice Duchen

Amersham, Bucks: Kahn & Averill, 2025

1-978-0687762-0-5

424 pages

£40.00

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter